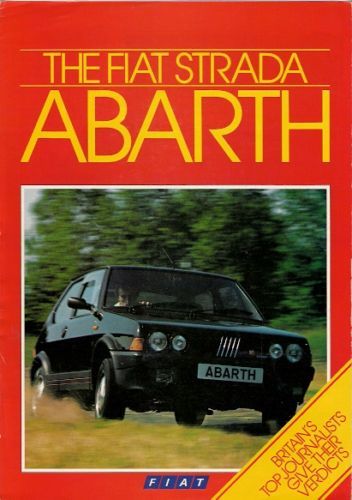

ABARTH Turino Italy 1949 till now II

Only the pictures from my Collection:

That’s all folks

That’s all folks

| Industry | Automotive |

|---|---|

| Fate | Bankrupt |

| Founded | 1946 |

| Defunct | 1963 |

| Headquarters | Turin, Italy |

|

Key people

|

Piero Dusio, founder |

| Products | Automobiles |

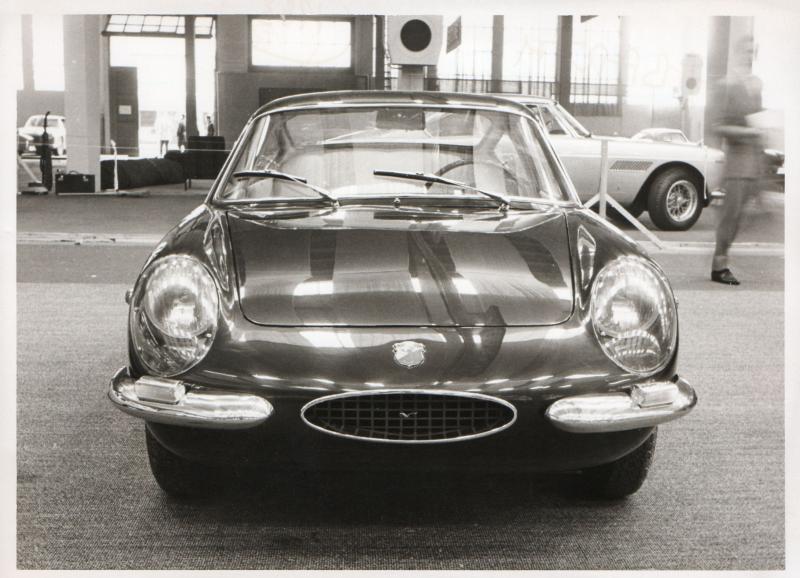

Cisitalia was an Italian sports and racing car brand. The name “Cisitalia” derives from “Compagnia Industriale Sportiva Italia”, a business conglomerate founded in Turin in 1946 and controlled by the wealthy industrialist and sportsman Piero Dusio. The Cisitalia 202 GT of 1946 is well known in the world as a “rolling sculpture”.

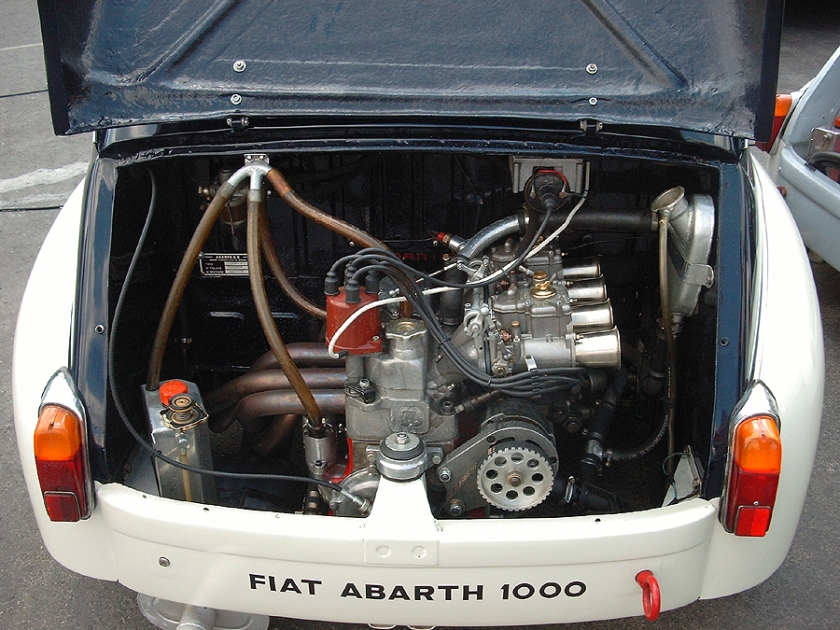

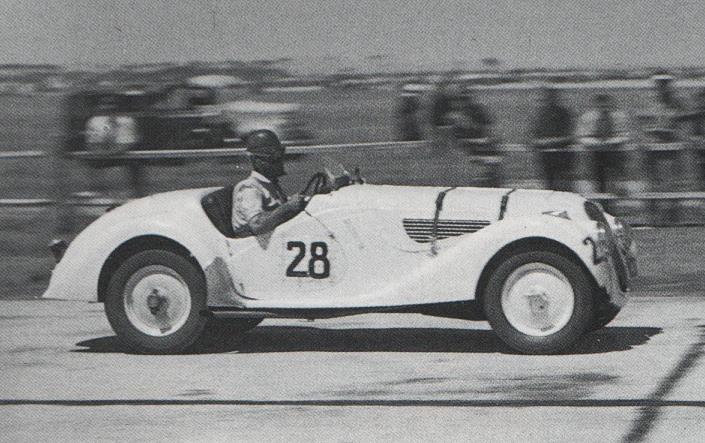

Using Fiat parts as a base Dante Giacosa designed the D46 which made its successful debut in 1946. Giacosa had a vast knowledge of Fiat bits and pieces as he had designed the legendary 500 Fiat Topolino before WW II. The engine and suspension were directly derived from the small Fiat but extensively modified for racing. The engine received dry sump lubrication and further tweaks considerably increased the power output to 60-70 bhp. With a spaceframe chassis and weighing under 400 kg (880 lb) the available power was more than enough for competitive performance. Dusio’s dream of a one model series came to nothing, but instead his D46s started to dominate the voiturette series. Highly talented drivers like Tazio Nuvolari piloted the D46 to multiple successes against more advanced but older racing cars.

This successes led to a much more ambitious single seater project that would prove too much for the small company. Ferdinand Porsche was commissioned to design and construct a full Grand Prix car which led to the innovative but complex Cisitalia 360. With a mid engined layout and four wheel drive the Type 360 was far too expensive for Dusio to support and the attempt essentially killed any further racing cars.

Dusio commissioned several automobiles from Europe’s leading designers. He provided Pinin Farina with the chassis, on which an aluminum body was handcrafted. When first presented to the public at the Villa d’Este Gold Cup show in Como, Italy, and at the 1947 Paris Motor Show, the two-seat 202GT was a resounding success. The 202 was an aesthetic and technical achievement that transformed postwar automobile body design. The Pinin Farina design was honored by New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1951. In the MOMA’s first exhibit on automotive design, called “Eight Automobiles”, the Cisitalia was displayed with seven other cars (1930 Mercedes-Benz SS tourer, 1939 Bentley saloon with coachwork by James Young, 1939 Talbot-Lago Figoni teardrop coupé, 1951 Willys Jeep, 1937 Cord 812 Custom Beverly Sedan, 1948 MG TC, and the 1941 Lincoln Continental coupe). It is still part of the MoMA permanent collection. It was not, however, a commercial success; because it was coachbuilt, it was expensive, and only 170 were produced between 1947 and 1952. Most cars were coachbuilt by Pinin Farina with some by Vignale and Stabilimenti Farina.

Building on aerodynamic studies developed for racing cars, the Cisitalia offers one of the most accomplished examples of coachwork conceived as a single shell. The hood, body, fenders, and headlights are integral to the continuously flowing surface, rather than added on. Before the Cisitalia, the prevailing approach followed by automobile designers when defining a volume and shaping the shell was to treat each part of the body as a separate, distinct element—a box to house the passengers, another for the motor, and headlights as appendages. In the Cisitalia, there are no sharp edges. Swellings and depressions maintain the overall flow and unity, creating a sense of speed.

The 202 is featured in the 2011 video game L.A. Noire by Rockstar Games and Team Bondi as a secret car called the Cisitalia Coupe.

Since the 202 never made large scale production and all the cars were handmade, the small talented group at Cisitalia, including Carlo Abarth, Dante Giacosa and Giovanni Savonuzzi, made several variants of the 202. Of the more important versions, the SMM Nuvolari Spider was built and named after a class victory at the 1947 Mille Miglia. It is easily identified by its large rear fins, twin windscreens and usual Italian blood red paint scheme.

Partly due to expensive construction of the mid-engine, four wheel drive formula one car, designed by Ferdinand Porsche. In total, around 200 cars were made which made a large impact on the later marques, including Abarth‘s later range of cars.

For the upcoming 1947 season, Giovanni Savonuzzi, who had designed most of the 202, sketched a coupe body for Cisitalia’s competition car. The design was executed by Stabilimenti Farina upon both chassis #101 and #102. After two coupes had been finished, a spider version, Called the SMM for Spider Mille Miglia, was completed which would adorn all subsequent competition cars bearing the MM designation.

At the 1947 Mille Miglia, the Cistitalia spider really proved itself by leading most of the race in capable hands of Tazio Nuvolari. Despite having competition with engines three times larger, Nuvolari held back the competition until troubles ensued in the rain. In the end, the Cistitalia took second overall and first in class. For this epic effort, subsequent competition spiders were known as 202 SMM Nuvolaris.

Since the 202 SMM received much attention at the Mille Miglia, Stabilimenti Farina continued production of the design for several customers. In total around 20 cars were made very similar to Nuvolari’s winning car.

(key) (results in bold indicate pole position; results in italics indicate fastest lap)

202C Cabriolet

202D Coupe and Spyder

303 DF Spyder

505DF

1953-cisitalia-voloradente-tipo33df

1955-cisitalia-202-cassone

Cisitalia 202 de Pininfarina

Cisitalia 202 Streamliner

Cisitalia 202 C Coupé

Cisitalia 202D

Cisitalia 202SC

Cisitalia 202SMM Spyder Nuvolari

Cisitalia 204 Spyder Sport

Cisitalia 303 Spyder

Cisitalia 360-Porsche 360 Grand Prix

Cisitalia 505 DF

Cisitalia 750GT

Cisitalia 808XF

Cisitalia Aerodinamica

Cisitalia D46-47-48 Monoposto Cisitalia Giacosa

cisitalia-166

cisitalia-202-si

That’s all

|

|

| Società per Azioni | |

| Industry | Automotive |

| Founded | Bologna, Italy (March 31, 1949) |

| Founder | Carlo Abarth |

| Headquarters | Turin, Italy |

|

Area served

|

EMEA |

|

Key people

|

|

| Parent | FCA Italy S.p.A. |

| Website | www.abarth.it |

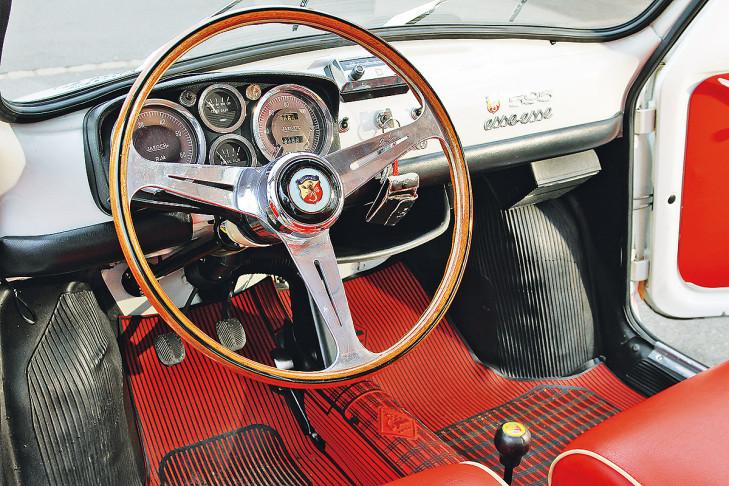

Abarth & C. S.p.A. is a racing car and road car maker founded by Carlo Abarth in 1949. Its logo is a shield with a stylized scorpion on a red and yellow background. Abarth & C. S.p.A. is a fully owned subsidiary of FCA Italy S.p.A. (formerly Fiat Group Automobiles S.p.A.), the subsidiary of Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (formerly of Fiat S.p.A.) controlling its European automotive production activities.

http://abarthcarsuk.com/about-abarth/the-history-of-abarth/

http://www.abarthisti.co.uk/abarth-history/

Carlo Abarth had been sporting director of the Cisitalia factory racing team since 1947. In 1948 begun the financial downfall of Cisitalia, spurred by the investments needed to put the 202 coupé into production; the following year the manufacturer went under, and founder Piero Dusio flew to Argentina. Carlo Abarth, funded by Armando Scagliarini, took over Cisitalia’s assets and on 31 March 1949 Abarth & C. was founded in Bologna. Carlo’s astrological sign, Scorpio, was chosen as the company logo. From the Cisitalia liquidation Abarth obtained five 204 sports cars (two complete Spiders and three unfinished), a D46 single seater and various spares. The 204s were immediately rechristened Abarth 204 A. Abarth built and raced sports cars developed from the last

Cisitalia cars.

Cisitalia cars.

In addition to Guido Scagliarini, the «Squadra Abarth» racing team lined up celebrated drivers such as Tazio Nuvolari, Franco Cortese and Piero Taruffi. Notably Tazio Nuvolari made his last appearance in racing at the wheel of an Abarth 204 A, winning is class in the Palermo–Monte pellegrino hillclimb on 10 April 1950. Alongside racing, the company main activity was producing and selling accessories and performance parts for Fiat, Lancia, Cisitalia and Simca cars, like inlet manifolds and silencers.

On April 9, 1951 the company’s headquarters were moved to Turin; Abarth began his well-known association with Fiat in 1952, when it built the

Abarth 1500 Biposto on Fiat mechanicals.

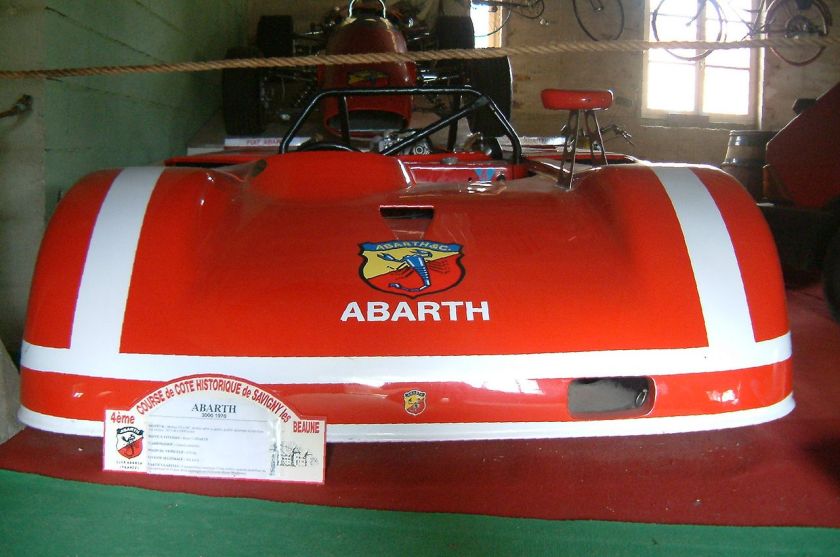

In the 1960s, Abarth was successful in hillclimbing and sports car racing, mainly in classes from 850cc to 2000cc, competing with Porsche 904 and Ferrari Dino. Hans Herrmann was a factory driver from 1962 until 1965, winning the 500 km Nürburgring in 1963 with Teddy Pilette.

Abarth promised Johann Abt that he could race a factory car for free if he won all the races he entered. Abt almost succeeded: Of the 30 races he entered, Abt won 29 and finished second once. Abt later founded Abt Sportsline.

Abarth produced high-performance exhaust pipes, diversifying into tuning kits for road vehicles, mainly for Fiat. A racing exhaust was produced for the 1950s Lambretta models “D” and “LD”. Original Abarth LD exhausts are now valuable collectors items. Reproductions are available which carry the Abarth name, how Fiat feels about this is not known. Lambretta even held several 125cc Motorcycle land speed records during the 1950s thanks partly to the exhaust that Abarth developed for them.

Abarth also helped build sports or racing cars with Porsche and Simca.

Carlo sold Abarth to Fiat on 31 July 1971. The acquisition was only made public by Fiat with a press release on 15 October. As Fiat was not interested in the Reparto Corse racing operations, these were taken over by Enzo Osella. Osella obtained cars, spares, technicians and drivers (amongst them Arturo Merzario), and continued the racing activity founding the Osella racing team. Thus ended for Abarth the days of sport prototype and hill climb racing.

Under Fiat ownership, Abarth became the Fiat Group’s racing department, managed by engine designer Aurelio Lampredi. Abarth prepared Fiat’s rally cars, including the

and 131 Abarth.

In December 1977, in advance of the 1978 racing season, the beforehand competing Abarth and Squadra Corse Lancia factory racing operations were merged by Fiat into a single entity named EASA (Ente per l’Attività Sportiva Automobilistica, Organization for Car Sports Racing Activities). Cesare Fiorio (previously in charge of the Lancia rally team) was appointed director, while Daniele Audetto was sporting director; the EASA headquarters were set up in Abarth’s Corso Marche (Turin) offices. The combined racing department developed the

Group 5 Lancia Montecarlo Turbo

Lancia Beta Montecarlo Turbo Group 5 racing car (1980 and 1981 World Sportscar Championship winner) and the Lancia Rally 037 Group B rally car (which won for Lancia the 1983 World Manufacturers’ Championship).

On 1 October 1981, Abarth & C. ceased to exist and was replaced by Fiat Auto Gestione Sportiva, a division of the parent company specialized in the management of racing programmes that would remain in operation through to the end of 1999, when it changed toFiat Auto Corse S.p.A.

Some commercial models built by Fiat or its subsidiaries Lancia and Autobianchi were co-branded Abarth, including the

Autobianchi A112 Abarth, a popular “boy racer” because it was lightweight and inexpensive.

In the 1980s Abarth name was mainly used to mark performance cars, such as the Fiat Ritmo Abarth 125/130 TC.

In 2000s, Fiat used the Abarth brand to designate a trim/model level, as in the Fiat Stilo Abarth.

On 1 February 2007 Abarth was re-established as an independent unit with the launch of the current company, Abarth & C. S.p.a., controlled 100% by Fiat Group Automobiles S.p.A., the subsidiary of Fiat S.p.A. dealing with the production and selling of passenger cars and light commercial vehicles. The first model launched was the Abarth Grande Punto and the Abarth Grande Punto S2000. The brand is based in the Officine 83, part of the old Mirafiori engineering plant. The CEO is Harald Wester.

In 2015 Abarth’s parent company was renamed FCA Italy S.p.A., reflecting the incorporation of Fiat S.p.A. into Fiat Chrysler Automobiles that took place in the previous months.

2007-10 Abarth Grande Punto Essesse

Supermini + 3-door hatchback

Abarth 500

City car + 3-door hatchback

Abarth 500C

City car + Cabriolet

Fiat Abarth 750

Abarth 209A Boano Coupe

Abarth 209A Boano Coupe

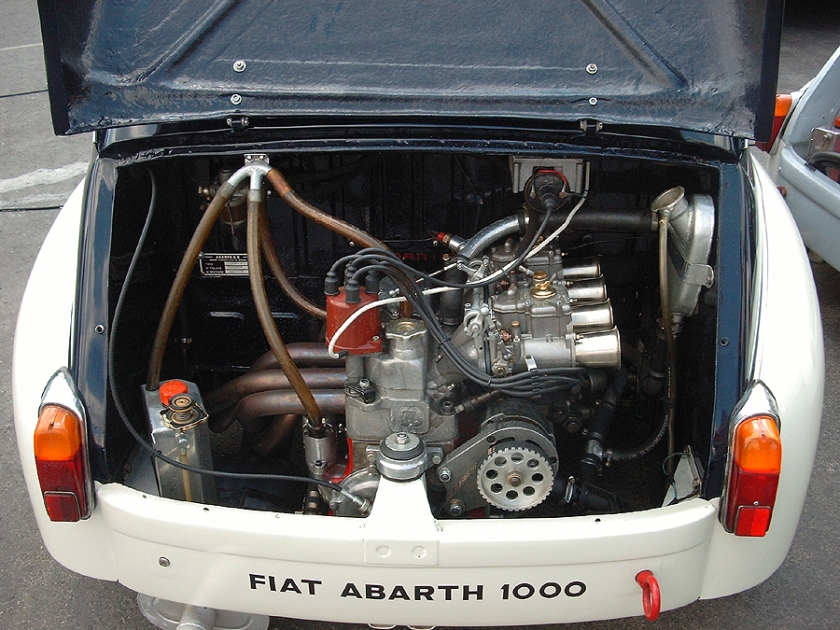

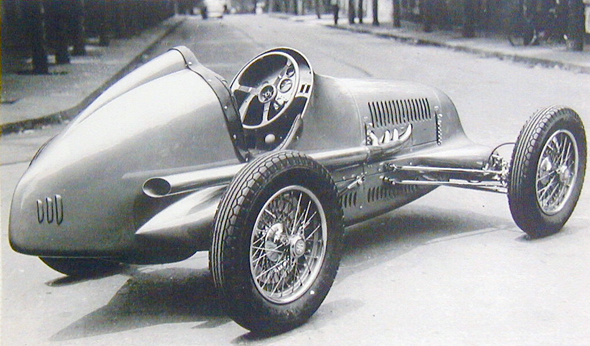

Fiat-Abarth 1000 TC (Fiat 600 based)

Fiat-Abarth 1000 TC (Fiat 600 based)1963 Abarth Simca 2000 – coupé

1955 Abarth 207A Spyder

1955 Abarth 207A Spyder

Porsche 356B Carrera GTL Abarth

Porsche 356B Carrera GTL Abarth

1964 Fiat-Abarth OT1000

1964 Fiat-Abarth OT1000

1964 Fiat-Abarth OT1600

1964 Fiat-Abarth OT1600

1966 Fiat-Abarth OT 2000 Competition Coupé

1966 Fiat-Abarth OT 2000 Competition Coupé

1959-64 Fiat-Abarth 2200

1959-64 Fiat-Abarth 2200

Fiat-Abarth Allemano 750 Spider

Fiat-Abarth Allemano 750 Spider

1963 Fiat-Abarth 595 SS

1963 Fiat-Abarth 595 SS

1965-68 Abarth OT 1300

1965-68 Abarth OT 1300

1961-65 Abarth Monomille

1961-65 Abarth Monomille

1968-71 Abarth Grand Prix/Scorpione

1968-71 Abarth Grand Prix/Scorpione

1969-71 Abarth 3000 Prototipo

1969-71 Abarth 3000 Prototipo

1981-88 Fiat Ritmo 125/130 TC Abarth

1981-88 Fiat Ritmo 125/130 TC Abarth

1985 Lancia 037

1985 Lancia 037

Lancia Abarth Kappa Coupe Turbo

Lancia Abarth Kappa Coupe Turbo

1999-01 Fiat Bravo GT/HGT (Abarth)

1999-01 Fiat Bravo GT/HGT (Abarth)

2007 Fiat Bravo Type 198 (Abarth)

2007 Fiat Bravo Type 198 (Abarth)

2002-09 Fiat Stilo (Abarth)

2002-09 Fiat Stilo (Abarth)

Fiat Cinquecento Sporting (Abarth)

Fiat Cinquecento Sporting (Abarth)

Fiat Seicento Sporting (Abarth)

Fiat Seicento Sporting (Abarth)

2009 Assetto Corsa Rally

Abarth Punto Supersport (2012–2013)

Abarth Punto Supersport (2012–2013)

Lancia Delta S4 for Group B – Helped to engineer the engine which utilised a supercharger and turbocharger.

Fiat Punto Abarth (rally version only)

Fiat Punto Abarth (rally version only)

Fiat Cinquecento 900 Trofeo kitcar (teams had to build up their own rallycar from Fiat N Technology derived Abarth racingparts)

Fiat Cinquecento 900 Trofeo kitcar (teams had to build up their own rallycar from Fiat N Technology derived Abarth racingparts)

The Imperia-Abadal model was manufactured by Imperia under Abadal license

The Abadal was a Spanish car manufactured between 1912 and 1923, named after Francisco Abadal. Considered a fast luxury car, it was closely patterned on the Hispano Carrocera and offered in two models. One had a 3104 cc four-cylinder engine while the other had a 4521 cc six-cylinder engine.

Soon after the inception of the Abadal line, the Belgian company Impéria began building Abadals under license as Impéria-Abadals. In 1916 Abadal acquired the Buick agency, and Barcelona-built Abadals after that year had Buick power units and featured custom coachwork. These cars were called “Abadal-Buicks”. M. A. Van Roggen (formerly of Springuel) took over the Belgian operation soon after, and built around 170 more Impéria-Abadals. Among the models produced were a 2992cc 16-valve four-cylinder OHC sports model and three prototype 5630 cc straight-eights. The company ceased automobile production in 1923.

Francisco Abadal (nicknamed Paco) was a Hispano-Suiza salesman and racing driver in Barcelona. He began this enterprise in 1912, and upon its cessation became an agent of General Motors in Spain. General Motors’ plans in 1930 related to a prototype named the Abadal Continental never materialised.

Abadal also produced the Abadal Y-12 aero-engine. a multiple bank in-line engine with twelve cylinders in three banks of four arranged in a Y.

1908 Abadal chassis

| Auto Avio Costruzioni 815 | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | Auto Avio Costruzioni |

| Production | 1940 2 produced |

| Assembly | Modena, Italy |

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Sports car |

| Body style | 2-seat barchetta |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | 1.5 L (1496 cc) SOHC I8 |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 2,420 mm (95.3 in) |

| Curb weight | 625 kg (1,378 lb) |

| Chronology | |

| Successor | Ferrari 125 S |

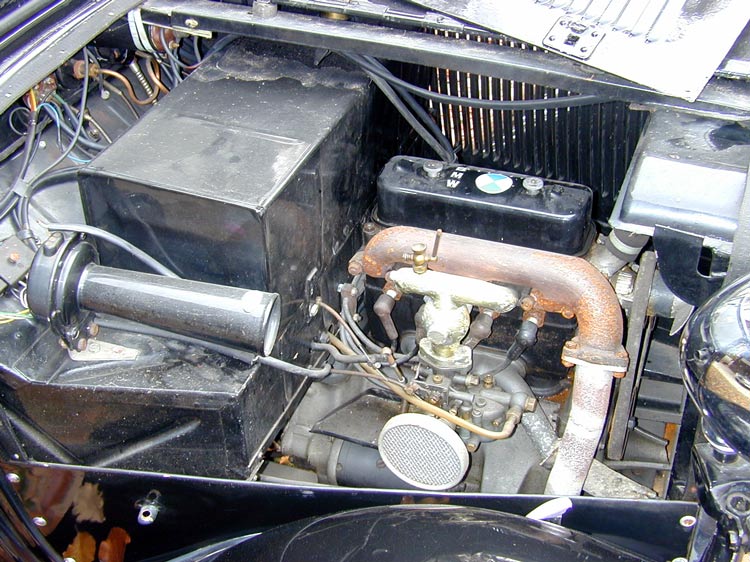

The Auto Avio Costruzioni 815 was the first car to be fully designed and built by Enzo Ferrari. Legal issues with former associates Alfa Romeo prevented Ferrari from creating the Ferrari marque. The 815 raced at the 1940 Brescia Grand Prix, where both entries failed to finish due to engine problems. One of the cars was later scrapped, while the other is currently in a car collection in Italy.

In 1938, Ferrari left Alfa Romeo after running Scuderia Ferrari as their racing division. The agreement ending their association forbade Ferrari from restarting Scuderia Ferrari within the next four years. Ferrari then founded Auto Avio Costruzioni (AAC) in Modena to manufacture aircraft parts for the Italian government

In December 1939, AAC was commissioned by Lotario, Marquis di Modena, to build and prepare two racing cars for him and Alberto Ascari to drive in the 1940 Brescia Grand Prix. The race, a successor to the Mille Miglia, was to be run in April 1940. The resulting car was named the AAC Tipo 815.

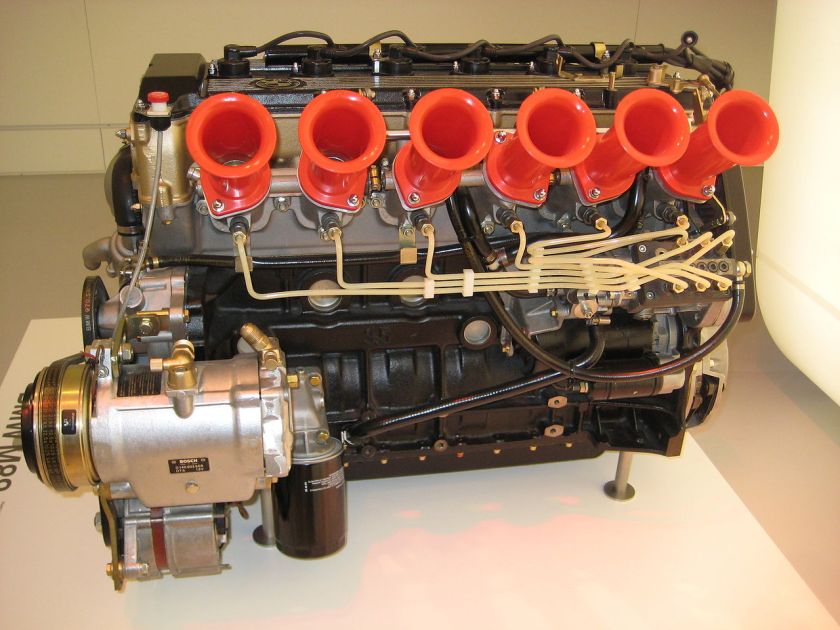

The 815 was designed and developed by ex-Alfa Romeo engineers Alberto Massimino and Vittorio Bellentani and by Enrico Nardi. The designation “815” was based on the car’s eight-cylinder, 1.5 L engine. This engine was largely based on the four-cylinder, 1.1 L engine of the 508 C Balilla 1100. In concept, it was two 508C engines placed end to end, but it used a specially designed aluminium block built by Fonderia Calzoni in Bologna for integrity and light weight and a five-bearing crankshaft and a camshaft designed and built by AAC to get the traditional straight-8 timing and balance. The engine used Fiat valve gear, cylinder heads (two 508C heads per engine), and connecting rods. The engine was high-tech for the time, with a single overhead camshaft, two valves per cylinder, and a semi-dry sump lubrication system. Four Weber 30DR2 carburettors were specified for a total output of 75 hp (56 kW) at 5500 rpm.

The 815 used a Fiat four-speed transmission with the Fiat gears replaced by gears made in-house by AAC. The transmission was integral to the engine block. The car had independent Dubonnet suspension with integral shock absorber at front, with a live axle on semi-elliptic leaf springs and hydraulic shock absorbers at the rear.

The bodywork was done by Carrozzeria Touring using Itallumag 35, an aluminium/magnesium alloy, and was done in long, flowing forms with integrated wings.[3] The bodywork weighed 119 lb (54 kg). The complete car weighed 625 kg (1,378 lb) and attained a maximum speed close to 170 km/h (110 mph).

Two 815s, numbers 020 and 021, were completed and entered in the 1940 Brescia Grand Prix, which ran nine laps of a 103 miles (166 km) street circuit. Rangoni and Nardi raced in 020, while Ascari and Giuseppe Minozzi raced in 021. After leading the 1500 cc class in the first lap, Ascari’s car developed valve problems and broke down. Rangoni then took the lead, set the lap record for the class, and had a lead of more than half an hour when his engine failed after seven laps.

Lotario Rangoni died during the Second World War and his brother, Rolando, inherited car no. 020. The car was scrapped in 1958.

Ascari’s car, no. 021, was sold to racer Enrico Beltracchini who raced it in 1947. After selling the car to a museum and then buying it back, Beltracchini sold it again to Mario Righini. As at 2006, Type 815 no. 021 was still in Righini’s collection.

Auto Avio Costruzioni 815

AAC tipo 815 at the Panzano Castle 2009

Fiat-based engine in the AAC tipo 815.

https://www.classicdriver.com/en/article/cars/auto-avio-costruzioni-815-secret-first-ferrari

http://www.topspeed.com/cars/ferrari/1940-ferrari-auto-avio-costruzioni-815-ar78772.html

|

|

|---|

A barchetta (Italian pronunciation: [barˈketta], “little boat” in Italian) was originally an Italian style of open 2-seater sports car which was built for racing. Weight and wind resistance were kept to a minimum, and any unnecessary equipment or decoration were sacrificed in order to maximize performance.

Although most barchettas were made from the late 1940s through the 1950s, the style has occasionally been revived by small-volume manufacturers and specialist builders in recent years.

Typically handmade in aluminium on a tubular frame, the classic barchetta body is devoid of bumpers or any weather equipment such as a canvas top or sidescreens, and has no provision for luggage. Some barchettas have no windscreen; others, a shallow racing-type screen or aero screen(s).

The classic barchetta either had no doors, in which case entry and exit entailed stepping over the side of the car, or very small doors without exterior handles.

Giovanni Canestrini, when editor of La Gazzetta dello Sport, a popular Italian sporting newspaper, was the first to use the term “barchetta” on a car, using it to describe the new Ferrari 166MM displayed at the 1948 Turin Auto Show. The name has been associated with the model ever since.

The MM in the car’s designation stood for Mille Miglia, the race it won in 1948 and 1949. In 1949 the 166MM barchetta also won the 24 Hours of Le Mans (driven by Luigi Chinetti and Lord Selsdon) and the Targa Florio (with Clemente Biondetti and Igor Troubetzkoy), the only car ever to win all three races in the same year. It also won the 1949 Spa 24 Hours. The car’s unadorned, lightweight aluminium body was designed by Carrozzeria Touring’s head of design, Carlo Felice Bianchi Anderloni.

Motor Trend Classic rated the 166MM barchetta sixth out of the ten “greatest Ferraris of all time”.

The OSCA MT4, a 1452 cc, 130 bhp (97 kW) barchetta made by the Maserati brothers, was for eight years the most successful under-1500 cc sports racing car in the world.

Other, even more diminutive OSCA barchettas were powered by engines of 750 cc and 850 cc.

Giovanni Moretti, another designer and manufacturer, also made several small barchettas in the 1950s.

The 1966 Abarth 1000SP barchetta was a successful race car, and in 2007 the car design firm Carrozzeria Bertone celebrated its 95th anniversary with the Fiat Panda-based Fiat Barchetta Bertone, an “open-topped strictly two-seater sports car that calls to mind the Italian racing cars of the 1950s. In this case, the design explicitly cites the Fiat 500 with the barchetta bodywork created by the young Nuccio Bertone in 1947 as a one-off for his personal use in races […and] projects the concept of the barchetta, a historic icon in the legend of Italian motorsports, into the future with purposeful elegance and sophisticated irony.”

Ferrari revived the name in 2001 for their 550 Pininfarina Barchetta, which marked Pininfarina’s 70th anniversary. The car was first shown at the 2001 Salon de l’Automobile and 448 examples were built. It is “[i]n many ways…the legitimate successor to such legendary open Ferraris as the 166MM…” Designed as a roadster for use on public roads and not as a full-bred racing car, the 550 Barchetta has a rudimentary convertible top “whose mechanism is said to require strength, skill, and patience.” The top is intended only for emergency use in a sudden downpour and the manufacturer advises against using it at speeds above 70 miles per hour (110 km/h). The top “doesn’t look as if it would survive the sacrilege of an automatic carwash.” The list price of the 550 Barchetta was $245,000.

The 1995-97 Renault Spider, although mid-engined, was designed very much in the barchetta style, and also in the barchetta tradition, as it was intended for racing. Renault sponsored a one-make race series for it. Although the Spider is road-legal it has no weather protection, and drivers of first-series Spiders usually wear a helmet on the road as these early models were sold without the windscreen that came with the later models.

Despite its name, the 1995-2005 Fiat Barchetta was not a sports car in the barchetta style or tradition.

1947 A.L.C.A. Volpe

http://myntransportblog.com/2015/01/17/alca-volpe-aero-caproni-trento-milan-italy/

1947 A.L.C.A. Volpe Aero Caproni, Trento ITALY 125 cc

ALCA means:

Introduced in Italy as an even *smaller* alternative to the Fiat 500, the Volpe (fox) was met with much enthusiasm by the Italian Press.

Pre-production models had engines installed but apparently these were for display purposes only. Problems with suppliers caused problems with customers.

Despite many pre-orders and pre-payments no completed Volpes were apparently delivered.

The car was also pre-sold and marketed in Spain as the Hispano-Volpe.

Reports of an actual running Volpe being delivered to the USA in 1951 were probably the result of someone obtaining an incomplete model of the car and fitting their own motor to it. Also- a surprisingly identical car emerged briefly in 1951 called the Parvus Fox. Coincidence?

While expected to have a 125cc motor, none were probably installed and this car stays true to theVolpe as it was manufactured: It also has No Motor.

Manufacturer: Aero Caproni, Trento ITALY

| Model: Volpe | Motor: none! | Body : Steel |

| Years Built: 1947 | No. Cylinders: n/a | Chassis: Steel Tube |

| No. Produced: ~10 maybe | Displacement: 125 cc (alledged) | Suspension Front: Leaf Spring |

| No. Surviving: ~1 or 2 | Horsepower: 9 (alledged) | Suspension Rear: Leaf Spring |

| Length: 2500 mm | Gearbox: n/a | Steering: Worm gear |

| Width: 1220 mm | Starter: n/a | Brakes: Cable |

| Weight: 15 kg | Electrics: n/a | 4 Wheels: 4.00 x 8″ |

| Interior: Bench | Ignition: n/a | Top Speed: 60 km/h (claimed) |

| Sunbeam Alpine | |

|---|---|

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | Sunbeam (Rootes Group) |

| Production | 1953–75 |

| Assembly | Ryton-on-Dunsmore, Warwickshire, England |

| Body and chassis | |

| Body style | Sports car |

| Layout | FR layout |

The Sunbeam Alpine is a sporty two-seat open car produced by Sunbeam from 1953 to 1955, and then 1959 to 1968. The name was then used on a two-door fastback from 1969 to 1975. The original Alpine was launched in 1953 as the first vehicle from Sunbeam-Talbot to bear the Sunbeam name alone since the 1935 takeover of Sunbeam and Talbot by the Rootes Group.

| Sunbeam Alpine Mark I & III | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Overview | |

| Production | 1953–55 1.582 made |

| Assembly | United Kingdom Australia |

| Body and chassis | |

| Body style | 2-door roadster |

| Related | Sunbeam-Talbot 90 |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | 2267 cc (2.3L) I4 |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 97.5 in (2,476 mm) |

| Length | 168.5 in (4,280 mm) |

| Width | 62.5 in (1,588 mm) |

| Chronology | |

| Successor | Series Alpine |

The Alpine was derived from the Sunbeam-Talbot 90 Saloon,

and has become colloquially known as the “Talbot” Alpine. It was a two-seater sports roadster initially developed by Sunbeam-Talbot dealer George Hartwell in Bournemouth, as a one-off rally car. It had its beginnings as a 1952 Sunbeam-Talbot drophead coupé, and was supposedly named by Norman Garrad of the works Competition Department, who was heavily involved in Sunbeam-Talbot’s successes in the Alpine Rally during the early 1950s using the saloon models.

The car has a four-cylinder 2267 cc engine from the saloon, but with a raised compression ratio. However, since it was developed from the saloon platform, it suffered from rigidity compromises despite extra side members in the chassis. The gearbox ratios were changed, and from 1954 an overdrive unit became standard. The gearchange lever was column-mounted.

The Alpine Mark I and Mark III (no Mark II was made) were hand-built – as was the 90 drophead coupé – at Thrupp & Maberly coachbuilders from 1953 to 1955, and remained in production for only two years. Of the 1582 automobiles produced, 961 were exported to the USA and Canada, 445 stayed in the UK, and 175 went to other world markets. It has been estimated that perhaps as few as 200 have survived.

1954 Sunbeam Alpine Mk1 Two seater

The Sunbeam Alpine Mk 1 Special: It was based on the 2267cc Mk 1 Sunbeam Talbot motor, with alloy rocker cover and Siamese exhaust ports [ cylinders 2 and 3 ]. These motors developed a reputed, 97.5 bhp at 4,500 rpm, mainly by raising the compression ratio to 8.0:1 and incorporating a special induction manifold with a twin choke Solex 40 P.I.I carburettor .

Sunbeam Alpine Team Cars : MKV 21 – 26: The motors were configured the same as the Sunbeam Alpine Mk I Special, with further tuning by ERA to raise power to over 100 bhp.

In the 1953 Alpine Rally four Alpines won the Coupe des Alpes, one of which, finishing 6th, was driven by Stirling Moss; Sheila van Damm won the Coupe Des Dames in the same rally.

Very few of these cars are ever seen on the big screen. However, a sapphire blue Alpine featured prominently in the 1955 Alfred Hitchcock film To Catch a Thief starring Cary Grant and Grace Kelly. More recently, the American PBS show History Detectives tried to verify that an Alpine roadster owned by a private individual was the actual car used in that movie. Although the Technicolor process could “hide” the car’s true colour, and knowing that the car was shipped back from Monaco to the USA for use in front of a rear projection effect, the car shown on the programme was ultimately proven not to be the film car upon comparison of the vehicle identification numbers.

| Sunbeam Alpine Series I to V | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Overview | |

| Production | 1959–68 69,251 made |

| Body and chassis | |

| Body style | 2-door roadster |

| Related | Sunbeam Tiger |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | Series I: 91.2 cu in (1.5 L) I4 Series II, III & IV—1592 cc (1.6L) I4 Series V—1725 cc (1.7L) I4 |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 86 in (2,184 mm) |

| Length | 155 in (3,937 mm) |

| Width | 61 in (1,549 mm) |

| Height | 51 in (1,295 mm) |

| Chronology | |

| Successor | none |

Kenneth Howes and Jeff Crompton were tasked with doing a complete redesign in 1956, with the goal of producing a dedicated sports car aimed principally at the US market. Ken Howes contributed some 80 per cent of the overall design work, which bears more than incidental resemblance to the early Ford Thunderbird; Howe had worked at Ford before joining Rootes.

The Alpine was produced in four subsequent revisions until 1968. Total production numbered around 70,000. Production stopped shortly after the Chrysler takeover of the Rootes Group.

The “Series” Alpine started production in 1959. One of the original prototypes still survives and was raced by British Touring car champion Bernard Unett.

The car made extensive use of components from other Rootes Group vehicles and was built on a modified floorpan from the Hillman Husky estate car. The running gear came mainly from the Sunbeam Rapier, but with front disc brakes replacing the saloon car’s drums. An overdrive unit and wire wheels were optional. The suspension was independent at the front using coil springs and at the rear had a live axle and semi-elliptic springing. The Girling-manufactured brakes used 9.5 in (241 mm) discs at the front and 9 in (229 mm)drums at the rear.

Coupe versions of the post-1959 version were built by Thomas Harrington Ltd. Until 1962 the car was assembled for Rootes by Armstrong Siddeley.

An open car with overdrive was tested by the British magazine The Motor in 1959. It had a top speed of 99.5 mph (160.1 km/h) and could accelerate from 0–60 mph (97 km/h) in 13.6 seconds. A fuel consumption of 31.4 miles per imperial gallon (9.0 L/100 km; 26.1 mpg-US) was recorded. The test car cost £1031 including taxes.

11,904 examples of the series I were produced.

In 1960 Sunbeam marketed a limited-production three-door variant of the Alpine, marketed as a shooting brake. With leather interior and walnut trim, its price was double that of its open counterpart.

The Series I featured a 1494 cc engine and was styled by the Loewy Studios for the Rootes Group. It had dual downdraft carburetors, a soft top that could be hidden by special integral covers and the first available roll-up side windows offered in a British sports car of that time.

The Series II of 1962 featured an enlarged 1592 cc engine producing 80 bhp and revised rear suspension, but there were few other changes. When it was replaced in 1963, 19,956 had been made.

A Series II with hardtop and overdrive was tested by The Motor magazine in 1960, which recorded a top speed of 98.6 mph (158.7 km/h), acceleration from 0–60 mph (97 km/h) in 13.6 seconds and a fuel consumption of 31.0 miles per imperial gallon (9.1 L/100 km; 25.8 mpg-US). The test car cost £1,110 including taxes.

The Series III was produced in open and removable hardtop versions. On the hardtop version the top could be removed but no soft-top was provided as the area it would have been folded into was occupied by a small rear seat; also the 1592 cc engine was less powerful. To provide more room in the boot, twin fuel tanks in the rear wings were fitted. Quarter light were fitted to the windows. Between 1963 and 1964, 5863 were made.[9]

There was no longer a lower-output engine option; the convertible and hardtop versions shared the same 82 bhp engine with single Solex carburettor. A new rear styling was introduced with the fins largely removed. Automatic transmission with floor-mounted control became an option, but was unpopular. From autumn 1964 a new manual gearbox with synchromesh on first gear was adopted in line with its use in other Rootes cars. A total of 12,406 were made.

The final version had a new five-bearing 1725 cc engine with twin Zenith-Stromberg semi-downdraught carburettors producing 93 bhp. There was no longer an automatic transmission option. 19,122 were made. In some export markets, 100 PS (99 bhp) SAE were claimed.

1967 Sunbeam Alpine Series V

1967 Sunbeam Alpine Series V rear

A muscle-car variant of the later versions was also built, the

The Alpine enjoyed relative success in European and North American competition. Probably the most notable international success was at Le Mans, where a Sunbeam Harrington won the Thermal Index of Efficiency in 1961. In the United States the Alpine competed successfully in Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) events.

Vince Tamburo won the G-Production National Championship in 1960 using the 1494cc Series I Alpine. In 1961 Don Sesslar took 2nd in the F-Production National Championship followed by a 3rd in the Championship in 1962. For 1963 the Alpine was moved into E-Production facing stiff competition from a class dominated by the Porsche 356. Sesslar tied in points for the national championship while Norman Lamb won the Southwest Division Championship in his Alpine.

A championship for Don Sesslar finally was achieved in 1964 with 5 wins (the SCCA totaled the 5 top finishes for the year). Dan Carmichael won the Central Division Championship in 1964 and ’65. Carmichael continued to race the Alpine until 1967, when he finished 2nd at the American Road Race of Champions.

Bernard Unett raced factory prototype Alpine (registration number XRW 302) from 1962 to 1964 and in 1964 won the Fredy Dixon challenge trophy, which was considered to be biggest prize on the British club circuit at the time. Unett went on to become British Touring car champion three times during the 1970s.

A six-car works team was set up for the 1953 Alpine Rally. Although outwardly similar to their production-car counterparts they reputedly incorporated some 36 modifications, boosting the engine to an estimated 97.5 bhp.

| Sunbeam Alpine “Fastback” | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Overview | |

| Production | 1969–75 |

| Body and chassis | |

| Body style | 2-door fastback |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | 1725 cc (1.7L) I4 |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 98.5 in (2,502 mm) |

| Length | 174.5 in (4,432 mm) |

| Width | 64.75 in (1,645 mm) |

| Chronology | |

| Successor | none |

Rootes introduced the “Arrow” range in 1967, and by 1968 the saloons and estates (such as the Hillman Hunter) had been joined by a Sunbeam Rapier Fastback coupé model. In 1969, a cheaper, slightly slower and more economical version of the Rapier (still sold as a sporty model) was badged as the new Sunbeam Alpine.

All models featured the group’s strong five-bearing 1725 cc engine, with the Alpine featuring a single Stromberg CD150 carburettor to the Rapier’s twins, and the Rapier H120’s twin 40DCOE Weber carburettors.

Although drawing many parts from the group’s “parts bin”, including the rear lights of the estate Arrow models, the fastbacks nevertheless offered a number of unique features, including their pillar-less doors and rear side windows which combined to open up the car much like a cabriolet with a hardtop fitted. Extensive wooden dashboards were fitted to some models, and sports seats were available for a time.

The Alpine name was resurrected in 1976 by Chrysler (by then the owner of Rootes), on a totally unrelated vehicle that could not have been more different: the UK-market version of the Simca 1307, a French-built family hatchback. The car was initially badged as the Chrysler Alpine, and then finally as the Talbot Alpine following Chrysler Europe’s takeover by Peugeot in 1978. The name survived until 1984, although the design survived (with different names) until 1986.

|

|

Alpine factory, Dieppe

|

|

| Subsidiary | |

| Industry | Automotive |

| Founded | 1955 |

| Founder | Jean Rédélé |

| Defunct | 1995 |

| Headquarters | Dieppe, France |

| Products | Automobiles |

| Parent | Renault |

| Website | alpine-cars.com |

Alpine was a French manufacturer of racing and sports cars that used rear-mounted Renault engines.

Jean Rédélé, the founder of Alpine, was originally a Dieppe garage proprietor, who began to achieve considerable competition success in one of the few French cars produced just after the Second World War. The company was bought in 1973 by Renault.

Using Renault 4CVs, Rédélé gained class wins in a number of major events, including the Mille Miglia and Coupe des Alpes. As his experience with the little 4CV built up, he incorporated many modifications, including for example, special 5-speed gear boxes replacing the original 3-speed unit. To provide a lighter car he built a number of special versions with lightweight aluminium bodies: he drove in these at Le Mans and Sebring with some success in the early 1950s.

Encouraged by the development of these cars and consequent customer demand, he founded the Société Anonyme des Automobiles Alpine in 1954. The firm was named Alpine after his Coupe des Alpes successes. He did not realise that in England the previous year, Sunbeam had introduced a sports coupe derived from the Sunbeam Talbot and called the Sunbeam Alpine. This naming problem was to cause problems for Alpine throughout its history.

In 1955, he worked with the Chappe brothers to be amongst the pioneers of auto glass fibre construction and produced a small coupe, based on 4CV mechanicals and called the Alpine A106. It used the platform chassis of the original Renault 4CV. The A106 achieved a number of successes through the 1950s and was joined by a low and stylish cabriolet. Styling for this car was contracted to the Italian designer Giovanni Michelotti. Under the glassfibre body was a very stiff chassis based on a central tubular backbone which was to be the hallmark of all Alpines built.

Alpine then took the Michelotti cabriolet design and developed a 2+2 closed coupe (or ‘berlinette’) body for it: this became the Alpine A108, now featuring the Dauphine Gordini 845 cc engine, which on later models was bored out to give a capacity of 904 cc or (subsequently) 998 cc. The A108 was built between 1958 and 1963.

In 1962, the A108 began to be produced also in Brazil, by Willys-Overland. It was the Willys Interlagos (berlineta, coupé and convertible).

By now the car’s mechanicals were beginning to show their age in Europe. Alpine was already working closely with Renault and when the Renault R8 saloon was introduced in 1962. Alpine redeveloped their chassis and made a number of minor body changes to allow the use of R8 mechanicals.

This new car was the A110 Berlinette Tour de France, named after a successful run with the Alpine A108 in the 1962 event. Starting with a 956 cc engine of 51 bhp (38 kW), the same chassis and body developed with relatively minor changes over the years to the stage where, by 1974, the little car was handling 1800 cc engines developing 180 bhp (134 kW)+. With a competition weight for the car of around 620 kg (1,367 lb), the performance was excellent.

Alpine achieved increasing success in rallying, and by 1968 had been allocated the whole Renault competition budget. The close collaboration allowed Alpines to be sold and maintained in France by normal Renault dealerships. Real top level success started in 1968 with outright wins in the Coupe des Alpes and other international events. By this time the competition cars were fitted with 1440 cc engines derived from the Renault R8Gordini. Competition successes became numerous, helped since Alpine were the first company fully to exploit the competition parts homologation rules.

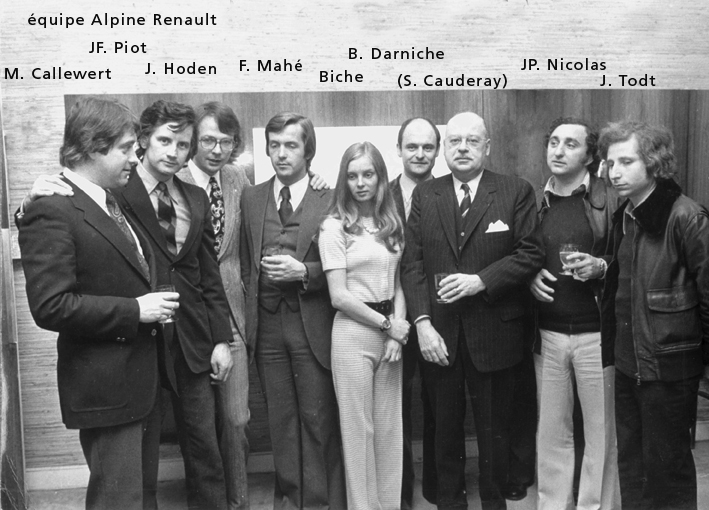

In 1971, Alpine achieved a 1-2-3 finish in the Monte Carlo rally, using cars with engines derived from the Renault 16. In 1973, they repeated the 1-2-3 Monte Carlo result and went on to win the World Rally Championship outright, beating Porsche, Lancia and Ford. During all of this time, production of the Alpine A110 increased and manufacturing deals were struck for A110s and A108s with factories in a number of other countries including Spain, Mexico, Brazil and Bulgaria.

1973 brought the international petrol crisis, which had profound effects on many specialist car manufacturers worldwide. From a total Alpine production of 1421 in 1972, the numbers of cars sold dropped to 957 in 1974 and the company was bailed out via a takeover by Renault. Alpine’s problems had been compounded by the need for them to develop a replacement for the A110 and launch the car just when European petrol prices leapt through the roof.

Through the 1970s, Alpine continued to campaign the A110, and later the Alpine A310 replacement car. However, to compete with Alpine’s success, other manufacturers developed increasingly special cars, notably the Lancia Stratos which was based closely on the A110’s size and rear-engined concept, though incorporating a Ferrari engine. Alpine’s own cars, still based on the 1962 design and using a surprising number of production parts, became increasingly uncompetitive. In 1974 Alpine built a series of factory racing Renault 17 Gordinis (one driven by Jean-Luc Thérier) that won the Press on Regardless World Rally Championship round in Michigan, USA.

In fact, having achieved the rally championship, and with Renault money now fully behind them, Alpine had set their sights on a new target. The next aim was to win at Le Mans. Renault had also taken over the Gordini tuning firm and merged the two to form Renault Sport. A number of increasingly successful sports racing cars appeared, culminating in the 1978 Le Mans win with the Renault Alpine A442B. This was fitted with a turbo-charged engine; Alpine had been the first company to run in and win an international rally with a turbo car as far back as 1972 when Jean-Luc Thérier took a specially modified A110 to victory on the Critérium des Cévennes.

1971 also saw Alpine begin construction of open wheel racing cars. Initially in Formula Three within a year they were building Formula Two cars as well. Unfortunately without a competitive Renault Formula Two engine available the F2 cars could neither be known as Renaults or Alpines while powered by Ford-Cosworth and BMW engines and were labelled Elf 2 and later Elf 2J. A Renault 2.0 litre engine arrived in time for Jean-Pierre Jabouilleto win the European Formula 2 Championship in 1976. By this time Alpine with Jabouille driving had built a Formula One car as a testing mule which lead directly to their entry into the Formula One world championship in 1977. A second European Formula 2 championship followed with René Arnoux in 1977 with the customer Martini team, before Alpine sold the F2 operation to Willi Kauhsen to concentrate on the Le Mans and Formula One programs.

Alpine Renault continued to develop their range of models all through the 1980s. The A310 was the next modern interpretation of the A110. The Alpine A310 was a sports car with a rear-mounted engine and was initially powered by a four-cylinder 1.6 L sourced Renault 17 TS/Gordini engine. In 1976 the A310 was restyled by Robert Opron and fitted with the more powerful and newly developed V6 PRV engine. The 2.6 L motor was modified by Alpine with a four-speed manual gearbox. Later they would use a Five-speed manual gearbox and with the group 4 model get a higher tune with more cubic capacity and 3 twin barrel Weber carburetors.

After the A310 Alpine transformed into the new Alpine GTA range produced from plastic and polyester components, commencing with normally aspirated PRV V6 engines. In 1985 the V6 Turbo was introduced to complete the range. This car was faster and more powerful than the normally aspirated version. In 1986 polyester parts were cut for the first time by robot using a high pressure (3500 bar) water jet, 0.15 mm (0.01 in) in diameter at three times the speed of sound. In the same year the American specification V6 Turbo was developed.

In 1987 fitment of anti-pollution systems allowed the V6 Turbo to be distributed to Switzerland, Germany, Austria and the Netherlands. 1989 saw the launch of the limited edition GTA Mille Miles to celebrate Alpine’s 35th anniversary. Production was limited to 100 cars, all fitted with ABS braking, polished wheels, special leather interior and paintwork. This version was not available in RHD.

1990 saw the launch of the special edition wide-bodied GTA Le Mans. Otherwise identical mechanically to the V6 Turbo, the engine was fitted with a catalytic converter and power was reduced to 185 bhp (138 kW). This model was available in the UK and RHD versions carried a numbered plaque on the dashboard. The Le Mans is the most collectable and valuable GTA derivative, since only 325 were made (299 LHD and 26 RHD). These were available from Renault dealers in the UK and the country’s motoring press are belatedly recognising the GTA series as the ‘great unsung supercar of the 1980s’

The Alpine A610 was launched in 1991. It was re-styled inside and out but was still recognisable as a GTA derivative. The chassis structure was extensively reworked but the central box principal remained the same. The front was completely re-designed the interior was also greatly improved. Air-conditioning and power steering were fitted as standard. The total production run for A610s derivatives was 818 vehicles 67 RHD and 751 LHD. After production of the A610 ended, the Alpine factory in Dieppe produced the Renault Sport Spider and a new era was to begin.

The last Alpine, an A610, rolled off the Dieppe line on 7 April 1995, Renault abandoning the Alpine name. This was always a problem in the UK market. Alpines could not be sold in the UK under their own name because Sunbeam owned the trade mark (because of the mid-50s Sunbeam Alpine Mk I). In the 1970s, for example Dieppe were building modified Renault 5s for the world wide market. The rest of the world knew them as R5 Alpines but in the UK they had to be renamed to R5 Gordini. Strangely enough with the numerous company takeovers that have occurred, it is another French company, PSA Peugeot Citroën, who now own the BritishAlpine trademark.

The Alpine factory in Dieppe continues to expand; in the 1980s they built the special R5 Turbo cars, following the rear engined formula they have always used. They built all Clio Williams and RenaultSport Spiders. The factory proudly put its Alpine badges on the built early batches of the mid engined Clio series one Clio V6. The Clio Series 2 was also assembled there with more recent RenaultSport Clio 172 and RenaultSport Clio 182s.

Between 1989 and 1995, a new Alpine named the A710 “Berlinette 2”, was designed and 2 prototypes were built. Due to the cost of the project (600 millions Francs), and as adding modern equipment and interior would compromise the price and performances, the project was canceled.

The Dieppe factory is known as the producer of Renault Sport models that are sold worldwide. This was originally the “Alpine” factory that Renault gained when they acquired the brand in 1973. Some of the Renault Sport models produced in Dieppe are currently the Mégane Renault Sport, Clio Renault Sport and the new Mégane Renault Sport dCi is to be built on Renault’s Dieppe assembly line. All the RenaultSport track-, tarmac- and gravel-racing Meganes and Clios are also made in the Dieppe factory.

In October 2007, it was reported that Renault’s marketing boss Patrick Blain has revealed that there were plans for several sports cars in Renault’s future lineup, but stressed that the first model wouldn’t arrive until after 2010. Blain confirmed that Renault is unlikely to pick a new name for its future sports car and will probably go with Alpine to brand it. Blain described it as being a “radical sports car” and not just a sports version of a regular model.

The new Alpine sports car will likely have a version of the Nissan GT-R‘s Premium Midship platform.

In France there is a large network of Alpine enthusiasts clubs. Clubs exist in many countries including the UK, USA, Australia, Japan.

In February 2009, Renault confirmed that plans to revive the Alpine brand have been frozen as a direct result of the 2008-2009 global financial crisis and recession.

In May 2012, images of a new Renault Alpine concept titled as Renault Alpine A110-50 were leaked prior to its debut in Monaco. Its styling was based on the Renault DeZir presented in 2010.

In November 2012, Renault and Caterham Cars announced the purchasing by the latter of an 50% stake in the Renault’s wholly owned subsidiary Société des Automobiles Alpine to create a joint venture (Société des Automobiles Alpine Caterham or SAAC) owned equally by both parts, with the aim of developing affordable sport cars under the Alpine (for Renault) and Caterham (for Caterham Cars) brands, which would be available in 2016. In this partnership, Caterham acquired 50% ownership of the Renault’s Dieppe assembly plant assets. On 10 June 2014, Renault announced it would be repurchasing the stake from Caterham Cars in SAAC, renaming it Société des Automobiles Alpine.

In 2013, as part of the promotional activities for the future launching of Alpine roadcars, Renault partnered with Signatech to enter a Nissan-powered, Oreca-built prototype into the European Le Mans Series championship’s LMP2 class. Signatech-Alpine achieved the teams’ championship. They returned for the 2014 season.

Alpine A360, Formula Three

Alpine A367, Formula Two, also known as Elf 2

Alpine A440

Alpine A450 (revised Oreca 03)

Currently, the old Alpine factory is the manufacturing site for Renault Sport Technologies-developed cars.

The models in production include:

Renault Alpines were never imported into Australia, but as enthusiasts wanted more than just the normal local Renault offerings, Renault Alpine enthusiasts have privately imported the following models into Australia. Currently there are A110, A310, GTA-atmo-turbo-lemans, A610, Renault 5 Turbo and Renault Sport Spiders registered.

An example of an Alpine weekend was held in Victoria with attendees from South Australia, Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland. There were 17 Alpines and 2 Renault 5 Turbos. The Alpine model breakdown was: A110: 5 | A310 (4 cyl): 3 | A310 (6 cyl): 4 | GTA Turbo: 2| GTA atmo: 3

The Renault Alpine 108 was produced in Brazil from 1962 to 1966, under license by Willys-Overland do Brasil, branded “Willys Interlagos”. It was the first Brazilian sports car.

Bulgaria produced its own version of the Renault Alpine, known as Bulgaralpine from 1967 to 1969. About 100 vehicles were produced.

A few examples of the Alpine GTA were imported into the Canadian province of Quebec with the expectation that AMC/Renault would be adding the model to their Canadian lineup. The GTA was designed by Renault to meet North American standards however plans to inport the GTA to North America were cancelled by Chrysler shortly after their takover of AMC.

That’s all about Alpine Automobiles and his predisessor Sunbeam what I could find.

E28 5 series compact mid-sized sedan 1981–1988

E28 5 series compact mid-sized sedan 1981–1988

E30 3 series sedan, convertible and estate 1982–1994

E30 3 series sedan, convertible and estate 1982–1994

Z1 roadster 1989–1991

Z1 roadster 1989–1991

E32 7 series large sedan 1986–1994

E32 7 series large sedan 1986–1994

E34 5 series mid-sized sedan 1988–1996

E34 5 series mid-sized sedan 1988–1996

E31 8 series 2+2 coupe 1989–1999

E31 8 series 2+2 coupe 1989–1999

1990s

E36 3 series sedan, coupe, convertible and touring 1990–2000

E36 3 series sedan, coupe, convertible and touring 1990–2000

E36 Compact hatchback 1993–2000 (first-generation Compact)

E36 Compact hatchback 1993–2000 (first-generation Compact)

Z3 coupe and roadster 1996–2002

Z3 coupe and roadster 1996–2002

M coupe 1998–2002 (first-generation M Coupe)

E38 7 series large sedan 1994–2001

E38 7 series large sedan 1994–2001

E39 5 series mid-sized sedan 1995–2003

E39 5 series mid-sized sedan 1995–2003

E53 X5 mid-sized SUV 1999–2006 (BMW’s first SUV)

E53 X5 mid-sized SUV 1999–2006 (BMW’s first SUV)

E46 3 series sedan, coupe, convertible and touring 1998–2006

E46 3 series sedan, coupe, convertible and touring 1998–2006

E52 Z8 roadster 1999–2003

E52 Z8 roadster 1999–2003

2000s

E46 Compact hatchback 2000–2004 (second-generation Compact)

E46 Compact hatchback 2000–2004 (second-generation Compact)

E65/66/67/68 large sedan 2002–2008

E65/66/67/68 large sedan 2002–2008

E85/E86 Z4 roadster/coupe 2002–2008 (first-generation Z4)

E85/E86 Z4 roadster/coupe 2002–2008 (first-generation Z4)

E83 X3 crossover SUV 2003–2010

E83 X3 crossover SUV 2003–2010

E60 5 series mid-sized sedan 2003–2010

E60 5 series mid-sized sedan 2003–2010

E63/E64 mid-sized coupe/convertible 2003–2011

E63/E64 mid-sized coupe/convertible 2003–2011

E61 estate 2004–2011

E70 X5 mid-sized SUV 2006–present (second-generation X5)

E70 X5 mid-sized SUV 2006–present (second-generation X5)

E71 X6 mid-sized crossover 2008–present (2-door version of X5)

E71 X6 mid-sized crossover 2008–present (2-door version of X5)

E81/E87 1 series hatchback 2004–2011 (first-generation 1 Series)

E81/E87 1 series hatchback 2004–2011 (first-generation 1 Series)

E82/E88 1 series small coupe/convertible 2007–2011

X1 compact crossover SUV 2009–present

X1 compact crossover SUV 2009–present

X3 crossover 2004–present

X3 crossover 2004–present

E90/E91/E92/E93 3 series sedan/touring/coupe/convertible 2005–2011

E90/E91/E92/E93 3 series sedan/touring/coupe/convertible 2005–2011

F01/F02/F03/F04 7 series large sedan 2008-

F01/F02/F03/F04 7 series large sedan 2008-

E89 roadster 2009–present (second-generation Z4)

E89 roadster 2009–present (second-generation Z4)

F10 5 series mid-sized sedan 2009–present

F10 5 series mid-sized sedan 2009–present

F11 5 series mid-sized estate 2009–present

F07 5 series GT 4-door coupe 2009–present

F07 5 series GT 4-door coupe 2009–present

F12/F13 6 series midsized coupe/convertible 2011–present

F12/F13 6 series midsized coupe/convertible 2011–present

F20/F21 1 series hatchback 2011–present

F25 X3 crossover SUV 2011–present

F30 3 series compact sedan 2012–present

F15 X5 mid-sized SUV 2013–present

F15 X5 mid-sized SUV 2013–present

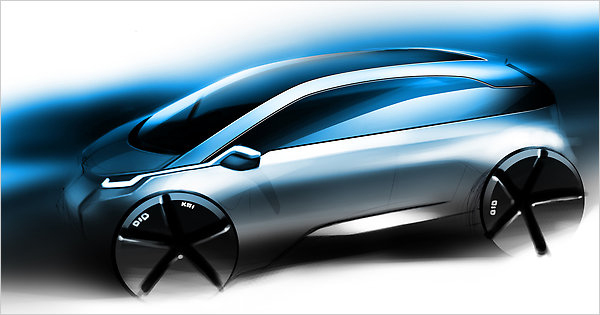

i3 compact electric city car 2013–present

i3 compact electric city car 2013–present

BMW X4 2014–present

1972 Turbo

1972 Turbo

1990 M8: A high-performance version of the 8 Series coupe designed to compete with the likes of Ferrari.

1991 E1 Electric car.

1993 Z13

1995 Just 4/2 A two-seater open sports car with a BMW K series motorbike engine positioned behind the driver and passenger.

1995 Just 4/2 A two-seater open sports car with a BMW K series motorbike engine positioned behind the driver and passenger.

1995 Z18

1995 Z18

1997 Z07 Concept Previewed the Z8 sports car

1999 Z9 Concept Designed by Adrian van Hooydonk that marked a departure from BMW’s traditional conservative style, causing some controversy among BMW enthusiasts. This later on became the 6 Series.

1999 Z9 Concept Designed by Adrian van Hooydonk that marked a departure from BMW’s traditional conservative style, causing some controversy among BMW enthusiasts. This later on became the 6 Series.

750hL At Expo 2000. A 7 Series sedan powered by a hydrogen fuel cell engine. As of March 2007, there are as many as 100 750hL vehicles worldwide for testing and publicity purposes.

2001 X-Coupe

2001 X-Coupe

2002 xActivity Concept Previewed the E83 X3

2002 CS1 Concept Previewed the E8x generation 1 series

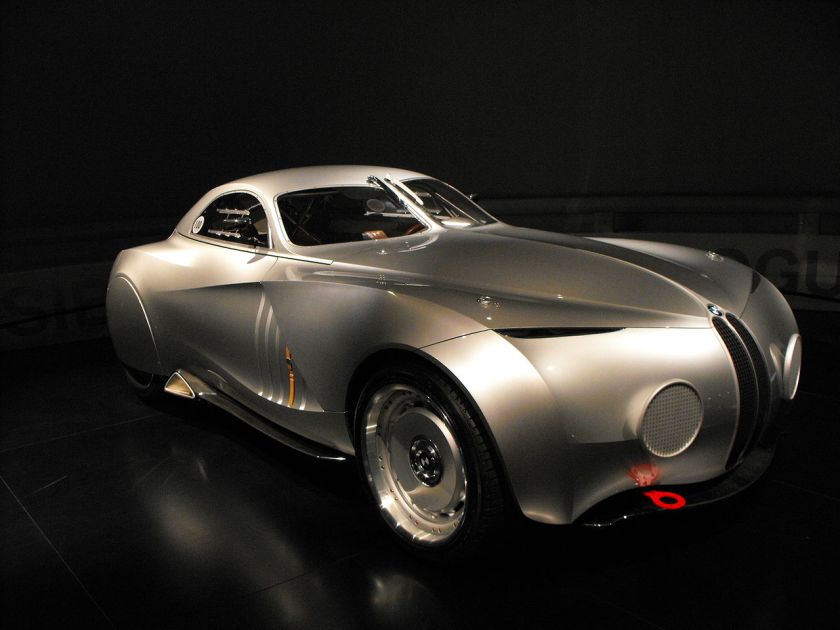

2006 BMW Mille Miglia Coupe Concept

2007 Concept CS

2008 Concept 1 Series tii Previewed BMW Performance Parts to be made available on the E82 1 Series

2008 GINA Based on the structure of a Z8 with a light fabric skin and hydro-electric technology to allow the shape to change.

2008 GINA Based on the structure of a Z8 with a light fabric skin and hydro-electric technology to allow the shape to change.

2008 Concept X1 Previewed a compact Sports Activity Vehicle

2008 Concept 5 Series Gran Turismo First of the BMW Progressive Activity Series

2008 Concept 5 Series Gran Turismo First of the BMW Progressive Activity Series

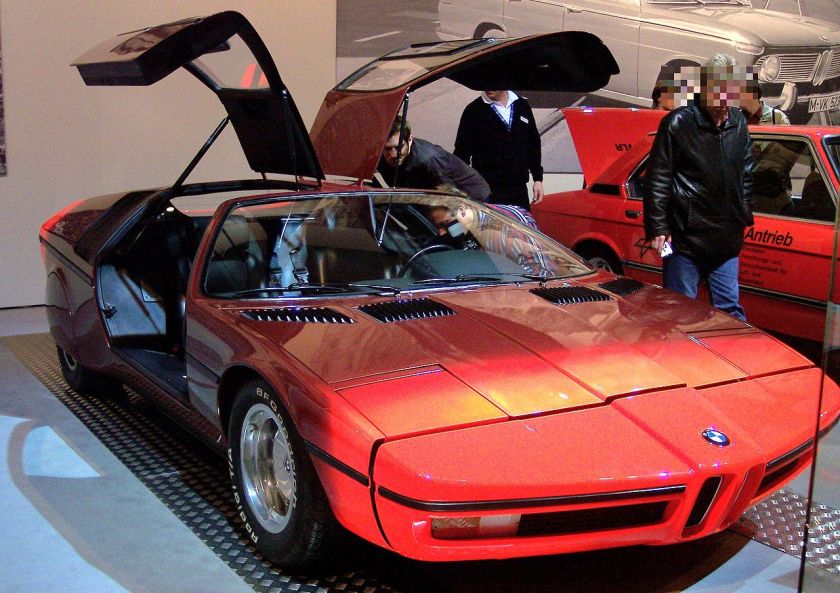

2008 M1 Hommage

2009 C1-E An electric version of the C1 scooter

2009 C1-E An electric version of the C1 scooter

2009 Vision EfficientDynamics BMWi8 concept

2009 Vision EfficientDynamics BMWi8 concept

2010 5 Series Concept ActiveHybrid

2010 Concept Gran Coupe Previewed the F14 6 series Gran Coupe

2010 Concept 6 Series Coupe Previewed the F12 / F13 6 Series Coupe and Convertible

2010 Vision ConnectedDrive Previewed future BMW communications technology

2010 Vision ConnectedDrive Previewed future BMW communications technology

2011 328 Hommage

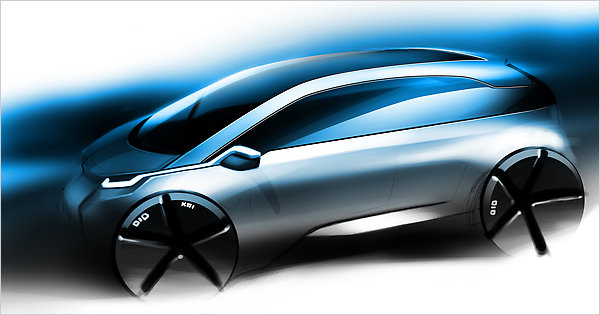

2011 i3 Concept Previewed the i3 premium compact electric vehicle

2011 i3 Concept Previewed the i3 premium compact electric vehicle

2011 i8 Concept Previewed the future production i8 plug-in hybrid electric sports car

2012 M135i Concept Previewed the M Performance variant of the F20 1-Series hatchback

2012 Zagato Coupe

2012 Zagato Roadster

2012 Concept Active Tourer Previewed future FWD BMW vehicle architecture and the new 2-Series Gran Turismo

2012 i3 Concept Coupe Previewed a potential coupe version of the future production i3 premium compact electric vehicle

2012 i8 Concept Spyder Previewed a potential spyder version of the future production i8 plug-in hybrid electric sports car

2013 BMW Concept X4 Previewed the F26 X4 Sports Activity Coupe

2013 Concept 4 Series Coupe Previewed the F32 4-Series Coupe

2013 BMW Pininfarina Gran Lusso Coupe

2013 BMW Concept M4 Previewed the F82 M4 and F80 M3

2013 BMW Concept X5 eDrive Previewed the future F15 X5 plug-in hybrid

2014 Vision Future Luxury Concept Previewed the G11 7-Series and potential 9-Series flagship

BMW 501 — (1952–1958) 6 cylinder Limousine

BMW 501 — (1952–1958) 6 cylinder Limousine

BMW 502 — (1954–1964) 8 cylinder Limousine

BMW 502 — (1954–1964) 8 cylinder Limousine

BMW 503 — (1956–1959) 8 cylinder Coupe and Cabriolet

BMW 503 — (1956–1959) 8 cylinder Coupe and Cabriolet

BMW 507 — (1955–1959) 8 cylinder Roadster

BMW 507 — (1955–1959) 8 cylinder Roadster

BMW 3200 CS — (1956–1959) 8 cylinder Coupe and 1 Cabriolet

BMW 3200 CS — (1956–1959) 8 cylinder Coupe and 1 Cabriolet

BMW Typ100 — (1955–1962) Isetta

BMW Typ100 — (1955–1962) Isetta

BMW Typ106 — (1957–1959) 600

BMW Typ106 — (1957–1959) 600

bmw-700

BMW Typ110 – (1961–1964) 700 Cabriolet

BMW Typ110 – (1961–1964) 700 Cabriolet

BMW Typ114 — (1966–1976) 1600-2, 1602-2002TI, 1502

BMW Typ115 — (1963–1964) 1500

BMW Typ115 — (1963–1964) 1500

BMW Typ118 — (1963–1971) 1800-1800TI/SA

BMW Typ118 — (1963–1971) 1800-1800TI/SA

BMW Typ120 — (1966–1970) New Class Coupe 2000C/CS

BMW Typ121 — (1966–1972) 2000-2000tii

BMW Typ121 — (1966–1972) 2000-2000tii

BMW E3 — (1968–1977) 2.5, 2.8, 3.0, 3.3 “New Six” Sedans

BMW E3 — (1968–1977) 2.5, 2.8, 3.0, 3.3 “New Six” Sedans

BMW E9 — (1969–1975) 2800CS, 3.0CS, 3.0CSL “New Six” Coupes

BMW E9 — (1969–1975) 2800CS, 3.0CS, 3.0CSL “New Six” Coupes

BMW M535i M5— (1974–1981) 5 Series Sedan/M535i Sedan

BMW M535i M5— (1974–1981) 5 Series Sedan/M535i Sedan

BMW E21 — (1976–1983) 3 Series Sedan/Convertible

BMW E21 — (1976–1983) 3 Series Sedan/Convertible

BMW E23 — (1977–1986) 7 Series Sedan

BMW E23 — (1977–1986) 7 Series Sedan

BMW M635i — (1976–1989) 6 Series Coupe/M635i Coupe

BMW M635i — (1976–1989) 6 Series Coupe/M635i Coupe

BMW E26 — (1978–1981) M1 Coupe

BMW E26 — (1978–1981) M1 Coupe

BMW M5 E28 — (1981–1987) 5 Series Sedan/M5 Sedan

BMW M3 E30 — (1983–1991) 3 Series Sedan/Coupe/Touring/Convertible/M3 Coupe/Convertible

BMW M3 E30 — (1983–1991) 3 Series Sedan/Coupe/Touring/Convertible/M3 Coupe/Convertible

BMW Z1 — (1988–1991) Z1 Roadster

BMW E31 — (1989–1999) 8 Series Coupe

BMW E32 — (1986–1994) 7 Series Sedan

BMW E32 — (1987–1994) 7 Series Sedan long wheelbase

BMW M5 E34 — (1988–1995) 5 Series Sedan/M5 Sedan

BMW E34 — (1991–1996) 5 Series Touring

BMW M3 E36 — (1991–1999) 3 Series Coupe/M3 Coupe

BMW E36 — (1994–1999) 3 Series Touring

BMW M3 E36 — (1991–1999) 3 Series Sedan/M3 Sedan

BMW M3 E36 — (1993–1999) 3 Series Convertible/M3 Convertible

E36/5 — (1994–2000) 3 Series Compact

BMW M Roadster E36/7 — (1995–2002) Z3 Roadster/Z3 M Roadster

BMW M Coupe E36/8 — (1997–2002) Z3 Coupe/Z3 M Coupe

BMW E38 — (1994–2001) 7 Series Sedan

BMW E38 — (1994–2001) 7 Series Sedan

BMW E38/2 — (1994–2001) 7 Series Sedan long wheelbase

BMW E38/3 — (1998–2001) 7 Series Sedan Protection

BMW M5 E39 — (1995–2003) 5 Series Sedan/M5 Sedan

BMW E39/2 — (1996–2003) 5 Series Touring

BMW M3 E46 — (1999–2006) 3 Series Coupe/M3 Coupe

BMW E46 — (1999–2006) 3 Series Touring

BMW E46 — (1998–2006) 3 Series Sedan

BMW E46/5 — (2000–2004) 3 Series Compact

BMW M3 E46 — (1999–2006) 3 Series Convertible/M3 Convertible

BMW E52 — (1999–2003) Z8 Roadster

BMW E52 — (1999–2003) Z8 Roadster

BMW E53 — (1999–2006) X5 Sport Activity Vehicle

BMW E53 — (1999–2006) X5 Sport Activity Vehicle

BMW M5 E60 — (2003–2010) 5 Series Sedan/M5 Sedan

BMW M5 E61 — (2003–2007) 5 Series Touring/M5 Touring

BMW M6 E63 — (2003–2010) 6 Series Coupe/M6 Coupe

BMW M6 E64 — (2003–2010) 6 Series Convertible/M6 Convertible

BMW E65 — (2001–2007) 7 Series short wheelbase

BMW E65 — (2001–2007) 7 Series short wheelbase

BMW E66 — (2001–2007) 7 Series long wheelbase

BMW E67 — (2001–2007) 7 Series Protection

BMW E68 — (2005–2007) Hydrogen 7

BMW X5 M — (2007–2013) X5 Sports Activity Vehicle/X5 M Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW X6 M — (2008–present) X6 Sports Activity Coupe/X6 M Sports Activity Coupe

BMW E72 — (2009–2011) X6 Hybrid Sports Activity Coupe

BMW E81 — (2007–2012) 1 Series Hatchback 3-door

BMW E81 — (2007–2012) 1 Series Hatchback 3-door

BMW 1M Coupe — (2007–2013) 1 Series Coupe/1M Coupe

BMW E83 — (2004–2012) X3 Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW E84 — (2009–present) X1 Compact Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW M Roadster E85 — (2002–2008) Z4 Roadster/Z4 M Roadster

BMW M Coupe E86 — (2006–2008) Z4 Coupe/Z4 M Coupe

BMW E87 — (2004–2011) 1 Series Hatchback 5-door

BMW E88 — (2008–2013) 1 Series Convertible

BMW E89 — (2009–present) Z4 Roadster

BMW M3 E90 — (2005–2011) 3 Series Sedan/M3 Sedan

BMW E91 — (2005–2011) 3 Series Touring

BMW M3 E92 — (2006–2013) 3 Series Coupe/M3 Coupe

BMW M3 E93 — (2007–2013) 3 Series Convertible/M3 Convertible

BMW F01 — (2008–present) 7 Series

BMW F01 — (2008–present) 7 Series

BMW F02 — (2009–present) 7 Series long wheelbase

BMW F03 — (2008–present) 7 Series Protection

BMW F04 — (2011–present) 7 Series ActiveHybrid

BMW M6 F06 — (2011–present) 6 Series Gran Coupe/M6 Gran Coupe

BMW F07 — (2009–present) 5 Series Gran Turismo

BMW M5 F10 — (2011–present) 5 Series Sedan/M5 Sedan

BMW F11 — (2012–present) 5 Series Touring

BMW M6 F12 — (2011–present) 6 Series Coupe/M6 Coupe

BMW M6 F13 — (2011–present) 6 Series Convertible/M6 Convertible

BMW F15 — (2013–present) X5 Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW F16 — (2014) X6 Sports Activity Coupe

BMW F18 — (2010–present) 5 Series long wheelbase

BMW F20 — (2011–present) 1 Series Hatchback 5-door

BMW F21 — (2012–present) 1 Series Hatchback 3-door

BMW F22 — (2013–present) 2 Series Coupe

BMW F23 — (2014) 2 Series Convertible

BMW F25 — (2010–present) X3 Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW F26 — (2014–present) X4 Sports Activity Coupe

BMW F30 — (2012–present) — 3 Series Sedan

BMW F31 — (2012–present) 3 Series Touring

BMW F32 — (2013–present) 4 Series Coupe

BMW F33 — (2013–present) 4 Series Convertible

BMW F34 — (2013–present) 3 Series Gran Turismo

BMW F35 — (2012–present) 3 Series long wheelbase

BMW F36 — (2014) 4 Series Gran Coupe

BMW F45 — (2014) 2 Series Active Tourer

BMW F46 — (2014) 2 Series 7 Seat Gran Tourer

BMW F47 — (2017) X2 Compact Sports Activity Coupe

BMW F48 — (2015) X1 Compact Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW F49 — (2015) X1 7 Seat Compact Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW F52 — (2015–present) 1 Series Sedan

BMW F80 — (2014–present) M3 Sedan

BMW F82 — (2014–present) M4 Coupe

BMW F83 — (2014–present) M4 Convertible

BMW F85 — (2015) X5 M Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW F86 — (2015) X6 M Sports Activity Coupe

BMW F87 — (2015) M2 Coupe

BMW G01 — (2017) X3 Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW G11 740 — (2016) 7 Series short wheelbase

BMW G12 — (2016) 7 Series long wheelbase

BMW G30 — (2016) 5 Series

Since 1972, BMW model names have generally been a 3 digit number followed by 1, 2 or 3 letters

Commonly used letters at the end of the model name are:

For example, the BMW 760iL is a fuel-injected 7 Series with a long wheelbase and 6.0 liters of displacement. A 318i represents a 3 series with a 1.8 L engine, in this case the “i” means that the engine is fuel-injected. This badge was used for successive generations, E65 and F01.

When ‘L’ supersedes the series number (e.g. L6, L7, etc.) it identifies the vehicle as a special luxury variant, featuring extended leather and special interior appointments. The L7 is based on the E23 and E38, and the L6 is based on the E24.

When ‘X’ is capitalized and supersedes the series number (e.g. X3, X5, etc.) it identifies the vehicle as one of BMW’s Sports Activity Vehicles (SAV), their brand of crossovers. Predominantly these vehicles feature BMW’s xDrive, though both the E84 X1 and the F15 X5 offer rear wheel drive, badged as sDrive vehicles. The second number in the ‘X’ series denotes the platform that it is based upon, for instance the X5 is derived from the 5 Series. Unlike BMW cars, the SAV’s main badge does not denote engine size, the engine is instead indicated on side badges.

The ‘Z’ identifies the vehicle as a two-seat roadster (e.g. Z1, Z3, Z4, etc.). ‘M’ variants of ‘Z’ models have the ‘M’ as a suffix or prefix, depending on country of sale (e.g. ‘Z4 M’ is ‘M Roadster’ in Canada).

Previous X & Z vehicles had ‘i’ or ‘si’ following the engine displacement number (denoted in liters). BMW is now globally standardizing this nomenclature on X & Z vehicles by using ‘sDrive’ or ‘xDrive’ (simply meaning rear or all wheel drive, respectively) followed by two numbers which vaguely represent the vehicle’s engine (e.g. Z4 sDrive35i is a rear wheel drive Z4 roadster with a 3.0 L twin-turbo fuel-injected engine).

The ‘s’ code has meant different things at different times. The E30 325iS was an options pack for the 325i, however the E30/E36 318iS models used different engines to E30/E36 318i models. The ‘s’ code was dropped in 1999 after the 325tds model (the last use in North America was for the 1995 325is). However, the ‘s’ code was revived on the 2011 model year BMW 335is and BMW Z4 sDrive35is. The 335is has a more powerful engine, sports options and an optional dual clutch transmission that slots between the regular 335i and top-of-the-line M3.

The ‘M’ – for Motorsport – identifies the vehicle as a high-performance model of a particular series (e.g. M3, M5, M6, etc.). For example, the M6 is the highest performing vehicle in the 6 Series lineup. Although ‘M’ cars should be separated into their respective series platforms, it is very common to see ‘M’ cars grouped together as its own lineup on the official BMW website.

A similar nomenclature is used by BMW Motorrad for their motorcycles.

There are exceptions to the numbering nomenclature, most commonly relating to SUV models, turbocharged engines and differing specification despite the same engine capacity.

SUV models

The M versions of the X5 M and X6 M, could not follow the regular naming convention, since “MX5” was used for Mazda‘s MX-5 Miata and MX-6.

Turbocharged engines

The 2008 BMW 335i and 535i also have 3.0-liter engine; however the engines are twin-turbocharged (N54) which is not identified by the nomenclature. Nonetheless the ’35’ indicates a more powerful engine than previous ’30’ models that have the naturally aspirated N52 engine. The 2011 BMW 740i and 335is share the same twin-turbo 3.0 N54 engine, although the badging is not consistent (’40’ and ‘s’). Due to the move to turbocharged engines, the 2009 750i has a 4.4 L turbocharged engine, compared with a 4.8 L naturally-aspirated engine for the 2006 750i.

Due to the increased use of turbocharging recently, it will become increasingly common for the last two digits to not represent the engine capacity (for example the F30 328i uses a turbocharged 2.0-litre engine).

Different specification levels but same engine capacity

In the 2008 model year, the BMW 125i, 128i, 328i, and 528i all had 3.0 naturally aspirated engines (N52), not a 2,500 cc or 2,800 cc engine as the series designation number would lead one to believe. The ’28’ is to denote a detuned engine in the 2008 cars, compared to the 2006 model year ’30’ vehicles (330i and 530i) whose 3.0 L naturally aspirated engines are from the same N52 family but had more output.

A similar situation occurred with the E36/E46 323i and E39 523i models. These models all used 2.5-litre engines. However, the previous 325i and 525i models were higher in the model range than their replacements, therefore the replacements were called 323i and 523i (which also provided a bigger gap to the future 328i and 528i models). BMW has not produced a 2.3-litre gasoline engine since the early 1990s.

The opposite situation occurred with the 1996 E36 318i, since it used a 1.9 L engine (M44) as opposed to the 1.8 L (M42) used in the 1992 to 1995 models. This was done to avoid changing the model code for the base model (i.e. otherwise consumers would need to be taught that the base model was now called 319i).

Another example of an exception is the 1980s 325e and 525e models. These cars actually used 2.7-litre engines (which were tuned for fuel economy rather than power).

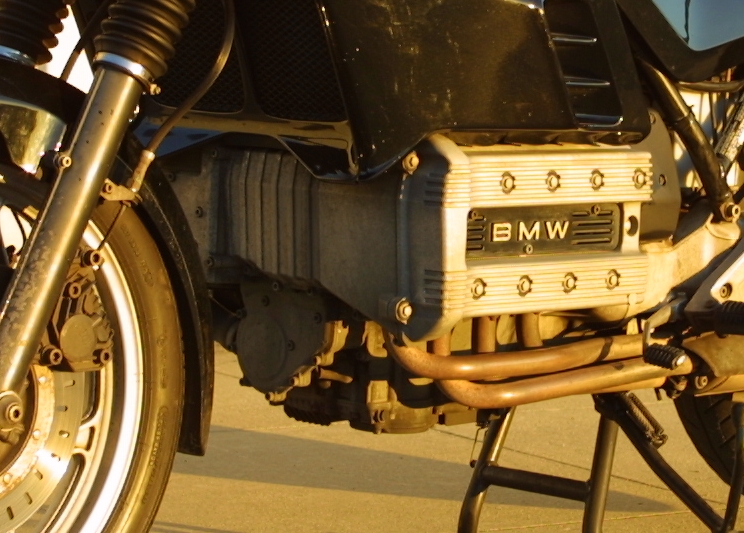

BMW Motorrad has produced motorcycles bearing the BMW name since the introduction of the BMW R32 in 1923. Prior to that date it produced engines for other manufacturers’ motorcycles.

The New Class (German: Neue Klasse) was a line of compact sedans and coupes starting with the 1962 1500 and continuing through the last 2002s in 1977. Powered by BMW’s celebrated four-cylinder M10 engine, the New Class models had a fully independent suspension, MacPherson struts in front, and front disc brakes. Initially a family of four-door sedans and two-door coupes, the New Class line was broadened to two-door sports sedans with the addition of the 02 Series 1600 and 2002 in 1966.

Sharing little in common with the rest of the line beyond power train, the sporty siblings caught auto enthusiasts’ attention and established BMW as an international brand. Precursors to the famed BMW 3 Series, the two-doors’ success cemented the firm’s future as an upper tier performance car maker. New Class four-doors with numbers ending in “0” were replaced by the larger BMW 5 Series in 1972. The upscale 2000C and 2000CS coupes were replaced by the six-cylinder BMW E9, introduced in 1969 with the 2800CS. The 1600 two-door was discontinued in 1975, and the 2002 was replaced by the 320i in 1975.

The 1 Series, originally launched in 2004, is BMW’s smallest car. Currently available are the second generation hatchback (F20) and first generation coupe/convertible (E82/E88). The 3 Series, a compact executive carmanufactured since model year 1975, is currently in its sixth generation (F30); models include the sport sedan (F30), and fourth generation station wagon (F30), and convertible (E93), and the Gran Turismo. In 2014, the 4 Series has been released and replaced the 3 Series Coupe and Convertible. The 5 Series is a mid-size executive car, available in sedan (F10) and station wagon (F11) forms. The 5 Series Gran Turismo (F07), which debuted in 2010, created a segment between station wagons and crossover SUV.  BMW Z4 (E89)

BMW Z4 (E89)

BMW’s full-size flagship executive sedan is the 7 Series. Typically, BMW introduces many of their innovations first in the 7 Series, such as the iDrive system. The 7 Series Hydrogen, having one of the world’s first hydrogenfueled internal combustion engines, is fueled by liquid hydrogen and emits only clean water vapor. The latest generation (F01) debuted in 2009. Based on the 5 Series’ platform, the 6 Series is BMW’s grand touring luxury sport coupe/convertible (F12/F13). A 2-seater roadster and coupe which succeeded the Z3, the Z4 has been sold since 2002.

The X3 (F25), BMW’s second crossover SUV (called SAV or “Sports Activity Vehicle” by BMW) debuted in 2010 and replaced the X3 (E83), which was based on the E46 3 Series’ platform, and had been in production since 2003. Marketed in Europe as an off-roader, it benefits from BMW’s xDrive all-wheel drive system. The all-wheel drive X5 (E53) was BMW’s first crossover SUV (SAV), based on the 5 Series, and is a mid-size luxury SUV (SAV) sold by BMW since 2000. A 4-seat crossover SUV released by BMW in December 2007, the X6 is marketed as a “Sports Activity Coupe” (SAC) by BMW. The X1 extends the BMW Sports Activity Series model lineup.

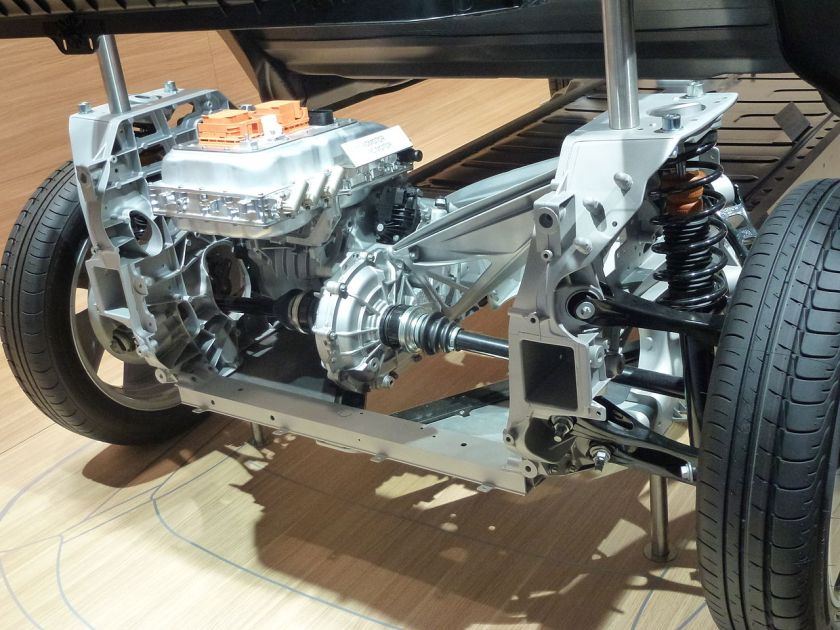

The BMW i is a sub-brand of BMW founded in 2011 to design and manufacture plug-in electric vehicles. The sub-brand initial plans called for the release of two vehicles; series production of the BMW i3 all-electric car began in September 2013, and the market launch took place in November 2013 with the first retail deliveries in Germany. The BMW i8 sports plug-in hybrid car was launched in Germany in June 2014. As of June 2015, over 30,000 i brand vehicles have been sold worldwide since 2013, consisting of over 26,000 i3s and about 4,500 i8s. The all-electric BMW i3 ranked among the world’s top ten best selling plug-in electric vehicles as of May 2015.

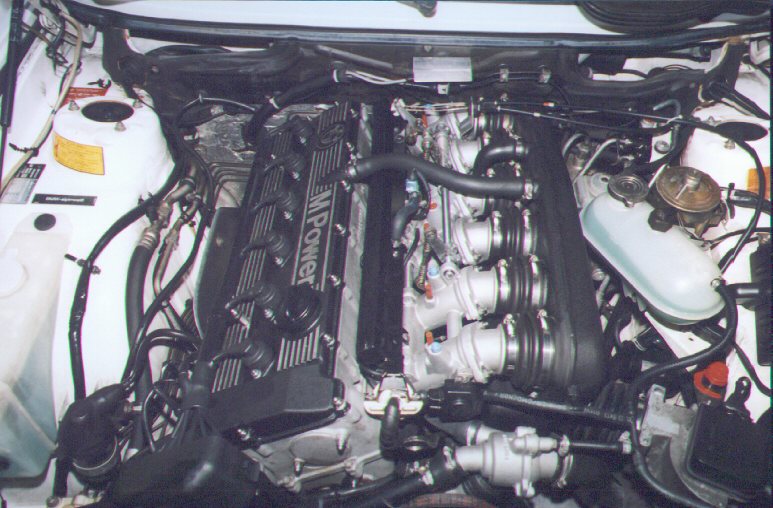

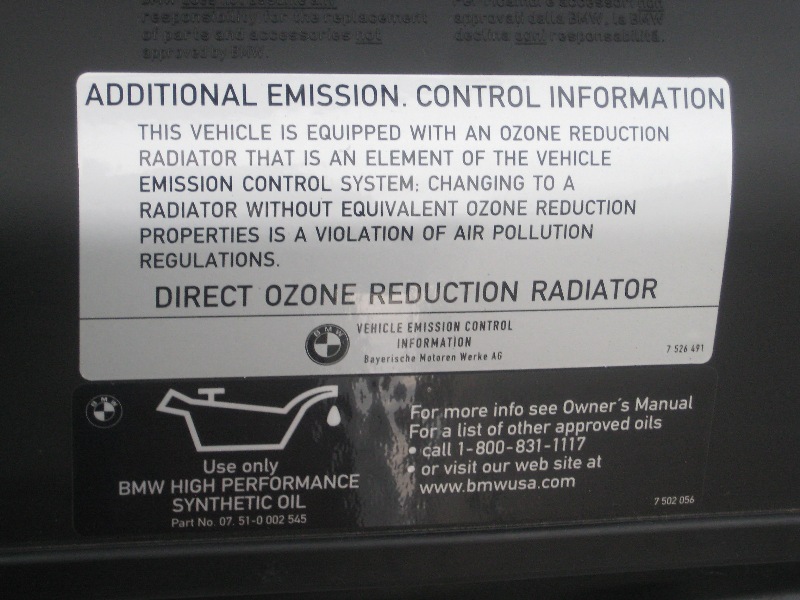

BMW produce a number of high-performance derivatives of their cars developed by their BMW M GmbH (previously BMW Motorsport GmbH) subsidiary.

The current M models are:

BMW has been engaged in motorsport activities since the dawn of the first BMW motorcycle in 1923.

BMW has a history of success in Formula One. BMW powered cars have won 20 races. In 2006 BMW took over the Sauber team and became Formula One constructors. In 2007 and 2008 the team enjoyed some success. The most recent win is a lone constructor team’s victory by BMW Sauber F1 Team, on 8 June 2008, at the Canadian Grand Prix with Robert Kubica driving. Achievements include:

BMW was an engine supplier to Williams, Benetton, Brabham, and Arrows. Notable drivers who have started their Formula One careers with BMW include Jenson Button, Juan Pablo Montoya, Robert Kubica and Sebastian Vettel.

In July 2009, BMW announced that it would withdraw from Formula One at the end of the 2009 season. The team was sold back to the previous owner, Peter Sauber, who kept the BMW part of the name for the 2010 season due to issues with the Concorde Agreement. The team has since dropped BMW from their name starting in 2011.

BMW has a long and successful history in touring car racing.