BMW chapter 2

1980s

E28 5 series compact mid-sized sedan 1981–1988

E28 5 series compact mid-sized sedan 1981–1988

E30 3 series sedan, convertible and estate 1982–1994

E30 3 series sedan, convertible and estate 1982–1994

Z1 roadster 1989–1991

Z1 roadster 1989–1991

E32 7 series large sedan 1986–1994

E32 7 series large sedan 1986–1994

E34 5 series mid-sized sedan 1988–1996

E34 5 series mid-sized sedan 1988–1996

E31 8 series 2+2 coupe 1989–1999

E31 8 series 2+2 coupe 1989–1999

1990s

E36 3 series sedan, coupe, convertible and touring 1990–2000

E36 3 series sedan, coupe, convertible and touring 1990–2000

E36 Compact hatchback 1993–2000 (first-generation Compact)

E36 Compact hatchback 1993–2000 (first-generation Compact)

Z3 coupe and roadster 1996–2002

Z3 coupe and roadster 1996–2002

M coupe 1998–2002 (first-generation M Coupe)

E38 7 series large sedan 1994–2001

E38 7 series large sedan 1994–2001

E39 5 series mid-sized sedan 1995–2003

E39 5 series mid-sized sedan 1995–2003

E53 X5 mid-sized SUV 1999–2006 (BMW’s first SUV)

E53 X5 mid-sized SUV 1999–2006 (BMW’s first SUV)

E46 3 series sedan, coupe, convertible and touring 1998–2006

E46 3 series sedan, coupe, convertible and touring 1998–2006

E52 Z8 roadster 1999–2003

E52 Z8 roadster 1999–2003

2000s

E46 Compact hatchback 2000–2004 (second-generation Compact)

E46 Compact hatchback 2000–2004 (second-generation Compact)

E65/66/67/68 large sedan 2002–2008

E65/66/67/68 large sedan 2002–2008

E85/E86 Z4 roadster/coupe 2002–2008 (first-generation Z4)

E85/E86 Z4 roadster/coupe 2002–2008 (first-generation Z4)

E83 X3 crossover SUV 2003–2010

E83 X3 crossover SUV 2003–2010

E60 5 series mid-sized sedan 2003–2010

E60 5 series mid-sized sedan 2003–2010

E63/E64 mid-sized coupe/convertible 2003–2011

E63/E64 mid-sized coupe/convertible 2003–2011

E61 estate 2004–2011

E70 X5 mid-sized SUV 2006–present (second-generation X5)

E70 X5 mid-sized SUV 2006–present (second-generation X5)

E71 X6 mid-sized crossover 2008–present (2-door version of X5)

E71 X6 mid-sized crossover 2008–present (2-door version of X5)

E81/E87 1 series hatchback 2004–2011 (first-generation 1 Series)

E81/E87 1 series hatchback 2004–2011 (first-generation 1 Series)

E82/E88 1 series small coupe/convertible 2007–2011

X1 compact crossover SUV 2009–present

X1 compact crossover SUV 2009–present

X3 crossover 2004–present

X3 crossover 2004–present

E90/E91/E92/E93 3 series sedan/touring/coupe/convertible 2005–2011

E90/E91/E92/E93 3 series sedan/touring/coupe/convertible 2005–2011

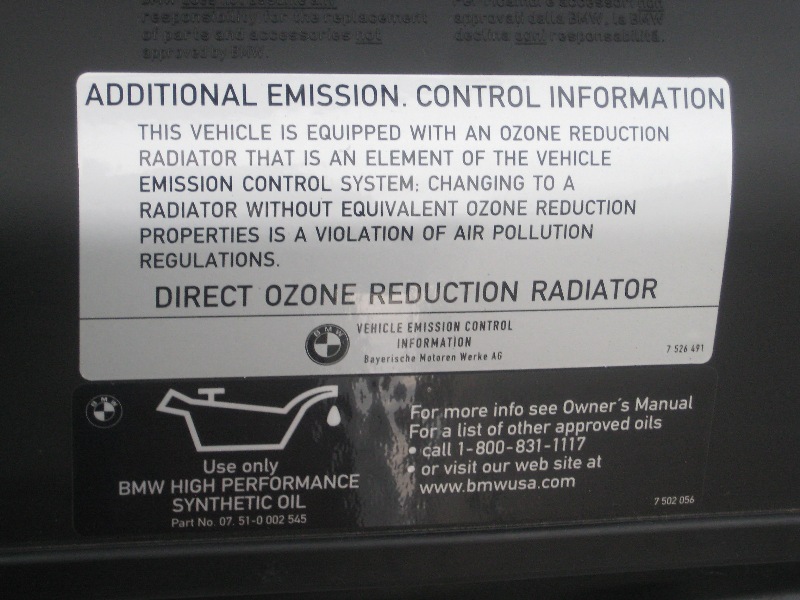

F01/F02/F03/F04 7 series large sedan 2008-

F01/F02/F03/F04 7 series large sedan 2008-

E89 roadster 2009–present (second-generation Z4)

E89 roadster 2009–present (second-generation Z4)

F10 5 series mid-sized sedan 2009–present

F10 5 series mid-sized sedan 2009–present

F11 5 series mid-sized estate 2009–present

F07 5 series GT 4-door coupe 2009–present

F07 5 series GT 4-door coupe 2009–present

2010s

F12/F13 6 series midsized coupe/convertible 2011–present

F12/F13 6 series midsized coupe/convertible 2011–present

F20/F21 1 series hatchback 2011–present

F25 X3 crossover SUV 2011–present

F30 3 series compact sedan 2012–present

F15 X5 mid-sized SUV 2013–present

F15 X5 mid-sized SUV 2013–present

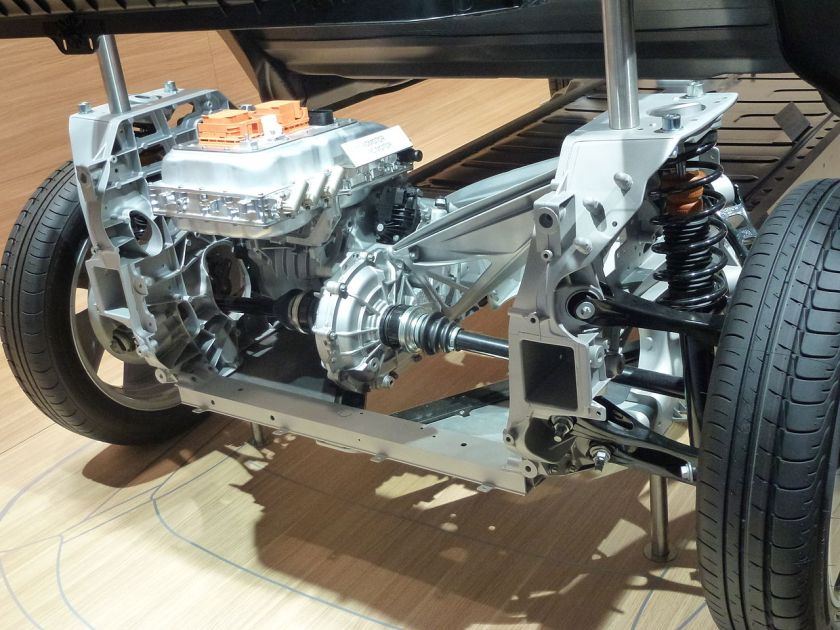

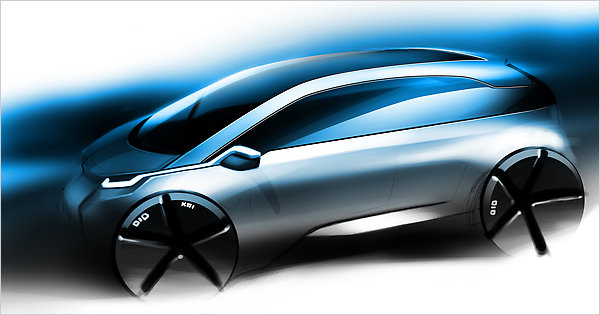

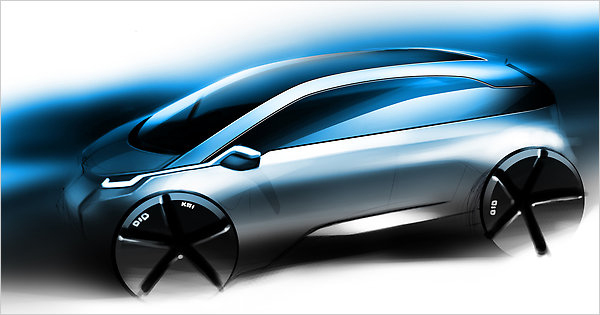

i3 compact electric city car 2013–present

i3 compact electric city car 2013–present

BMW X4 2014–present

Concepts and prototypes

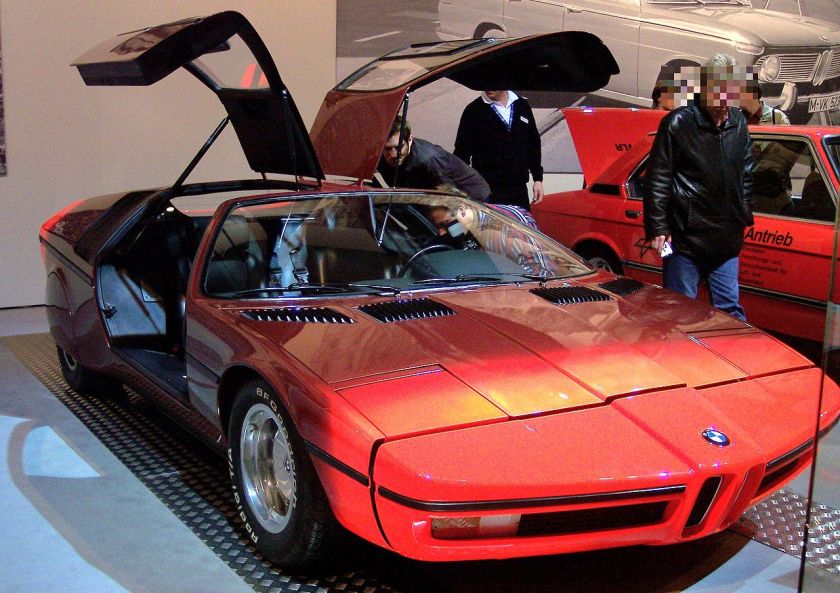

1972 Turbo

1972 Turbo

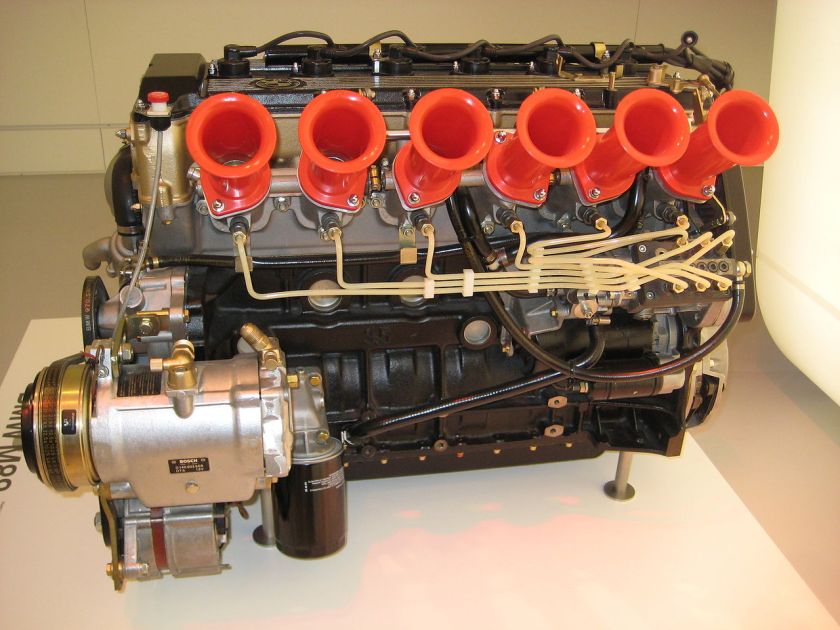

1990 M8: A high-performance version of the 8 Series coupe designed to compete with the likes of Ferrari.

1991 E1 Electric car.

1993 Z13

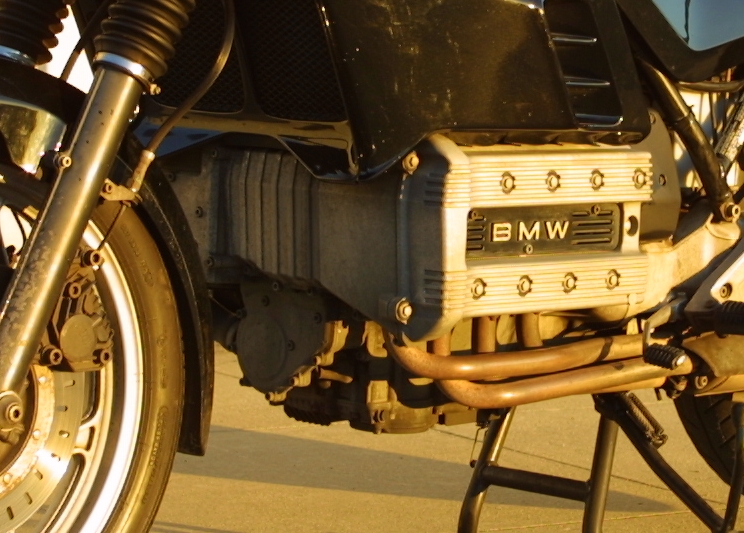

1995 Just 4/2 A two-seater open sports car with a BMW K series motorbike engine positioned behind the driver and passenger.

1995 Just 4/2 A two-seater open sports car with a BMW K series motorbike engine positioned behind the driver and passenger.

1995 Z18

1995 Z18

1997 Z07 Concept Previewed the Z8 sports car

1999 Z9 Concept Designed by Adrian van Hooydonk that marked a departure from BMW’s traditional conservative style, causing some controversy among BMW enthusiasts. This later on became the 6 Series.

1999 Z9 Concept Designed by Adrian van Hooydonk that marked a departure from BMW’s traditional conservative style, causing some controversy among BMW enthusiasts. This later on became the 6 Series.

750hL At Expo 2000. A 7 Series sedan powered by a hydrogen fuel cell engine. As of March 2007, there are as many as 100 750hL vehicles worldwide for testing and publicity purposes.

2001 X-Coupe

2001 X-Coupe

2002 xActivity Concept Previewed the E83 X3

2002 CS1 Concept Previewed the E8x generation 1 series

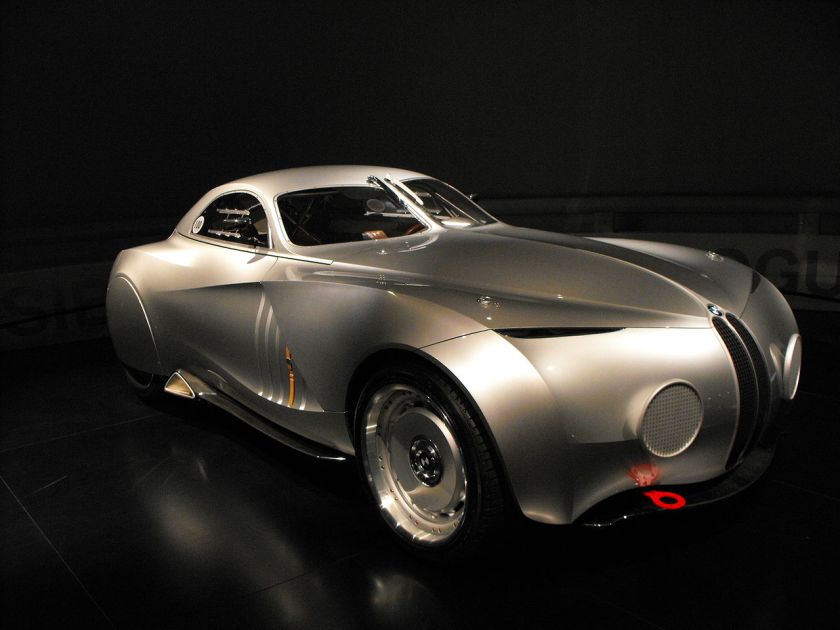

2006 BMW Mille Miglia Coupe Concept

2007 Concept CS

2008 Concept 1 Series tii Previewed BMW Performance Parts to be made available on the E82 1 Series

2008 GINA Based on the structure of a Z8 with a light fabric skin and hydro-electric technology to allow the shape to change.

2008 GINA Based on the structure of a Z8 with a light fabric skin and hydro-electric technology to allow the shape to change.

2008 Concept X1 Previewed a compact Sports Activity Vehicle

2008 Concept 5 Series Gran Turismo First of the BMW Progressive Activity Series

2008 Concept 5 Series Gran Turismo First of the BMW Progressive Activity Series

2008 M1 Hommage

2009 C1-E An electric version of the C1 scooter

2009 C1-E An electric version of the C1 scooter

2009 Vision EfficientDynamics BMWi8 concept

2009 Vision EfficientDynamics BMWi8 concept

2010 5 Series Concept ActiveHybrid

2010 Concept Gran Coupe Previewed the F14 6 series Gran Coupe

2010 Concept 6 Series Coupe Previewed the F12 / F13 6 Series Coupe and Convertible

2010 Vision ConnectedDrive Previewed future BMW communications technology

2010 Vision ConnectedDrive Previewed future BMW communications technology

2011 328 Hommage

2011 i3 Concept Previewed the i3 premium compact electric vehicle

2011 i3 Concept Previewed the i3 premium compact electric vehicle

2011 i8 Concept Previewed the future production i8 plug-in hybrid electric sports car

2012 M135i Concept Previewed the M Performance variant of the F20 1-Series hatchback

2012 Zagato Coupe

2012 Zagato Roadster

2012 Concept Active Tourer Previewed future FWD BMW vehicle architecture and the new 2-Series Gran Turismo

2012 i3 Concept Coupe Previewed a potential coupe version of the future production i3 premium compact electric vehicle

2012 i8 Concept Spyder Previewed a potential spyder version of the future production i8 plug-in hybrid electric sports car

2013 BMW Concept X4 Previewed the F26 X4 Sports Activity Coupe

2013 Concept 4 Series Coupe Previewed the F32 4-Series Coupe

2013 BMW Pininfarina Gran Lusso Coupe

2013 BMW Concept M4 Previewed the F82 M4 and F80 M3

2013 BMW Concept X5 eDrive Previewed the future F15 X5 plug-in hybrid

2014 Vision Future Luxury Concept Previewed the G11 7-Series and potential 9-Series flagship

M models

Production series codes

BMW 501 — (1952–1958) 6 cylinder Limousine

BMW 501 — (1952–1958) 6 cylinder Limousine

BMW 502 — (1954–1964) 8 cylinder Limousine

BMW 502 — (1954–1964) 8 cylinder Limousine

BMW 503 — (1956–1959) 8 cylinder Coupe and Cabriolet

BMW 503 — (1956–1959) 8 cylinder Coupe and Cabriolet

BMW 507 — (1955–1959) 8 cylinder Roadster

BMW 507 — (1955–1959) 8 cylinder Roadster

BMW 3200 CS — (1956–1959) 8 cylinder Coupe and 1 Cabriolet

BMW 3200 CS — (1956–1959) 8 cylinder Coupe and 1 Cabriolet

BMW Typ100 — (1955–1962) Isetta

BMW Typ100 — (1955–1962) Isetta

BMW Typ106 — (1957–1959) 600

BMW Typ106 — (1957–1959) 600

bmw-700

BMW Typ110 – (1961–1964) 700 Cabriolet

BMW Typ110 – (1961–1964) 700 Cabriolet

BMW Typ114 — (1966–1976) 1600-2, 1602-2002TI, 1502

BMW Typ115 — (1963–1964) 1500

BMW Typ115 — (1963–1964) 1500

BMW Typ118 — (1963–1971) 1800-1800TI/SA

BMW Typ118 — (1963–1971) 1800-1800TI/SA

BMW Typ120 — (1966–1970) New Class Coupe 2000C/CS

BMW Typ121 — (1966–1972) 2000-2000tii

BMW Typ121 — (1966–1972) 2000-2000tii

BMW E3 — (1968–1977) 2.5, 2.8, 3.0, 3.3 “New Six” Sedans

BMW E3 — (1968–1977) 2.5, 2.8, 3.0, 3.3 “New Six” Sedans

BMW E9 — (1969–1975) 2800CS, 3.0CS, 3.0CSL “New Six” Coupes

BMW E9 — (1969–1975) 2800CS, 3.0CS, 3.0CSL “New Six” Coupes

BMW M535i M5— (1974–1981) 5 Series Sedan/M535i Sedan

BMW M535i M5— (1974–1981) 5 Series Sedan/M535i Sedan

BMW E21 — (1976–1983) 3 Series Sedan/Convertible

BMW E21 — (1976–1983) 3 Series Sedan/Convertible

BMW E23 — (1977–1986) 7 Series Sedan

BMW E23 — (1977–1986) 7 Series Sedan

BMW M635i — (1976–1989) 6 Series Coupe/M635i Coupe

BMW M635i — (1976–1989) 6 Series Coupe/M635i Coupe

BMW E26 — (1978–1981) M1 Coupe

BMW E26 — (1978–1981) M1 Coupe

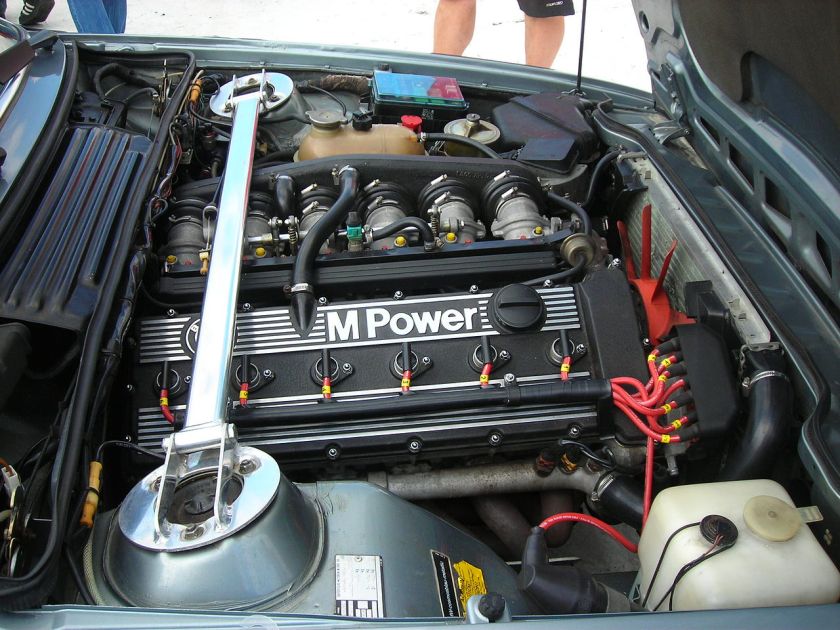

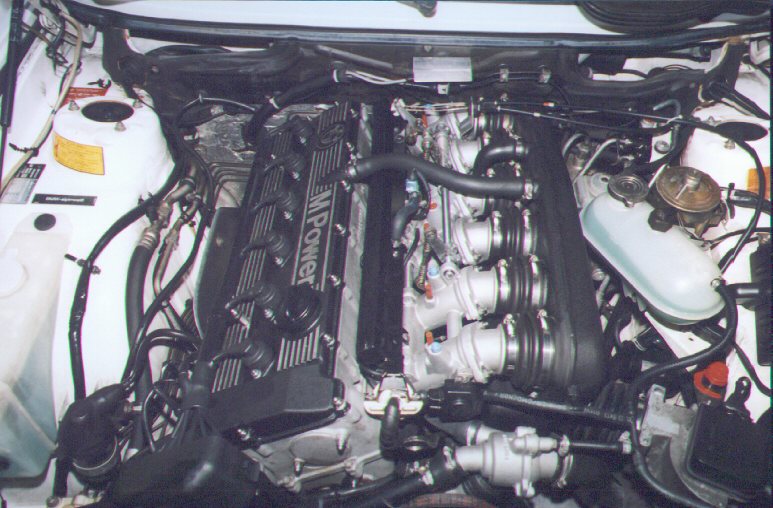

BMW M5 E28 — (1981–1987) 5 Series Sedan/M5 Sedan

BMW M3 E30 — (1983–1991) 3 Series Sedan/Coupe/Touring/Convertible/M3 Coupe/Convertible

BMW M3 E30 — (1983–1991) 3 Series Sedan/Coupe/Touring/Convertible/M3 Coupe/Convertible

BMW Z1 — (1988–1991) Z1 Roadster

BMW E31 — (1989–1999) 8 Series Coupe

BMW E32 — (1986–1994) 7 Series Sedan

BMW E32 — (1987–1994) 7 Series Sedan long wheelbase

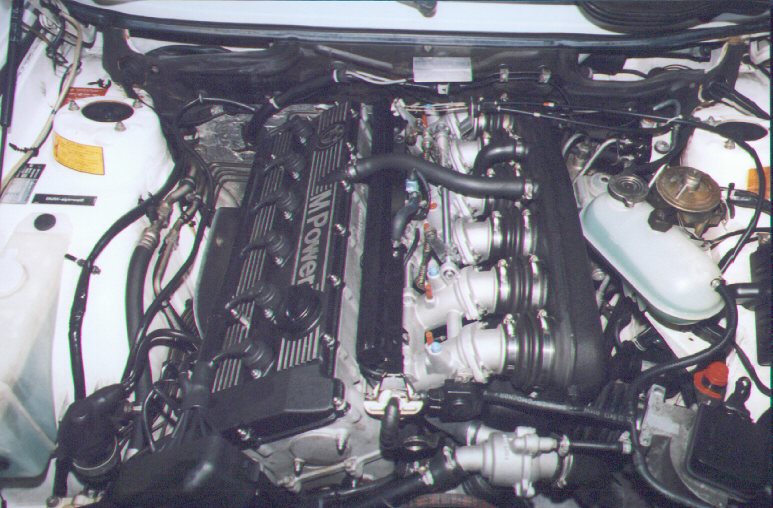

BMW M5 E34 — (1988–1995) 5 Series Sedan/M5 Sedan

BMW E34 — (1991–1996) 5 Series Touring

BMW M3 E36 — (1991–1999) 3 Series Coupe/M3 Coupe

BMW E36 — (1994–1999) 3 Series Touring

BMW M3 E36 — (1991–1999) 3 Series Sedan/M3 Sedan

BMW M3 E36 — (1993–1999) 3 Series Convertible/M3 Convertible

E36/5 — (1994–2000) 3 Series Compact

BMW M Roadster E36/7 — (1995–2002) Z3 Roadster/Z3 M Roadster

BMW M Coupe E36/8 — (1997–2002) Z3 Coupe/Z3 M Coupe

BMW E38 — (1994–2001) 7 Series Sedan

BMW E38 — (1994–2001) 7 Series Sedan

BMW E38/2 — (1994–2001) 7 Series Sedan long wheelbase

BMW E38/3 — (1998–2001) 7 Series Sedan Protection

BMW M5 E39 — (1995–2003) 5 Series Sedan/M5 Sedan

BMW E39/2 — (1996–2003) 5 Series Touring

BMW M3 E46 — (1999–2006) 3 Series Coupe/M3 Coupe

BMW E46 — (1999–2006) 3 Series Touring

BMW E46 — (1998–2006) 3 Series Sedan

BMW E46/5 — (2000–2004) 3 Series Compact

BMW M3 E46 — (1999–2006) 3 Series Convertible/M3 Convertible

BMW E52 — (1999–2003) Z8 Roadster

BMW E52 — (1999–2003) Z8 Roadster

BMW E53 — (1999–2006) X5 Sport Activity Vehicle

BMW E53 — (1999–2006) X5 Sport Activity Vehicle

BMW M5 E60 — (2003–2010) 5 Series Sedan/M5 Sedan

BMW M5 E61 — (2003–2007) 5 Series Touring/M5 Touring

BMW M6 E63 — (2003–2010) 6 Series Coupe/M6 Coupe

BMW M6 E64 — (2003–2010) 6 Series Convertible/M6 Convertible

BMW E65 — (2001–2007) 7 Series short wheelbase

BMW E65 — (2001–2007) 7 Series short wheelbase

BMW E66 — (2001–2007) 7 Series long wheelbase

BMW E67 — (2001–2007) 7 Series Protection

BMW E68 — (2005–2007) Hydrogen 7

BMW X5 M — (2007–2013) X5 Sports Activity Vehicle/X5 M Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW X6 M — (2008–present) X6 Sports Activity Coupe/X6 M Sports Activity Coupe

BMW E72 — (2009–2011) X6 Hybrid Sports Activity Coupe

BMW E81 — (2007–2012) 1 Series Hatchback 3-door

BMW E81 — (2007–2012) 1 Series Hatchback 3-door

BMW 1M Coupe — (2007–2013) 1 Series Coupe/1M Coupe

BMW E83 — (2004–2012) X3 Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW E84 — (2009–present) X1 Compact Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW M Roadster E85 — (2002–2008) Z4 Roadster/Z4 M Roadster

BMW M Coupe E86 — (2006–2008) Z4 Coupe/Z4 M Coupe

BMW E87 — (2004–2011) 1 Series Hatchback 5-door

BMW E88 — (2008–2013) 1 Series Convertible

BMW E89 — (2009–present) Z4 Roadster

BMW M3 E90 — (2005–2011) 3 Series Sedan/M3 Sedan

BMW E91 — (2005–2011) 3 Series Touring

BMW M3 E92 — (2006–2013) 3 Series Coupe/M3 Coupe

BMW M3 E93 — (2007–2013) 3 Series Convertible/M3 Convertible

BMW F01 — (2008–present) 7 Series

BMW F01 — (2008–present) 7 Series

BMW F02 — (2009–present) 7 Series long wheelbase

BMW F03 — (2008–present) 7 Series Protection

BMW F04 — (2011–present) 7 Series ActiveHybrid

BMW M6 F06 — (2011–present) 6 Series Gran Coupe/M6 Gran Coupe

BMW F07 — (2009–present) 5 Series Gran Turismo

BMW M5 F10 — (2011–present) 5 Series Sedan/M5 Sedan

BMW F11 — (2012–present) 5 Series Touring

BMW M6 F12 — (2011–present) 6 Series Coupe/M6 Coupe

BMW M6 F13 — (2011–present) 6 Series Convertible/M6 Convertible

BMW F15 — (2013–present) X5 Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW F16 — (2014) X6 Sports Activity Coupe

BMW F18 — (2010–present) 5 Series long wheelbase

BMW F20 — (2011–present) 1 Series Hatchback 5-door

BMW F21 — (2012–present) 1 Series Hatchback 3-door

BMW F22 — (2013–present) 2 Series Coupe

BMW F23 — (2014) 2 Series Convertible

BMW F25 — (2010–present) X3 Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW F26 — (2014–present) X4 Sports Activity Coupe

BMW F30 — (2012–present) — 3 Series Sedan

BMW F31 — (2012–present) 3 Series Touring

BMW F32 — (2013–present) 4 Series Coupe

BMW F33 — (2013–present) 4 Series Convertible

BMW F34 — (2013–present) 3 Series Gran Turismo

BMW F35 — (2012–present) 3 Series long wheelbase

BMW F36 — (2014) 4 Series Gran Coupe

BMW F45 — (2014) 2 Series Active Tourer

BMW F46 — (2014) 2 Series 7 Seat Gran Tourer

BMW F47 — (2017) X2 Compact Sports Activity Coupe

BMW F48 — (2015) X1 Compact Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW F49 — (2015) X1 7 Seat Compact Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW F52 — (2015–present) 1 Series Sedan

BMW F80 — (2014–present) M3 Sedan

BMW F82 — (2014–present) M4 Coupe

BMW F83 — (2014–present) M4 Convertible

BMW F85 — (2015) X5 M Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW F86 — (2015) X6 M Sports Activity Coupe

BMW F87 — (2015) M2 Coupe

BMW G01 — (2017) X3 Sports Activity Vehicle

BMW G11 740 — (2016) 7 Series short wheelbase

BMW G12 — (2016) 7 Series long wheelbase

BMW G30 — (2016) 5 Series

BMW i

Model nomenclature

Since 1972, BMW model names have generally been a 3 digit number followed by 1, 2 or 3 letters

- the first digit represents the chassis type (e.g. 3 series, 5 series)

- the last two digits represent the engine displacement in litres times 10.

- the letters provide additional information on the model variant (see below).

Commonly used letters at the end of the model name are:

- C = coupé, last used on the BMW E46 and the BMW E63 (dropped after 2005 model year)

- c = cabriolet

- d = diesel

- e = eta, an engine tuned for fuel efficiency rather than power (from the Greek letter ‘η’)

- h = hydrogen

- i = injected (fuel injection)

- L = long wheelbase

- s = sport, this can represent either upgraded interior/cosmetic options or increased engine power depending on the model. For the E36 range, all models with “s” in the name were coupes/convertibles)

- sDrive = rear wheel drive

- T = touring (wagon/estate)

- t = hatchback for the BMW 3 Series hatchback

- td = “Turbo Diesel” ( 524td, 525td/s, 324td, 325td/s, 318tds), or hatchback diesel ( E46Compact 318td, 320td; E36Compact 318tds)

- x / xDrive = BMW xDriveall wheel drive

For example, the BMW 760iL is a fuel-injected 7 Series with a long wheelbase and 6.0 liters of displacement. A 318i represents a 3 series with a 1.8 L engine, in this case the “i” means that the engine is fuel-injected. This badge was used for successive generations, E65 and F01.

When ‘L’ supersedes the series number (e.g. L6, L7, etc.) it identifies the vehicle as a special luxury variant, featuring extended leather and special interior appointments. The L7 is based on the E23 and E38, and the L6 is based on the E24.

When ‘X’ is capitalized and supersedes the series number (e.g. X3, X5, etc.) it identifies the vehicle as one of BMW’s Sports Activity Vehicles (SAV), their brand of crossovers. Predominantly these vehicles feature BMW’s xDrive, though both the E84 X1 and the F15 X5 offer rear wheel drive, badged as sDrive vehicles. The second number in the ‘X’ series denotes the platform that it is based upon, for instance the X5 is derived from the 5 Series. Unlike BMW cars, the SAV’s main badge does not denote engine size, the engine is instead indicated on side badges.

The ‘Z’ identifies the vehicle as a two-seat roadster (e.g. Z1, Z3, Z4, etc.). ‘M’ variants of ‘Z’ models have the ‘M’ as a suffix or prefix, depending on country of sale (e.g. ‘Z4 M’ is ‘M Roadster’ in Canada).

Previous X & Z vehicles had ‘i’ or ‘si’ following the engine displacement number (denoted in liters). BMW is now globally standardizing this nomenclature on X & Z vehicles by using ‘sDrive’ or ‘xDrive’ (simply meaning rear or all wheel drive, respectively) followed by two numbers which vaguely represent the vehicle’s engine (e.g. Z4 sDrive35i is a rear wheel drive Z4 roadster with a 3.0 L twin-turbo fuel-injected engine).

The ‘s’ code has meant different things at different times. The E30 325iS was an options pack for the 325i, however the E30/E36 318iS models used different engines to E30/E36 318i models. The ‘s’ code was dropped in 1999 after the 325tds model (the last use in North America was for the 1995 325is). However, the ‘s’ code was revived on the 2011 model year BMW 335is and BMW Z4 sDrive35is. The 335is has a more powerful engine, sports options and an optional dual clutch transmission that slots between the regular 335i and top-of-the-line M3.

The ‘M’ – for Motorsport – identifies the vehicle as a high-performance model of a particular series (e.g. M3, M5, M6, etc.). For example, the M6 is the highest performing vehicle in the 6 Series lineup. Although ‘M’ cars should be separated into their respective series platforms, it is very common to see ‘M’ cars grouped together as its own lineup on the official BMW website.

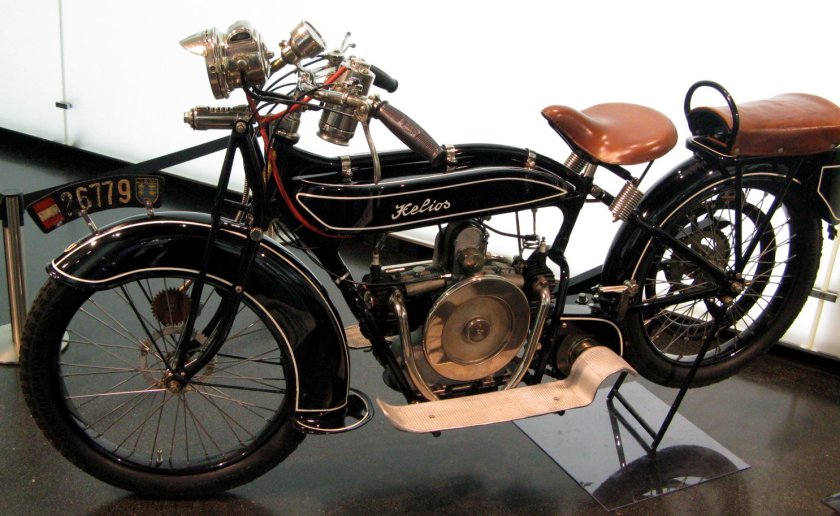

A similar nomenclature is used by BMW Motorrad for their motorcycles.

Exceptions

There are exceptions to the numbering nomenclature, most commonly relating to SUV models, turbocharged engines and differing specification despite the same engine capacity.

SUV models

The M versions of the X5 M and X6 M, could not follow the regular naming convention, since “MX5” was used for Mazda‘s MX-5 Miata and MX-6.

Turbocharged engines

The 2008 BMW 335i and 535i also have 3.0-liter engine; however the engines are twin-turbocharged (N54) which is not identified by the nomenclature. Nonetheless the ’35’ indicates a more powerful engine than previous ’30’ models that have the naturally aspirated N52 engine. The 2011 BMW 740i and 335is share the same twin-turbo 3.0 N54 engine, although the badging is not consistent (’40’ and ‘s’). Due to the move to turbocharged engines, the 2009 750i has a 4.4 L turbocharged engine, compared with a 4.8 L naturally-aspirated engine for the 2006 750i.

Due to the increased use of turbocharging recently, it will become increasingly common for the last two digits to not represent the engine capacity (for example the F30 328i uses a turbocharged 2.0-litre engine).

Different specification levels but same engine capacity

In the 2008 model year, the BMW 125i, 128i, 328i, and 528i all had 3.0 naturally aspirated engines (N52), not a 2,500 cc or 2,800 cc engine as the series designation number would lead one to believe. The ’28’ is to denote a detuned engine in the 2008 cars, compared to the 2006 model year ’30’ vehicles (330i and 530i) whose 3.0 L naturally aspirated engines are from the same N52 family but had more output.

A similar situation occurred with the E36/E46 323i and E39 523i models. These models all used 2.5-litre engines. However, the previous 325i and 525i models were higher in the model range than their replacements, therefore the replacements were called 323i and 523i (which also provided a bigger gap to the future 328i and 528i models). BMW has not produced a 2.3-litre gasoline engine since the early 1990s.

The opposite situation occurred with the 1996 E36 318i, since it used a 1.9 L engine (M44) as opposed to the 1.8 L (M42) used in the 1992 to 1995 models. This was done to avoid changing the model code for the base model (i.e. otherwise consumers would need to be taught that the base model was now called 319i).

Another example of an exception is the 1980s 325e and 525e models. These cars actually used 2.7-litre engines (which were tuned for fuel economy rather than power).

Gallery

Motorcycles

BMW Motorrad has produced motorcycles bearing the BMW name since the introduction of the BMW R32 in 1923. Prior to that date it produced engines for other manufacturers’ motorcycles.

Present day

- BMW F650GS & F800GS

- BMW F800R

- BMW F800S

- BMW F800ST

- BMW G450X

- BMW G650 Xmoto, Xchallenge, and Xcountry

- BMW R1200GS

- BMW R1200R

- BMW R1200RT

- BMW R1200S

- BMW K1200LT

- BMW K1300GT

- BMW K1300R

- BMW K1300S

- BMW K1600GT and K1600GTL

- BMW S1000RR

See also

References

- Jump up^ Lewin, Tony (2004), The Complete Book Of BMW: Every Model Since 1950, MotorBooks International, p. 307, ISBN 978-0-7603-1951-2, retrieved 2011-04-28

- Jump up^ Zoellter, Juergen (June 2009), “BMW E1 Concept – Car News; Electric Car, Take Two.”, Car and Driver, retrieved 2011-04-28

- Jump up^ “Concept Cars; Diminutive BMW”, Popular Science (Bonnier Corporation) 243 (1), July 1993: 37, ISSN 0161-7370, retrieved 2011-04-28

- ^ Jump up to:a b “BMW-Zukunft der Vergangenheit”, de:Motor Klassik (in German) (de:Motor Presse Stuttgart), 18 April 2011, retrieved 2011-04-28

- Jump up^ “BMW Just 4/2”, Popular Science (Bonnier Corporation) 248 (1), January 1996: 14, ISSN 0161-7370, retrieved 2011-04-28

- Jump up^ Greg Migliore (2008-06-10). “Future vision? BMW reveals fabric-skinned concept after six years”. http://www.autoweek.com. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- Jump up^ W.P. BMW Group Canada Inc. http://www.bmw.ca

- Jump up^ FAQ from the BMW Z4 Press Conference, as reported by BMWBLOG, May 8, 2009. http://www.bmwblog.com/2009/05/08/faq-from-the-recent-bmw-press-conference

- Jump up^ “Preview: 2011 BMW 335is Coupe – Posted Driving”. Network.nationalpost.com. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- Jump up^ Cunningham, Wayne (2010-07-13). “2011 BMW 335is (photos) – CNET Reviews”. Reviews.cnet.com. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- Jump up^ Carver, Robert. BMW San Antonio. BMW Information http://www.mrbimmer.com/bmw.information

New Class

The New Class (German: Neue Klasse) was a line of compact sedans and coupes starting with the 1962 1500 and continuing through the last 2002s in 1977. Powered by BMW’s celebrated four-cylinder M10 engine, the New Class models had a fully independent suspension, MacPherson struts in front, and front disc brakes. Initially a family of four-door sedans and two-door coupes, the New Class line was broadened to two-door sports sedans with the addition of the 02 Series 1600 and 2002 in 1966.

Sharing little in common with the rest of the line beyond power train, the sporty siblings caught auto enthusiasts’ attention and established BMW as an international brand. Precursors to the famed BMW 3 Series, the two-doors’ success cemented the firm’s future as an upper tier performance car maker. New Class four-doors with numbers ending in “0” were replaced by the larger BMW 5 Series in 1972. The upscale 2000C and 2000CS coupes were replaced by the six-cylinder BMW E9, introduced in 1969 with the 2800CS. The 1600 two-door was discontinued in 1975, and the 2002 was replaced by the 320i in 1975.

Current models

The 1 Series, originally launched in 2004, is BMW’s smallest car. Currently available are the second generation hatchback (F20) and first generation coupe/convertible (E82/E88). The 3 Series, a compact executive carmanufactured since model year 1975, is currently in its sixth generation (F30); models include the sport sedan (F30), and fourth generation station wagon (F30), and convertible (E93), and the Gran Turismo. In 2014, the 4 Series has been released and replaced the 3 Series Coupe and Convertible. The 5 Series is a mid-size executive car, available in sedan (F10) and station wagon (F11) forms. The 5 Series Gran Turismo (F07), which debuted in 2010, created a segment between station wagons and crossover SUV.  BMW Z4 (E89)

BMW Z4 (E89)

BMW’s full-size flagship executive sedan is the 7 Series. Typically, BMW introduces many of their innovations first in the 7 Series, such as the iDrive system. The 7 Series Hydrogen, having one of the world’s first hydrogenfueled internal combustion engines, is fueled by liquid hydrogen and emits only clean water vapor. The latest generation (F01) debuted in 2009. Based on the 5 Series’ platform, the 6 Series is BMW’s grand touring luxury sport coupe/convertible (F12/F13). A 2-seater roadster and coupe which succeeded the Z3, the Z4 has been sold since 2002.

The X3 (F25), BMW’s second crossover SUV (called SAV or “Sports Activity Vehicle” by BMW) debuted in 2010 and replaced the X3 (E83), which was based on the E46 3 Series’ platform, and had been in production since 2003. Marketed in Europe as an off-roader, it benefits from BMW’s xDrive all-wheel drive system. The all-wheel drive X5 (E53) was BMW’s first crossover SUV (SAV), based on the 5 Series, and is a mid-size luxury SUV (SAV) sold by BMW since 2000. A 4-seat crossover SUV released by BMW in December 2007, the X6 is marketed as a “Sports Activity Coupe” (SAC) by BMW. The X1 extends the BMW Sports Activity Series model lineup.

The BMW i is a sub-brand of BMW founded in 2011 to design and manufacture plug-in electric vehicles. The sub-brand initial plans called for the release of two vehicles; series production of the BMW i3 all-electric car began in September 2013, and the market launch took place in November 2013 with the first retail deliveries in Germany. The BMW i8 sports plug-in hybrid car was launched in Germany in June 2014. As of June 2015, over 30,000 i brand vehicles have been sold worldwide since 2013, consisting of over 26,000 i3s and about 4,500 i8s. The all-electric BMW i3 ranked among the world’s top ten best selling plug-in electric vehicles as of May 2015.

- 1 Series (F20) (2011–present) 5-door Hatchback

- 1 Series (F21) (2011–present) 3-door Hatchback

- 2 Series (F22) (2014–present) Coupe and convertible

- 2 Series Active Tourer (F45) (2014–present) Compact MPV

- 3 Series (F30) (2012–present) Sedan and wagon

- 4 Series (F32/F33/F36) (2014–present) Coupe and convertible

- 5 Series (F10/F11) (2009–present) Sedan and wagon

- 6 Series (F12) (2010–present) Coupe, convertible, Gran Coupe

- 7 Series (F01) (2008–present) Sedan

- 3 Series Gran Turismo (2013–present) Progressive Activity Sedan

- 5 Series Gran Turismo (2009–present) Progressive Activity Sedan

- BMW i3 (2013–present) all-electric car

- BMW i8 (2014–present) plug-in hybrid sports car

- X1 (E84) (2009–present) Compact Crossover SUV/Sports Activity Vehicle (SAV)

- X3 (F25) (2010–present) Compact Crossover SUV/Sports Activity Vehicle (SAV)

- X4 (F25) (2014–present Sports Activity Coupe

- X5 (F15) (2014–present) Mid-Size Crossover SUV/Sports Activity Vehicle (SAV)

- X6 (F16) (2014–present) Sports Activity Coupe

- Z4 (E89) (2009–present) Sports Roadster

M models

BMW produce a number of high-performance derivatives of their cars developed by their BMW M GmbH (previously BMW Motorsport GmbH) subsidiary.

The current M models are:

- M3 – F80 Sedan (2013 to present)

- M4 – F82 Coupé/F83 Convertible (2013 to present)

- M5 – F10 Saloon (2011 to present)

- M6 – F06 Gran Coupé/F12 Convertible/F13 Coupé (2012 to present)

- X5 M – F15 SAV (2014 to present)

- X6 M – F16 SAV (2014 to present)

Motorsport

BMW has been engaged in motorsport activities since the dawn of the first BMW motorcycle in 1923.

Motorsport sponsoring

- Formula BMW – A Junior racing Formula category.

- Kumho BMW Championship – A BMW-exclusive championship run in the United Kingdom.

Motorcycle

- Isle of Man TT – Georg ‘Schorsch’ Meier won the 1939 running of the Grand Prix and Michael Dunlop won both the 2014 Senior and Superbike races on a 2014 BMW S1000RR.

- Dakar Rally – BMW motorcycles have won the Dakar rally six times. In 1981, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1999, and 2000.

- Superbike World Championship – BMW returned to premier road racing in 2009 with their all new superbike, the BMW S1000RR.

Formula One – F1

BMW has a history of success in Formula One. BMW powered cars have won 20 races. In 2006 BMW took over the Sauber team and became Formula One constructors. In 2007 and 2008 the team enjoyed some success. The most recent win is a lone constructor team’s victory by BMW Sauber F1 Team, on 8 June 2008, at the Canadian Grand Prix with Robert Kubica driving. Achievements include:

- Driver championship: 1 (1983)

- Constructor championship: 0 (Runner-up 2002, 2003, 2007)

- Fastest laps: 33

- Grand Prix wins: 20

- Podium finishes: 76

- Pole positions: 33

BMW was an engine supplier to Williams, Benetton, Brabham, and Arrows. Notable drivers who have started their Formula One careers with BMW include Jenson Button, Juan Pablo Montoya, Robert Kubica and Sebastian Vettel.

In July 2009, BMW announced that it would withdraw from Formula One at the end of the 2009 season. The team was sold back to the previous owner, Peter Sauber, who kept the BMW part of the name for the 2010 season due to issues with the Concorde Agreement. The team has since dropped BMW from their name starting in 2011.

Sport cars

- Le Mans 24 Hours – BMW won Le Mans in 1999 with the BMW V12 LMR designed by Williams Grand Prix Engineering. Also the Kokusai Kaihatsu Racing team won the 1995 edition with a BMW-engined McLaren F1 GTRrace car.

- Nürburgring – BMW won the 24 Hours Nürburgring 19 times and the 1000km Nürburgring twice (1976 and 1981).

- 24 Hours of Daytona – BMW won three times (1976, 2011, 2013)

- Spa 24 Hours – BMW won 21 times

- A BMW works team E36 320d was the first diesel-powered overall winner ever at the 24 Hours Nürburgring.

- McLaren F1 GTR – Successful mid-1990s GT racing car with a BMW designed engine. It won the BPR Global GT Series in 1995 and 1996 and the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1995.

- American Le Mans Series – BMW has won three (2001, 2010, 2011) GT Team Championships and GT Automobile Manufacturer titles. Twice (2010, 2011) with Team RLL in the Crowne Plaza V8 powered M3 GT coupe and once (2001) with the BMW Motorsport team in the V8 powered M3 GTR.

Touring cars

BMW has a long and successful history in touring car racing.

- British Touring Car Championship (BTCC) – BMW won the drivers’ championship in 1988, 1991, 1992 and 1993 and manufacturers’ championship in 1991 and 1993.

- The DRM (Deutsche Rennsport Meisterschaft) was won by Harald Ertl in a BMW 320i Turbo in 1978

- DTM (Deutsche Tourenwagen Meisterschaft) – the following won the DTM drivers’ championship driving BMWs:

- 1987: Eric van der Poele, BMW M3

- 1989: Roberto Ravaglia, BMW M3

- 2012: Bruno Spengler, BMW M3 DTM

- European Touring Car Championship (ETCC) – Since 1968, BMW won 24 drivers’ championships along with several manufacturers’ and teams’ titles.

- Japanese Touring Car Championship (JTCC) – BMW (Schnitzer) flew from Europe to Japan to compete in the JTCC and won the championship in 1995.

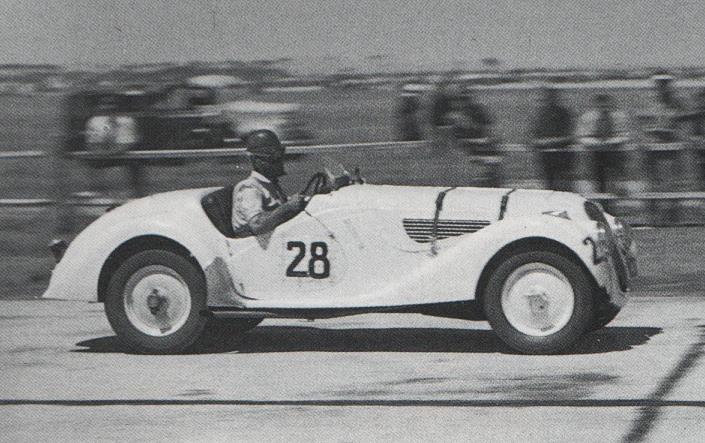

- Mille Miglia – BMW won the 1940 Brescia Grand Prix with a 328 Touring Coupé. Previously in 1938 the 328 sport car won the Mille Miglia 2000 litre class.

- SCCA Pro Racing World Challenge Touring Car Series(WC) – BMW won the manufacturer’s championship in 2001 and Bill Auberlen, driving a Turner Motorsport BMW 325i, won the 2003 and 2004 Driver’s Championships.

- World Touring Car Championship (WTCC) – BMW won four drivers’ championship (1987, 2005, 2006 and 2007) and three manufacturers’ titles (2005–2007).

BMW announced on 15 October 2010 that it will return to touring car racing during the 2012 season. Dr. Klaus Draeger, director of research and development of the BMW Group, who was in charge of the return to DTM racing (Deutsche Tourenwagen Masters), commented that “The return of BMW to the DTM is a fundamental part of the restructuring of our motorsport activities. With its increased commitment to production car racing, BMW is returning to its roots. The race track is the perfect place to demonstrate the impressive sporting characteristics of our vehicles against our core competitors in a high-powered environment. The DTM is the ideal stage on which to do this.”

Rally

- RAC Rally – The 328 sport car won this event in 1939.

- Paris Dakar Rally – BMW motorcycles have won this event 6 times total including 1981, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1999, 2000.

- Tour de Corse – The BMW M3 – E30 won this event in 1987.

Sponsorships

In football, BMW sponsors Bundesliga club Eintracht Frankfurt.

It was an official sponsor of the London 2012 olympics providing 4000 BMWs and Minis in a deal made in November 2009. The company also made a six-year sponsorship deal with the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) in July 2010.

BMW has sponsored various European golf events such as the PGA Championship at Wentworth, the BMW Italian Open and the BMW International Open in Germany.

In 2012, BMW Australia announced a 2-year sponsorship agreement with the Australian Film Institute’s Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA) Awards. As part of the agreement, BMW supplied a fleet of vehicles renowned for appearing in feature films. The vehicles supplied included a range of elegant BMW limousines, iconic BMW’s of the past and the BMW 6 Series which featured in Mission Impossible 4: Ghost Protocol.

Environmental record

The company is a charter member of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency‘s (EPA) National Environmental Achievement Track, which recognizes companies for their environmental stewardship and performance. It is also a member of the South Carolina Environmental Excellence Program.

In 2012, BMW was named the world’s most sustainable automotive company for the eighth consecutive year by the Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes. The BMW Group is the only automotive enterprise in the index since its inception in 1999. In 2001, the BMW Group committed itself to the United Nations Environment Programme, the UN Global Compact and the Cleaner Production Declaration. It was also the first company in the automotive industry to appoint an environmental officer, in 1973. BMW is a member of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

BMW is industry leader in the Carbon Disclosure Project’s Global 500 ranking and 3rd place in Carbon Disclosure Leadership Index across all industries. BMW is listed in the FTSE4GoodIndex. The BMW Group was rated the most sustainable DAX 30 company by Sustainalytics in 2012.

BMW has taken measures to reduce the impact the company has on the environment. It is trying to design less-polluting cars by making existing models more efficient, as well as developing environmentally friendly fuels for future vehicles. Possibilities include: electric power, hybrid power (combustion engines and electric motors) hydrogen engines.

BMW offers 49 models with EU5/6 emissions norm and nearly 20 models with CO2 output less than 140 g/km, which puts it on the lowest tax group and therefore could provide the future owner with eco-bonus offered from some European countries.

However, there have been some criticisms directed at BMW, and in particular, accusations of greenwash in reference to their BMW Hydrogen 7. Some critics claim that the emissions produced during hydrogen fuel production outweigh the reduction of tailpipe emissions, and that the Hydrogen 7 is a distraction from more immediate, practical solutions for car pollution. The BBC’s Jorn Madslien questioned whether the Hydrogen 7 was “a truly green initiative or merely a cynical marketing ploy”

Bicycles

BMW has created a range of high-end bicycles sold online and through dealerships. They range from the Kid’s Bike to the EUR 4,499 Enduro Bike. In the United States, only the Cruise Bike and Kid’s Bike models are sold.

BMW nomenclature

BMW vehicles follow a certain nomenclature; usually a 3 digit number is followed by 1 or 2 letters. The first number represents the series number. The next two numbers traditionally represent the engine displacement in cubic centimeters divided by 100. However, more recent cars use those two numbers as a performance index, as e.g. the 116i, 118i and 120i (all 2,0L petrol-powered), just like the 325d and 330d (both 3,0L diesel) share the same motor block while adjusting engine power through setup and turbocharging. A similar nomenclature is used by BMW Motorrad for their motorcycles.

The system of letters can be used in combination, and is as follows:

- A = automatic transmission

- C = coupé, last used on the BMW E46 and the BMW E63 (dropped after 2005 model year)

- c = cabriolet

- d = diesel†

- e = eta (efficient economy, from the Greek letter ‘η’)

- g = compressed natural gas/CNG

- h = hydrogen

- i = fuel-injected

- L = long wheelbase

- M = Motorsport

- s = sport, also means “2 dr” on E36 model††

- sDrive = rear-wheel drive

- T = touring (wagon/estate)

- Ti = hatchback for the BMW 3 Series hatchback

- x / xDrive = BMW xDrive all-wheel drive

† historic nomenclature indicating “td” refers to “Turbo Diesel”, not a diesel hatchback or touring model (524td, 525td)

†† typically includes sport seats, spoiler, aerodynamic body kit, upgraded wheels and Limit Slip Differential on pre-95 model etc.

For example, the BMW 750iL is a fuel-injected 7 Series with a long wheelbase and 5.4 litres of displacement. This badge was used for successive generations, E65 and F01, except the “i” and “L” switched places, so it read “Li” instead of “iL”.

When ‘L’ supersedes the series number (e.g. L6, L7, etc.) it identifies the vehicle as a special luxury variant, having extended leather and special interior appointments. The L7 is based on the E23 and E38, and the L6 is based on the E24.

When ‘X’ is capitalised and supersedes the series number (e.g. X3, X5, etc.) it identifies the vehicle as one of BMW’s Sports Activity Vehicles (SAV), their brand of crossovers, with BMW’s xDrive. The second number in the ‘X’ series denotes the platform that it is based upon, for instance the X5 is derived from the 5 Series. Unlike BMW cars, the SAV’s main badge does not denote engine size; the engine is instead indicated on side badges.

The ‘Z’ identifies the vehicle as a two-seat roadster (e.g. Z1, Z3, Z4, etc.). ‘M’ variants of ‘Z’ models have the ‘M’ as a suffix or prefix, depending on country of sale (e.g. ‘Z4 M’ is ‘M Roadster’ in Canada).

Previous X & Z vehicles had ‘i’ or ‘si’ following the engine displacement number (denoted in litres). BMW is now globally standardising this nomenclature on X & Z vehicles by using ‘sDrive’ or ‘xDrive’ (simply meaning rear or all-wheel drive, respectively) followed by two numbers which vaguely represent the vehicle’s engine (e.g. Z4 sDrive35i is a rear-wheel-drive Z4 roadster with a 3.0 L twin-turbo fuel-injected engine).

BMW last used the ‘s’ for the E36 328is, which ceased production in 1999. However, the ‘s’ nomenclature was brought back on the 2011 model year BMW 335is and BMW Z4 sDrive35is. The 335is is a sport-tuned trim with more performance and an optional dual clutch transmission that slots between the regular 335i and top-of-the-line M3.

The ‘M’ – for Motorsport – identifies the vehicle as a high-performance model of a particular series (e.g. M3, M5, M6, etc.). For example, the M6 is the highest performing vehicle in the 6 Series lineup. Although ‘M’ cars should be separated into their respective series platforms, it is very common to see ‘M’ cars grouped together as its own lineup on the official BMW website.

Exceptions

There are exceptions to the numbering nomenclature.

The M version of the BMW 1 Series was named the BMW 1 Series M Coupe rather than the traditional style “M1” due to the possible confusion with BMW’s former BMW M1 homologation sports car.

The M versions of the Sports Activity Vehicles, such as the X5 M, could not follow the regular naming convention since MX5 was used for Mazda‘s MX-5 Miata.

For instance in the 2008 model year, the BMW 125i/128i, 328i, and 528i all had 3.0 naturally aspirated engines (N52), not a 2,500 cc or 2,800 cc engine as the series designation number would lead one to believe. The ’28’ is to denote a detuned engine in the 2008 cars, compared to the 2006 model year ’30’ vehicles (330i and 530i) whose 3.0 naturally aspirated engines are from the same N52 family but had more output.

The 2008 BMW 335i and 535i also have 3.0-litre engine; however the engines are twin-turbocharged (N54) which is not identified by the nomenclature. Nonetheless the ’35’ indicates a more powerful engine than previous ’30’ models that have the naturally aspirated N52 engine. The 2011 BMW 740i and 335is shares the same twin-turbo 3.0 engine from the N54 family but tuned to higher outputs, although the badging is not consistent (’40’ and ‘s’). The 2013 BMW 640i Gran Coupe’s twin-scroll single turbo 3.0L inline-6 engine makes similar output to the older twin turbo inline-6 engines.

The E36 and E46 323i and E39 523i had 2.5-litre engines. The E36 318i made after 1996 has a 1.9 L engine (M44) as opposed to the 1.8 L (M42) used in the 1992 to 1995 models. The E39 540i had a 4.4 L M62 engine, instead of a 4.0 L as the designation would suggest.

The badging for recent V8 engines (N62 and N63) also does not indicate displacement, as the 2006 750i and 2009 750i have 4800 cc (naturally aspirated) and 4400 cc (twin-turbocharged) engines, respectively.

Carsharing services

In June 2011, BMW and Sixt launched Drivenow, a joint-venture that provides carsharing services in several cities in Europe and North America. As of December 2012, DriveNow operates over 1,000 vehicles, which serve five cities worldwide and over 60,000 customers.

Light and Charge

BMW has developed street lights equipped with sockets to charge electric cars, called Light and Charge.

Community

From the summer of 2001 until October 2005, BMW hosted The Hire, showcasing sporty models being driven to extremes. These videos are still popular within the enthusiast community and proved to be a ground-breaking online advertising campaign.

Annually since 1999, BMW enthusiasts have met in Santa Barbara, CA to attend Bimmerfest. One of the largest brand-specific gatherings in the U.S., over 3,000 people attended in 2006, and over 1,000 BMW cars were present. In 2007, the event was held on 5 May.

BMW slang

The initials BMW are pronounced [ˈbeː ˈɛm ˈveː] in German. The model series are referred to as “Einser” (“One-er” for 1 series), “Dreier” (“Three-er” for 3 series), “Fünfer” (“Five-er” for the 5 series), “Sechser” (“Six-er” for the 6 series), “Siebener” (“Seven-er” for the 7 series). These are not actually slang, but are the normal way that such letters and numbers are pronounced in German.

The English slang terms Beemer, Bimmer and Bee-em are variously used for BMWs of all kinds, cars and motorcycles.

In the US, specialists have been at pains to prescribe that a distinction must be made between using Beemer exclusively to describe BMW motorcycles, and using Bimmer only to refer to BMW cars, in the manner of a “true aficionado” and avoid appearing to be “uninitiated.” The Canadian Globe and Mail prefers Bimmer and calls Beemer a “yuppie abomination,” while the Tacoma News Tribune says it is a distinction made by “auto snobs.” Using the wrong slang risks offending BMW enthusiasts. An editor of Business Week was satisfied in 2003 that the question was resolved in favor of Bimmer by noting that a Google search yielded 10 times as many hits compared to Beemer.

The arts

Manufacturers employ designers for their cars, but BMW has made efforts to gain recognition for exceptional contributions to and support of the arts, including art beyond motor vehicle design. These efforts typically overlap or complement BMW’s marketing and branding campaigns. BMW Headquarters designed in 1972 by Karl Schwanzer has become a European icon, and artist Gerhard Richter created his Red, Yellow, Blue series of paintings for the building’s lobby. In 1975, Alexander Calder was commissioned to paint the 3.0CSL driven by Hervé Poulain at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. This led to more BMW Art Cars, painted by artists including David Hockney, Jenny Holzer, Roy Lichtenstein, and others. The cars, currently numbering 17, have been shown at the Louvre, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, and, in 2009, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and New York’s Grand Central Terminal. BMW was the principal sponsor of the 1998 The Art of the Motorcycle exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and other Guggenheim museums, though the financial relationship between BMW and the Guggenheim was criticised in many quarters.

In 2012, BMW brought out the BMW Art Guide by Independent Collectors, which had, amongst others, the Dikeou Collection. It is the first global guide to private and publicly accessible collections of contemporary art worldwide.

The 2006 “BMW Performance Series” was a marketing event geared to attract black car buyers, and included the “BMW Pop-Jazz Live Series,” a tour headlined by jazz musician Mike Phillips, and the “BMW Blackfilms.com Film Series” highlighting black filmmakers.

April Fools

BMW has garnered a reputation over the years for its April Fools pranks, which are printed in the British press every year. In 2010, they ran an advert announcing that customers would be able to order BMWs with different coloured badges to show their affiliation with the political party they supported.

Overseas subsidiaries

Brazil

On October 9, 2014, BMW’s new South American automobile plant in Araquari, Santa Catarina produced its first car. BMW intend to increase its production capacity to over 30,000 vehicles a year. The new site is intended to create around 1,300 new jobs, of which 500 have already been filled.

Canada

In October 2008, BMW Group Canada was named one of Greater Toronto’s Top Employers by Mediacorp Canada Inc., which was announced by the Toronto Star newspaper.

China

Signing a deal in 2003 for the production of sedans in China, May 2004 saw the opening of a factory in the North-eastern city of Shenyang where Brilliance Auto produces BMW-branded automobiles in a joint venture with the German company.

Egypt

Bavarian Auto Group is a multinational group of companies established in March 2003 when it was appointed as the sole importer of BMW and Mini in Egypt, with monopoly rights for import, assembly, distribution, sales and after-sales support of BMW products in Egypt. Since that date, BAG invested a total amount of US$100 million distributed on seven companies and 11 premises in addition to three stores.

India

BMW India was established in 2006 as a sales subsidiary in Gurgaon (National Capital Region). A state-of-the-art assembly plant for BMW 3 and 5 Series started operation in early 2007 in Chennai. Construction of the plant started in January 2006 with an initial investment of more than one billion Indian Rupees. The plant started operation in the first quarter of 2007 and produces the different variants of BMW 3 Series, BMW 5 Series, BMW 7 Series, BMW X1, BMW X3, Mini Cooper S, Mini Cooper D and Mini Countryman.

Japan

Yanase Co., Ltd. is the exclusive retailer of all imported BMW (passenger cars and motorcycles) products to Japanese consumers, and has had the exclusive rights to do so since the end of World War II.

Mexico

In July 2014 BMW announced it was establishing a plant in Mexico, in the city and state of San Luis Potosi involving an investment of $1 billion. Taking advantage of lower wages in the country, and the terms of free trade agreements Mexico has with a host of other countries, were the motivating factors the company said. The plant will employ 1,500 people, and produce 150,000 cars annually, commencing in 2019.

South Africa

BMWs have been assembled in South Africa since 1968, when Praetor Monteerders’ plant was opened in Rosslyn, near Pretoria. BMW initially bought shares in the company, before fully acquiring it in 1975; in so doing, the company became BMW South Africa, the first wholly owned subsidiary of BMW to be established outside Germany. Three unique models that BMW Motorsport created for the South African market were the E23 M745i (1983), which used the M88 engine from the BMW M1, the BMW 333i (1986), which added a six-cylinder 3.2-litre M30 engine to the E30, and the E30 BMW 325is (1989) which was powered by an Alpina-derived 2.7-litre engine.

Unlike U.S. manufacturers, such as Ford and GM, which divested from the country in the 1980s, BMW retained full ownership of its operations in South Africa. Following the end of apartheid in 1994, and the lowering of import tariffs, BMW South Africa ended local production of the 5-Series and 7-Series, in order to concentrate on production of the 3-Series for the export market. South African–built BMWs are now exported to right hand drive markets including Japan, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Hong Kong, as well as Sub-Saharan Africa. Since 1997, BMW South Africa has produced vehicles in left-hand drive for export to Taiwan, the United States and Iran, as well as South America.

BMWs with a VIN starting with “NC0” are manufactured in South Africa.

United States

BMW Spartanburg factory

The BMW Manufacturing Company opened in 1994 and has been manufacturing all Z4 and X5 models, and more recently the X6 and X3, including those for export to Europe, on the same assembly line in Greer near Spartanburg. In an average work day the company builds 600 vehicles: 500 X5s and 100 Z4s. The engines for these vehicles are built in Munich, Germany. BMWs with a VIN starting with “4US and 5US” are manufactured at Spartanburg.

In 2010 BMW announced that it would spend $750 million to expand operations at the Greer plant. This expansion will allow production of 240,000 vehicles a year and will make the plant the largest car factory in the United States by number of employees. BMW’s largest single market is the United States.

Currently, the facility produces all BMW X3, X4, X5, X5 M, X6 and X6 M models.

Marketing

BMW began using the slogan ‘The Ultimate Driving Machine’ in the 1970s. In 2010, this long-lived campaign was mostly supplanted by ‘Joy’, a campaign intended to make the brand more “approachable” and to better appeal to women, but by 2012 they had returned to “The Ultimate Driving Machine”, which has a strong public association with BMW.

Audio logo

In 2013, BMW replaced the ‘double-gong’ sound used in TV and Radio advertising campaigns since 1998. The new sound, developed to represent the future identity of BMW, was described as “introduced by a rising, resonant sound and underscored by two distinctive bass tones that form the sound logo’s melodic and rhythmic basis.” The new sound was first used in BMW 4 Series Concept Coupe TV commercial. The sound was produced by Thomas Kisser of HASTINGS media music.

Roundel logo

The circular blue and white BMW logo or roundel evolved from the circular Rapp Motorenwerke company logo, from which the BMW company grew, combined with the blue and white colors of the flag of Bavaria. The logo has been portrayed as the movement of an aircraft propeller with the white blades cutting through a blue sky—first used in a BMW advertisement in 1929, twelve years after the roundel was created—but this is not the origin of the logo itself. The colors of the logo stands for the colors from the south part state of Beieren.

Issues

Theft using OBD, 2012

In 2012, BMW vehicles were stolen by programming a blank key fob to start the car through the on-board diagnostics (OBD) connection. The primary causes of this vulnerability lie in the lack of appropriate authentication and authorization in the OBD specifications, which rely largely on security through obscurity.

ConnectedDrive, 2010-2014

Dieter Spaar was asked by ADAC to analyze ConnectedDrive and its hardware called Combox. He uncovered the following problems which allowed him e.g. to remotely open the car:

- BMW uses the same symmetric keys in all cars.

- some services do not encrypt transported data while connecting to the BMW backend.

- the integrity of the ConnectedDrive configuration is not protected.

- the Combox discloses the vehicle identification number via NGTP (next generation telematics pattern) error messages.

- data sent via SMS in NGTP format are encryped via the nowadays unsecure DES.

- the Combox does not protect against replay attacks.

BMW was notified in advance of the publication to provide fixes. The transport is now encrypted and BMWs server certificate is verified. The updates were delivered via ConnectedDrive config change. All BMW, Mini and Rolls Royce cars produced between March 2010 and 8 December 2014 are vulnerable. Cars without battery or parked in places without mobile connection still may be vulnerable, an update can be initiated manually.

See also

|

References

- Jump up^ “When was BMW founded?”. BMW Education. BMW. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved30 September 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g “Annual Report 2014” (PDF). BMW Group. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- Jump up^ “Best Global Brands – 2014 Rankings”. Interbrand.Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved26 March 2015.

- Jump up^ Frankfurt Stock Exchange

- Jump up^ “Fliegerschule St.Gallen – history” (in German). Archived from the original on 28 May 2007. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- Jump up^ Darwin Holmstrom, Brian J. Nelson (2002). BMW Motorcycles. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7603-1098-4. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- Jump up^ Johnson, Richard Alan (2005). Six men who built the modern auto industry. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing Company.ISBN 978-0-7603-1958-1.

- Jump up^ Oppat, Kay (2008). Disseminative Capabilities: A Case Study of Collaborative Product Development in the Automotive. Gabler Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8349-1254-1.

- Jump up^ Kiley, David (2004). Driven: inside BMW, the most admired car company in the world. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-26920-5.

- Jump up^ “BMW Model IIIA – Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum”. Nasm.si.edu. Archived from the original on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- Jump up^ Pavelec, Sterling Michael (2007). The Jet Race and the Second World War. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-99355-9.

- Jump up^ Radinger, Will; Schick., Walter (1996). Me262 (in German). Berlin: Avantic Verlag GmbH. p. 23. ISBN 978-3-925505-21-8.

- Jump up^ Kay, Anthony (2002). German Jet Engine and Gas Turbine Development 1930–1945. Airlife Publishing.ISBN 9781840372946.

- Jump up^ “BMW Strahljager Project I”. Nevingtonwarmuseum.weebly.com. 3 November 1944. Retrieved29 September 2013.

- Jump up^ Dan Johnson. “BMW Aircraft”. Luft46.com. Retrieved29 September 2013.

- Jump up^ Toronto Star 3 July 2004

- Jump up^ Becker, Clauspeter (1971), Logoz, Arthur, ed., “BMW 2500/2800”, Auto-Universum 1971 (in German) (Zürich, Switzerland: Verlag Internationale Automobil-Parade AG) XIV: 73

- Jump up^ Becker, p. 74

- Jump up^ Albrecht Rothacher (2004). Corporate Cultures And Global Brands. World Scientific. p. 239. ISBN 978-981-238-856-8.

- Jump up^ “Chris Bangle”. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- Jump up^ Smith, Jacquelyn (7 June 2012). “The World’s Most Reputable Companies”. Forbes.com. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “BMW Group”. BMW Group. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- Jump up^ Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung GmbH. “Seite 2 – Nachlass von Johanna Quandt: Die stille Erbschaft”. FAZ.NET.

- Jump up^ “World Motor Vehicle Production, OICA correspondents survey 2006” (PDF). Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- Jump up^ “Annual Report 2010” (PDF). BMW Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- Jump up^ Hilton Holloway (11 February 2011). “The future of BMW’s engines”. Autocar.

- Jump up^ “BMW to Pay $820 Million to China Car Dealers, Group Says”. Bloomberg News. 5 January 2015.

- Jump up^ Peter Gantriis, Henry Von Wartenberg. “The Art of BMW: 85 Years of Motorcycling Excellence”. MotorBooks International, September 2008, p. 10.

- Jump up^ “BMW 5-Series Gran Turismo”. reported by newBMWseries.com. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- Jump up^ Joe Lorio (May 2010). “Green: Rich Steinberg Interview: Electric Bimmer Man”. Automobile Magazine. Retrieved2013-02-13.

- Jump up^ “BMW introduces new i sub-brand, first two vehicles i3 and i8; premium mobility services and new venture capital company”.Green Car Congress. 2011-02-21. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- Jump up^ Sebastian Blanco (2013-09-18). “BMW i3 starts production in Germany using local wind power, US carbon fiber”. Autoblog Green. Retrieved 2013-09-19.

- Jump up^ Jay Cole (2013-11-15). “BMW Delivers First i3 Electric Vehicles In Germany Today”. InsideEVs.com. Retrieved 2013-11-16.

- Jump up^ Eric Loveday (2014-06-06). “World’s First BMW i8 Owners Take Delivery In Germany”. InsideEVs.com. Retrieved2014-06-07.

- Jump up^ Horatiu Boeriu (2015-07-10). “Worldwide sales of BMW i3 and i8 exceed 30,000 units in 2015”. BMWBlog. Retrieved2015-07-11. A total of 26,205 i3s and 4,456 i8s have been sold worldwide through June 2015.

- Jump up^ Jeff Cobb (2015-06-15). “Three More Plug-in Cars Cross 25,000 Sales Milestone”. HybridCars.com. Retrieved2015-07-11.

- Jump up^ “Race Results – Isle of Man TT Official Website”. iomtt.com.

- Jump up^ “Race Results – Isle of Man TT Official Website”. iomtt.com.

- Jump up^ “History of Dakar – RETROSPECTIVE 1979–2007” (PDF). Dakar. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2010. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- Jump up^ “BMW to quit F1 at end of season”. BBC News. 29 July 2009. Archived from the original on 29 July 2009. Retrieved29 July 2009.

- Jump up^ “BMW Diesel Wins 1998 24 Hours Nürburgring”.thedieseldriver.com.

- Jump up^ “BMW to return to DTM in 2012.”. bmwgroup.com.

- Jump up^ “German champions Borussia Dortmund join solar trend”.

- Jump up^ “BMW chosen to provide official Minis for 2012 London Olympics”. The Times. 18 November 2009. Retrieved 28 July2011.

- Jump up^ “BMW, USOC make 6-year sponsorship deal official”. CNN. 26 July 2010.[dead link]

- Jump up^ “BMW extends sponsorship of Wentworth PGA event”. Sportbusiness.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- Jump up^ “BMW Australia”. http://www.bmw.com.au. Retrieved 2015-08-27.

- Jump up^ “Performance Track Final Progress Report” (PDF). EPA. May 2009. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- Jump up^ Sauer, Paul. “Ultimate Factories”. Facts: BMW. National Geographic. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- Jump up^ “BMW Group once again sector leader in Dow Jones Sustainability Index”. bmwgroup.com.

- Jump up^ http://www.wbcsd.org/about/members/members-list-region.aspx

- Jump up^ BMW Group (16 May 2014). “BMW Group : Sustainable Value Report 2012 : Sustainability management”. bmwgroup.com.

- Jump up^ Bird, J and Walker, M: “BMW A Sustainable Future? “, page 11. Wild World 2005

- Jump up^ Christian Wüst (17 November 2006). “BMW’s Hydrogen 7: Not as Green as it Seems – SPIEGEL ONLINE”. Spiegel.de. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Jump up^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/6154212.stm BMW’s hydrogen car: Beauty or beast?

- Jump up^ “BMW Online Shop”. Shop.bmwgroup.com. 21 March 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- Jump up^ Interone Worldwide GmbH. “BMW Canada – The Ultimate Driving Experience”. Bmw.ca. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Jump up^ FAQ from the BMW Z4 Press Conference, as reported by BMWBLOG, 8 May 2009.http://www.bmwblog.com/2009/05/08/faq-from-the-recent-bmw-press-conference

- Jump up^ “Preview: 2011 BMW 335is Coupe – Posted Driving”. Network.nationalpost.com. Retrieved 28 August 2010.[dead link]

- Jump up^ Cunningham, Wayne (13 July 2010). “2011 BMW 335is (photos) – CNET Reviews”. Reviews.cnet.com. Archivedfrom the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- Jump up^ http://www.mrbimmer.com/bmw.information

- Jump up^ “First Drive: 2013 BMW 640i Gran Coupe – Automobile Magazine”. Automobilemag.com. Retrieved 29 September2013.

- Jump up^ “BMW Group takes top prize at the 2012 Corporate Entrepreneur Awards for premium car-sharing joint venture DriveNow. Jury impressed by willingness to trial new models of mobility”. Electricdrive.org. 30 October 2012. Retrieved29 September 2013.

- Jump up^ “BMW develops street lights with electric car-charging sockets”. Reuters.

- Jump up^ “BMW Films”. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- Jump up^ Stevens Sheldon, Edward (1891). “A short German grammar for high schools and colleges”. Heath. p. 1.

- Jump up^ Schmitt, Peter A (2004). Langenscheidt Fachwörterbuch Technik und Angewandte Wissenschaften: Englisch – Deutsch / Deutsch – Englisch (2nd ed.). Langenscheidt Fachverlag.ISBN 978-3-86117-233-8.

- Jump up^ “Bee em / BMW Motorcycle Club of Victoria Inc”. National Library of Australia. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- Jump up^ “No Toupees allowed”. Bangkok Post. October 2, 2009. Retrieved October 24, 2009.[dead link]

- Jump up^ Lighter, Jonathan E. (1994). Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang: A-G 1. Random House. pp. 126–7.ISBN 978-0-394-54427-4.

Beemer n. [BMW + ”er”] a BMW automobile. Also Beamer. 1982 S. Black Totally Awesome 83 BMW (“Beemer”). 1985 L.A. Times (13 April) V 4: Id much rather drive my Beemer than a truck. 1989 L. Roberts Full Cleveland39: Baby boomers… in… late-model Beemers. 1990 Hull High(NBC-TV): You should ee my dad’s new Beemer. 1991 Cathy(synd. cartoon strip) (21 April): Sheila… [ground] multi-grain snack chips crumbs into the back seat of my brand-new Beamer!1992 Time (18 May) 84: Its residents tend to drive pickups or subcompacts, not Beemers or Rolles.

- Jump up^ Lighter, Jonathan E. (1994). Random House Historical Dictionary of American Slang: A-G 1. Random House. p. 159.ISBN 978-0-394-54427-4.

Bimmer n. Beemer.

- Jump up^ “Bimmer vs. Beemer”. boston-bmwcca.org. Archived from the original on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 23 June 2007.

- Jump up^ Duglin Kennedy, Shirley (2005). The Savvy Guide to Motorcycles. Indy Tech Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7906-1316-1.

Beemer – BMW motorcycle; as opposed to Bimmer, which is a BMW automobile.

- Jump up^ Yates, Brock (12 March 1989). “You Say Porsch and I Say Porsch-eh”. The Washington Post. p. w45.

‘Bimmer’ is the slang for a BMW automobile, but ‘Beemer’ is right when referring to the company’s motorcycles.

[dead link] - Jump up^ Morsi, Pamela (2002). Doing Good. Mira. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-55166-884-0.

True aficionados know that the nickname Beemer actually refers to the BMW motorcycle. Bimmer is the correct nickname for the automobile

- Jump up^ Herchenroether, Dan; SellingAir, LLC (2004). Selling Air: A Tech Bubble Novel. SellingAir, LLC. ISBN 978-0-9754224-0-3.

- Jump up^ Hoffmann, Peter (1998). “Hydrogen & fuel cell letter”. Peter Hoffmann.

For the uninitiated, a Bimmer is a BMW car, and a Beemer is a motorcycle.

- Jump up^ English, Bob (7 April 2009). “Why wait for spring? Lease it now”. Globe and Mail (Toronto, CA: CTVglobemedia Publishing). Archived from the original on 28 July 2013.

If you’re a Bimmer enthusiast (not that horrible leftover 1980s yuppie abomination Beemer), you’ve undoubtedly read the reviews,

- Jump up^ THE NOSE: FWay students knew who they were voting for in school poll :[South Sound Edition]. 25 October 2002. The News Tribune,p. B01. Retrieved 6 July 2009, from ProQuest Newsstand. (Document ID: 223030831) |quote=We’re told by auto snobs that the word ‘beemer’ actually refers to the BMW motorcycle, and that when referring to a BMW automobile, the word’s pronounced ‘bimmer.’

- Jump up^ 25-Wed-2005/news/26427972.html “ROAD WARRIOR Q&A: Freeway Frustration” Check

|url=scheme (help). Las Vegas Review-Journal. 25 May 2005.I was informed a while back that BMW cars are ‘Bimmers’ and BMW motorcycles are ‘Beemers’ or ‘Beamers.’ I know that I am not here to change the world’s BMW jargon nor do I even own a BMW, but I thought I would pass along this bit of info as not to offend the car enthusiast that enlightened me.

- Jump up^ “GWINNETT VENT.(Gwinnett News)”. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution (Atlanta, GA). 11 February 2006. p. J2.

It is Bimmers people, Bimmers. Not Beamers, not Beemers. Just Bimmers. And start pronouncing it correctly also.

No, it’s BMWs, not Bimmers.

WOW! Some Beamer driver must be having a bad hair day. - Jump up^ Zesiger, Sue (26 June 2000). “Why Is BMW Driving Itself Crazy? The Rover deal was a dog, but it didn’t cure BMW’s desire to be a big-league carmaker—even if that means more risky tactics”. Fortune Magazine (CNN).

Bimmers (yes, it’s ‘Bimmer’ for cars—the often misused ‘Beemer’ refers only to the motorcycles).

- Jump up^ “International – Readers Report. Not All BMW Owners Are Smitten”. Business Week (The McGraw-Hill Companies). 30 June 2003.

Editor’s note: Both nicknames are widely used, though Bimmer is the correct term for BMW cars, Beemer for BMW motorcycles. A Google search yields approximately 10 times as many references to Bimmer as to Beemer.

- Jump up^ “BMW Commissions Artists for Auto Werke Art Project”. Art Business News 27 (13). 2000. p. 22.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Patton, Phil (12 March 2009). “These Canvases Need Oil and a Good Driver”. The New York Times. p. AU1.

- Jump up^ Friedel, Helmut; Storr, Robert (2007). Gerhard Richter: Red – Yellow – Blue. Prestel. ISBN 978-3-7913-3860-6.

- Jump up^ Shea, Christopher (27 March 2009), “Action Painting, motorized”, The Boston Globe

- Jump up^ “”Economist, The (US) (21 April 2001). “When merchants enter the temple; Marketing museums”. The Economist Newspaper and The Economist Group.

- Jump up^ Vogel, Carol (3 August 1998). “Latest Biker Hangout? Guggenheim Ramp”. The New York Times. p. A1.

- Jump up^ “BMW arts series aims at black consumers”. Automotive News80 (6215). 7 August 2006. p. 37.

- Jump up^ “BMW Group assembles first car in Brazil”. press.bmwgroup.com. 9 October 2014. Retrieved 21 December2014.

- Jump up^ “Reasons for Selection, 2009 Greater Toronto’s Top Employers Competition”. Eluta.ca. 24 September 2013. Retrieved29 September 2013.

- Jump up^ General Overview Brilliance Auto Official Site

- Jump up^ “BMW opens China factory – TestDriven.co.uk”. Testdriven.co.uk. 21 May 2004. Archived from the original on 21 March 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- Jump up^ Brands and Products > BMW Sedan Brilliance Auto Official Site

- Jump up^ Interone Worldwide GmbH (11 December 2006). “International BMW website”. Bmw.in. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- Jump up^ “Joining rivals, BMW to set up $1bn plant in Mexico”. Mexico Star. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- Jump up^ “Corporate Information: History”. BMW South Africa.

- Jump up^ “BMW South Africa – Plant Rosslyn”. Bmwplant.co.za. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- Jump up^ “Out with the old, in with the new” (Press release). BMW AG. 16 October 2006. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- Jump up^ Bennett, Jeff (14 October 2010). “BMW to Expand Plant in South Carolina”. The Wall Street Journal. p. B5.

- Jump up^ “BMW Plant Spartanburg leads U.S. auto exports”. Roundel(BMW Car Club of America): 30. April 2015. ISSN 0889-3225.

- Jump up^ “BMW Still the Ultimate Driving Machine”. Forbes.com. 31 May 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Jump up^ Sofia Johansson (22 March 2013). “BMW Updates Their Iconic Sound Logo”. PSFK. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Jump up^ “BMW Introduces New Sound Logo”. Autoevolution.com. 19 March 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Jump up^ “New sound logo for BMW revealed”. Motortorque.com. 19 March 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Jump up^ BMW. “The origin of the BMW logo”. Retrieved 29 December2011.

- Jump up^ Stephen Williams (7 January 2010). “BMW Roundel: Not Born From Planes”. The New York Times. Retrieved 29 December2011.

- Jump up^ Titcomb, James (6 July 2012). “Alarming moment thieves silently steal BMW by programming a blank key that cost just £70 in new crime trend sweeping Britain”. London: Daily Mail. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- Jump up^ “Pistonheads report into thefts via obd”. Retrieved 2 July2012.

- Jump up^ Torchinsky, Jason (6 July 2012). “Watch Hackers Steal A BMW In Three Minutes”. Jalopnik. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- Jump up^ Van den Brink, Rob. “Dude, Your Car is Pwnd” (PDF). SANS Institute.

- Jump up^ Auto, öffne dich! Sicherheitslücken bei BMWs ConnectedDrive, c’t, 2015-02-05.

The info is mostly coming from wikipedia BMW english

The all-new BMW i8. Official Launch Video.

The Epic Driftmob feat. BMW M235i

The first-ever BMW M2. Official launchfilm.

Classic BMW Commercial

BMW Commercial 002 “Ambush”

For lots more BMW ads go tu YOU TUBE