| Monica 560 | |

|---|---|

|

1973 Monica 560

|

|

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | Monica |

| Model years | 1973 – 1975 |

| Assembly | France: Balbigny, Loire |

| Designer | Tony Rascanu, David Coward |

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Grand tourer |

| Body style | 4-door sedan |

| Layout | Longitudinal front-engine, rear-wheel drive |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | 5.6 L Chrysler LA V8(gasoline) |

| Transmission | 3-speed automatic (TorqueFlite ) 5-speed manual (ZF) |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 2,769 mm (109.0 in) |

| Length | 4,928 mm (194.0 in) |

| Width | 1,803 mm (71.0 in) |

| Height | 1,346 mm (53.0 in) |

| Kerb weight | 1,821 kg (4,015 lb) |

Monica is the name of a French luxury automobile produced in the commune of Balbigny in the department of Loire between 1972 and 1974.

The beginning

The Monica car was a project of Jean Tastevin, a graduate engineer of the École centrale de Paris. His father Arnaud bought the Atelier et Chantiers de Balbigny in 1930. That company was a manufacturer of mining and railway equipment. In 1955 Jean succeeded his father, becoming Chairman and Managing Director. He renamed the company Compagnie française de produits métallurgiques, or CFPM, and began to specialize in the manufacture and rental of railroad tank cars. The factory where the rolling stock was manufactured operated under a different name, being Compagnie Française de Matériels Ferroviaires (CFMF). The company prospered, eventually coming to have 400 employees.

Tastevin was an automobile enthusiast who personally owned cars from Aston Martin and Facel Vega. After Facel Vega shut down in 1964 he bought a Jaguar, but regretted not being able to buy a French-made car of that class.

In pursuit of both his interest in cars and a way to diversify his railway business, Tastevin began making plans to launch his own brand of automobile in 1966. He made his long-time assistant, Henri Szykowksi, the project manager. He would also set aside a portion of his factory in Balgigny so that the cars could truly be said to be made in France.

The car was named in honour of Tastevin’s wife, Monique Tastevin.

Development history and prototypes

Automotive engineer and racing driver Chris Lawrence’s company LawrenceTune Engines had developed a 2.6-litre version of the Standard engine used in the Triumph TR4. Lawrence’s version used a crossflow cylinder head of his own design and Tecalemit-Jackson fuel injection to make a claimed 182 bhp (136 kW) bhp. Automotive journalist Gérard ”Jabby” Crombac had seen the engine at the 1966 Racing Show at Olympia West Hall in London. The article he wrote about it had caught Tastevin’s eye. Tastevin wrote to Lawrence asking about having LawrenceTune supply 250 engines per year for his new car. Upon learning that the car was not yet developed, Lawrence offered the services of his own company. Crombac, who was familiar with Lawrence’s racing exploits, vouched for Lawrence and Tastevin entrusted development of the Monica to LawrenceTune.

The first chassis and the jig to produce it were built together. Lawrence laid out a chassis with a central tunnel made of four square-section 18 gauge steel tubes with extensive cross-bracing. Two long steel boxes with triangular cross-sections were made of 16 gauge steel and attached to the chassis in the door sill area. These stiffened the chassis and were also to serve as the car’s fuel tanks. 16 gauge aluminum formed the front and rear bulkheads and floors and was used on both sides of the central tunnel to stiffen the car further. Voids in the tunnel were filled with expanded polyurethane foam to add even more stiffness and deaden sound.

The front suspension used very tall uprights with the wheel spindles on one side and a short stub axle extending inwards on the other. Springing was by vertically mounted coil-over-damper units mounted inboard and operated through rocker-style upper arms. The lower arms were conventional wide-based wishbones made of a one-piece wishbone and long radius arm running back towards the bulkhead. Steering was rack-and-pinion mounted high, at the same level as the upper wishbone.

The rear suspension was a De Dion system with coil springs, two parallel leading links on each side and a Panhard rod. The differential was from the Rover P6B (also known as the Rover 3500) with a crown-and-pinion made by Hewland, but with an additional nose-piece that gave the option of two rear-axle ratios; a high-numeric ratio for in town and a low-numeric ratio for high-speed cruising. A lever in the cockpit allowed the ratio to be changed while in motion.

Braking was provided by a dual-circuit power assisted Lockheed and Girling system with 12-inch vented disks in front and 10-inch solid disk brakes in the rear. The rear brakes were mounted inboard and the front brakes were mounted to the stub-axle on the front upright, which brought them out of the wheels and into the air-stream for cooling.

As the prototype chassis was nearing completion Lawrence began to have second thoughts about using the LawrenceTune/Standard-Triumph engine. Lawrence knew that the Triumph engine was to be phased out of production by 1967. He also felt that this relatively heavy, rough, and noisy engine was not appropriate for a new luxury car.

Lawrence put Tastevin in touch with Edward C. “Ted” Martin, who had designed an engine that Lawrence thought would work well in the Monica. After evaluating the engine Tastevin bought the design, rights and existing tooling for Ted Martin’s engine. The agreement included four complete 3.0 litre engines.

The Martin engine was an all-alloy V8 with a single overhead camshaft (SOHC) per bank driven by a toothed-belt (originally Gilmer belt – see also Timing belt). Designed for the new 3-litre limit announced for the 1966 Formula One season, it weighed just 230 lb (100 kg) with ancillaries and produced 270 bhp (200 kW)@7000 rpm. An unusual feature of the Martin V8 was that four of the connecting rods were forked at the big end, much like those on the Rolls Royce Merlin engine. The connecting rod for the opposing cylinder bore fit into the gap of the forked rod. This meant that the cylinder banks were not offset on the crank-line, reducing overall engine length. The engine was used in the Pearce-Martin F1 car as well as the Lucas-Martin, a modified Lotus 35 Formula 2 frame that was run briefly in Formula One. It also appeared in 2.8-litre form in some specials, including some of Lawrence’s own Deep Sanderson sports and racing cars.

This initial prototype first ran at Silverstone in 1968 without bodywork. The drivetrain for the car was a 3-litre Martin V8 driving through a Triumph TR4 gearbox with overdrive. The car weighed 1070 kg. Overall performance was good but the testing uncovered problems with the engine and its lack of road-car ancillaries.

Bodywork for the first prototype was fabricated by Maurice Gomm. This car was very different in appearance from the subsequent prototypes and the production models and has been compared to an oversized Panhard CD. Neither Tastevin nor his wife were happy with the appearance of the first prototype.

A second prototype chassis was built and sent to Williams & Pritchard, who produced a body for it in aluminum. The style of this body was much more angular than the first. Tastevin personally requested some last-minute changes to the shape which would be undone in later prototypes, but in general prototype #2 set the general direction for subsequent bodies. This second car was registered as a Deep Sanderson and given registration number 2 ARX. After its use as a development mule prototype #2 was used as a personal car by team member Colin James, after which it was acquired by Peter Dodds, another member of the Monica team.

In 1969 prototype chassis #3, the first to receive a ZF 5-speed manual transmission, was built. At this time the Tastevins introduced Tudor (Tony) Rascanu, a Romanian exile and former shop manager for Vignale in Italy, to the project. Rascanu was entrusted with the job of completely restyling the bodywork for the third prototype, but was not allowed to make any modifications to Lawrence’s chassis, which was to be sent to French coach-builder Henri Chapron in Paris. Chapron was to build a full-sized maquette, or body-form, of the revised car under Rascanu’s oversight. Rascanu and Capron’s work met with Tastevin’s approval. With hidden headlamps in a sloping aerodynamic nose and wide horizontal taillights it was much more appealing than the previous two attempts. The maquette was then sent to Carrozzeria Alfredo Vignale in Turin to be used as a base for Vignale to produce a body in steel.

Before delivering the maquette to Vignale, Tastevin asked Lawrence to first deliver prototype #2 to the workshops of Virgilio Conrero, also in Turin. The famous Alfa mechanic was to do a detailed assessment of the Martin engine and evaluation of the car’s performance. Conrero was critical of almost every aspect of the Martin engine and was skeptical of the power curves provided by Lawrence. He told the factory “this engine is a trap that will never work under normal traffic conditions”. Conrero insisted on a flying-kilometre test of the prototype, after which he would run his 2-litre Giulietta on the same course for comparison. Lawrence suspected that Conrero was trying to discredit both the Martin engine and LawrenceTune in an attempt to take Lawrence’s place on the Monica project. He examined the times recorded for the Monica’s run and discovered an irregularity in the numbers. When Tastevin confronted Conrero with this information the testing was halted and Conrero’s involvement in the project ended.

Lawrence delivered chassis #3 to Vignale’s carrozeria, and they completed the body in steel. While prototype #3 was a significant improvement the Tastevins were not yet entirely satisfied with its appearance. Performance of this car was also disappointing due to it being between 200 kg (440 lb) and 250 kg (550 lb) overweight. By way of explanation Lawrence drilled a hole into the scuttle. The drill penetrated 13 mm (0.5 in) of lead. Vignale, in the mean time, sold his company to DeTomaso in December 1969 and died three days later in an automobile accident while driving a Maserati.

During the May 1968 events in France, Tastevin decamped the entire staff of CFPM to Geneva and tasked Lawrence to keep the Monica project going. Tastevin provided Lawrence with funding to find sub-contractors to build cars in England. Lawrence approached Jensen, who he knew were already building cars for Sunbeam, Volvo and Austin-Healey as well as their own C-V8s and Interceptors. Jensen was not set up to produce the body panels though. Panels for their other assembly contracts came from outside of the company. Lawrence took prototype #3 and went looking for someone to provide the panels. He found a company named Airflow Streamline in Luton that specialized in producing aluminum cabs for trucks. Airflow only asked for a complete set of engineering drawings, a chassis and the number of body panels that Lawrence would require. Chassis #4 and #6 were delivered to Airflow Streamline and Rascanu was installed there to supervise the production of the necessary drawings.

Another sub-contractor would be needed to supply the engines. Two possibilities presented themselves. One was Coventry-Victor, and the other was Rolls-Royce. Lawrence had heard that Rolls-Royce had recently idled one of their production facilities due to the loss of a contract and might be interested in taking on the Martin V8 project. Lawrence met with representatives from Rolls-Royce, who were fascinated by the small size of the Martin V8 and intrigued by the forked connecting rods so reminiscent of those in Rolls-Royce’s own Merlin. Rolls-Royce subsequently won another defense contract which would reactivate the previously idled plant and bowed out of negotiations. Lawrence went back to Coventry-Victor.

In the intervening time things had settled down in Paris, and Tastevin wanted to move the project along quickly. Chassis #5 was sent to the factory in Balbigny while Lawrence set about establishing a machine shop at LawrenceTune Engines able to produce the engines as well. Problems with castings coming from a company called Birmingham Alloys prompted Lawrence to have Tastevin search his contacts in the French aluminum industry for an alternative supplier, settling on a company called Montupet.

Airflow Steamline was still without their technical drawings and was not getting any information out of Paris. It turned out that Rascenu, sadly, had died in 1970 before being able to complete the drawings. Lawrence met with Airflow Streamline to discuss the changes they wanted in the maquette and Lawrence convinced Airflow to build two bodies on the two chassis they had using prototype #3, which would be left there, as a structural guide. The car they would produce, prototype #4, would be Lawrence’s favourite Monica of all.

David Coward was hired from Autocar magazine where he was working as an illustrator. Prior to that he had worked at coachbuilder James Young. Coward refined Rascanu’s design by lowering the side window line and deepening the windscreen to give the car a more contemporary appearance. The body was also lowered three inches between the floor pan and the roof and four inches were added to the width.

After sorting out some issues with prototype #4 attention turned to tooling. Tooling to produce the bodywork in aluminum turned out to be prohibitively expensive, but a company named Abbate was found in Turin that would make tooling out of resin that would be able to produce up to 100 body sets in steel. The price for the set would be £100,000.

When the unrest in Paris had subsided the idea of contracting out production of the car had ended, but Tastevin had kept Coventry-Victor under contract to produce the engines. They had been asked to produce 25 copies of the engine in a 2.8 litre displacement. Coventry-Victor was only able to produce 18 engines before declaring bankruptcy.

At the same time Lawrence had pressed ahead with producing the engines at LawrenceTune headquarters in England. Tests of the 2.8 litre engine led him to believe that this version was under-powered for the car, and so he enlarged his. With displacement increased to 3423 cc fed by four 2-barrel Weber 40 DCLN down-draught carburetors and the Monica name in script cast into its valve-covers, the revised engine produced 240 bhp (180 kW)@6000 rpm. While maximum torque wasn’t produced until 4000 rpm the torque curve was relatively flat from 2500 to 4000 rpm.

Eventually the technical drawings were completed and approved by Tastevin, which Lawrence delivered to Turin along with prototype #4 so that production of the body panels using the resin/steel hybrid tooling could begin. Comparisons have been drawn between the final shape of the Monica and many of its contemporaries, with the front view having been compared to the Maserati Indy and Lotus Elan +2, the rear to the Ferrari 365 GT 2+2, and the side elevation to the Aston Martin DBS.

Problems continued with the engine however. Blown head-gaskets were common and difficulties with deliveries of both block and cylinder head castings held back development.

In an exclusive article in l’Auto-Journal, writers Jean Mistral and Gilles Guérithaut published a preview of the Monica’s debut at the upcoming Salon de l’Auto in October along with an interview with Tastevin. Among the things the founder revealed were his plans to build 400 cars per year.

Tastevin decided that the car would debut at the Salon de l’Auto show in Paris in October 1971. The car on display was powered by a Martin V8 and was called the Monica 350. Tastevin arranged to have a car raised to the tenth floor of a Paris hotel the day before the show, and then have it moved over to the Salon, where the car was received enthusiastically. The morning after the day of the show Lawrence was approached by Zora-Arkus Duntov, who asked if he could take the car for a drive. Lawrence handed him the keys.

Shortly after the Paris auto show, Tastevin phoned Lawrence and told him that he had arranged for the car to be evaluated by a team from Matra. A team of six from Matra drove the cars for over three hours straight and then met with Tastevin. The outcome of the evaluation was that the Matra engineers thought that the car should go into production, but only with a different engine.

Consideration was given to using an Aston Martin V8, but that option was too expensive to pursue. Lawrence was sent to the United States to meet with Ford, Chevrolet and Chrysler to arrange for a supply of engines. Ford and Chevrolet were quickly eliminated from the running but Chrysler was very open to the idea. At the beginning of 1973 the decision was finally made to abandon the Martin V8 and adopt a North American engine, specifically the 5.6-litre (5563 cc) “340” Chrysler LA series V8.

To handle the extra weight power-steering was added, and the rear axle was beefed up. As an added bonus, Chrysler shipped the engines with an air-conditioning compressor, so that feature was added at the same time. Other minor changes included fabricating the requisite motor mounts, having two new vents let into the fenders and, on later models, two additional grilles fitted to the hood.

During road testing the new Chrysler engines began to fail. After investigating it became apparent that the cause of these problems was that these engines were not designed to run for extended duration at the speeds possible on the continent. Lawrence returned to the States looking for the resources to remedy these problems.

The engines destined for use in Monicas would all be specially tuned by Racer Brown in the United States. Modifications to the engines included a Racer Brown stage 3 road camshaft with hydraulic lifters, an Edelbrock Torquer intake manifold, a 4-barrel Holly R6909 750 CFM carburetor, a Chrysler marine specification oil pump, Clevite shell bearings, Forge True pistons, Marine specification valves, and a Felpro race-quality gasket set.[1]:181 The compression ratio was 10.5:1. All of these changes combined to bring output to 285 bhp (213 kW)@5400 rpm and 333 lb⋅ft (451 N⋅m)@4000 rpm.

It is reported that some cars may have been built with the larger 5.9 litre (5898 cc) “360” version of the Chrysler LA engine. These cars would have been designated Monica 590s. The dimensions attributed to this version by various sources differ, sometimes significantly, from those of the 560 model. In particular the 590 is listed as being 630mm shorter with a 100mm shorter wheelbase and 140 kg heavier. It was also more powerful, the engine being rated at 315 bhp (235 kW) and 332 lb⋅ft (450 N⋅m).

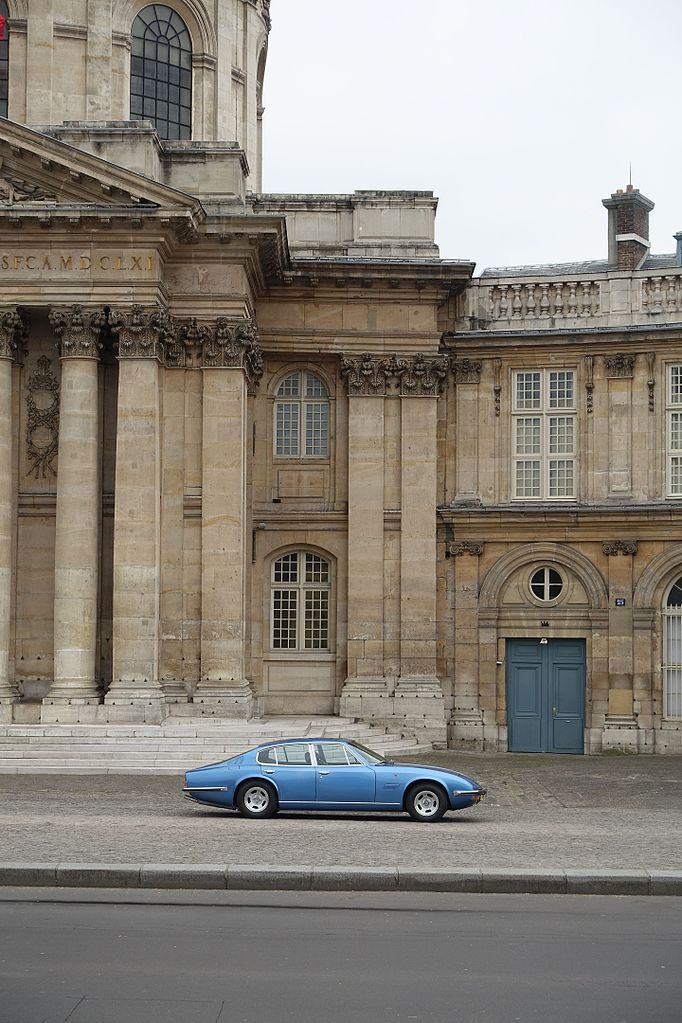

The revised and renamed Monica 560 made its world premier at the Geneva Auto Show in March 1973. It would appear again at the Paris Auto Show in October. The car was priced at 164,000 francs (roughly US$34,000 at the time), at a time when a Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow cost 165,000 francs.

After the Geneva show Tastevin invited several racing drivers and automotive journalists to Paul Ricard’s circuit, Le Castellet, to evaluate the new Chrysler-powered car. Among those there was driver/journalist Paul Frère, whom Tastevin invited to “lend a hand” in sorting out the car’s handling. He would also be the person who wrote the semi-official obituary for the Monica car.

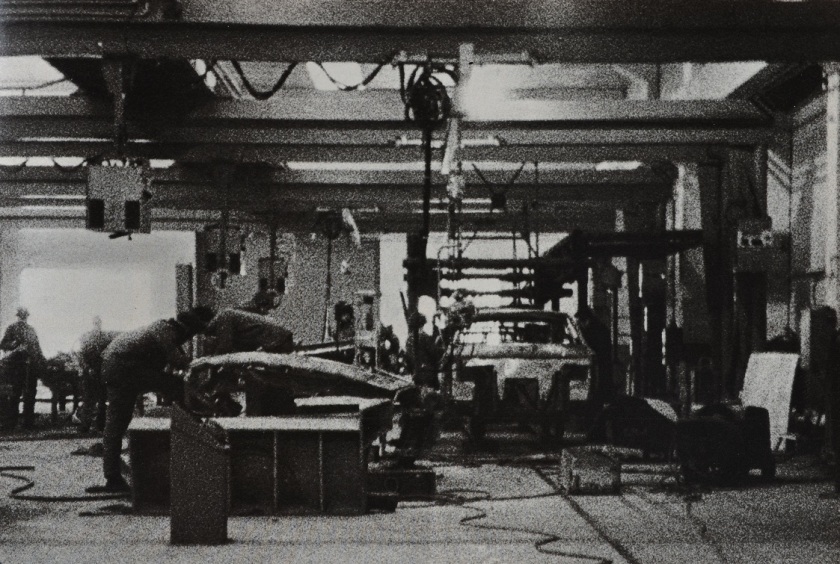

A rapid succession of prototypes would be built to finalize the car. The cars at Le Castellet were numbers 8 and 9. Numbers 10 and 11 were built for crash-testing and numbers 12, 13 and 14 came after. Prototype 14 was basically pre-production and would eventually be one of the cars Tastevin kept for his personal use. Tastevin had hired a director to get production under way at Balbigny, but nothing was built for a year while the new director stalled and made changes to the car. Eventually Tastevin fired the directory and turned production over to LawrenceTune again while he looked for a new director. The car was also subsequently shown at the Earls Court auto show.

Views:

The car

With the long development period finally at an end, production gets underway in Balbigny.

The car is built on Lawrence’s steel-tube and sheet metal chassis. The body is Rascanu’s design with Coward’s revisions executed entirely in steel. Five exterior colours are available: Atlantic Blue, Azure Blue, Purple Amaranth, Chestnut Brown and Beige Sand. The final version of Lawrence’s rocker-arm/De Dion suspension is automatically leveling, and the car sits on four Michelin 215/70VR-12 Collection tires mounted on 14 inch alloy wheels. The original sill-mounted fuel tanks have been replaced with a single tank under the floor of the trunk due to regulatory restrictions.

The power-assisted rack-and-pinion steering is connected to an adjustable steering column that is topped by a custom Motolita steering wheel.

Braking on the production Monica was still a dual circuit system with Lockheed disks inboard at the front operated by a 4-piston caliper and Girling disks at the rear operated by a 3-piston caliper but the disks front and rear were both now 11 inch ventilated pieces.

The seats are upholstered in Connolly leather available in three colours: Marine, Havana, and Champagne. The floor is covered in Shetland wool carpeting. The dashboard is finished in burl elm wood and suede.

The state of the car is monitored by a brace of custom Jaeger instruments all bearing the Monica name. Gauges include a speedometer, tachometer, oil temperature gauge, oil pressure gauge, ammeter, water temperature gauge, fuel gauge, and clock.

The windows are electrically operated. A High-fidelity sound system with integrated tape recorder and player is standard equipment, as is an air-conditioning system with separate controls for the rear seat passengers. The doors on the Monica are electrically operated to open and close silently at the touch of a button. In the trunk is a complete set of custom luggage.

With a quoted top speed of 240 km/h (150 mph) the Monica 560 could lay claim to being “The fastest sedan in the world” at the time.

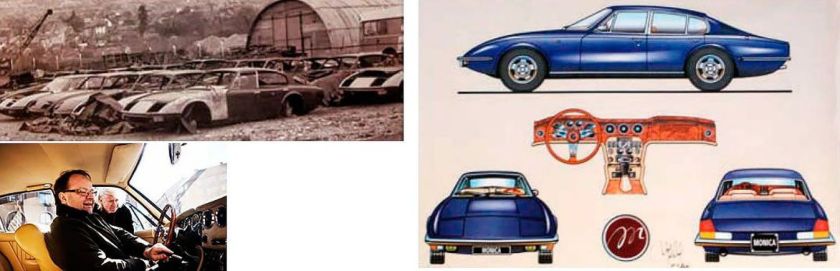

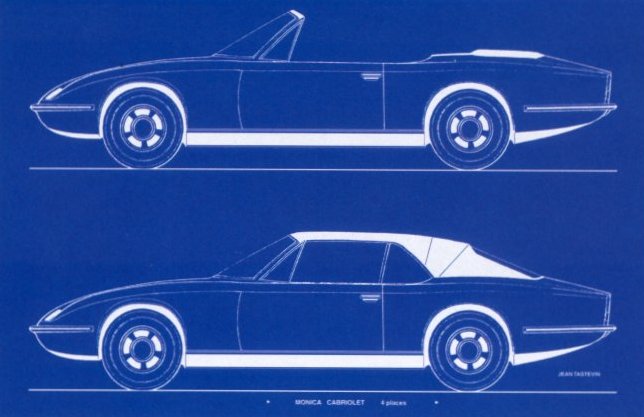

Photos from the period indicate that a future coupe and convertible were already being planned.

The end

The Monica 560 makes its last public appearance at the Paris Auto Salon Paris Auto Show in October 1974. On February 7 of 1975 Tastevin announces the cessation of production and closes the company.

Many factors contributed to the failure of the car. It endured a seven-year long gestation period. The car was remarkably expensive while lacking the kind of reputation or recognition enjoyed by other more established marques in this market. It faced competition from many similar-sized low-volume manufacturers. Finally, it had the misfortune to be officially released just as the first major oil crisis made fuel prices jump and large expensive motorcars less desirable.

Five Monicas remaining at the LawrenceTune headquarters were sold by Lawrence to Cliff Davis and Bernie Ecclestone, the proceeds being payment for LawrenceTunes work for Tastevin. Lawrence was driving pre-production car #21 at the time. The Tastevins kept three Monicas for their own use.

The production assets of the Monica company and as many as thirty cars in various stages of completion were sold to French race driver and Formula One team owner Guy Ligier. Ligier did not resume production.

In April 1976 Motor Sport magazine reported an announcement by Bob Jankel of Panther Westwinds that his company and C.J. Lawrence and Co. would resume production of the Monica. C.J. Lawrence and Co. would manufacture sub-assemblies and Panther would assemble, paint and trim the car. Power was elsewhere rumored to be coming from a Jaguar V12 motor. Production would move from Balbigny to Surrey. Nothing came of these plans.

Six production Monicas are known to exist. At least three of the prototypes are reported to remain in Britain. Chris Lawrence personally owned a production Monica for several years that was sold from his estate.

Gallery

-

Front three-quarter view

Rear three-quarter view

Rear view

Interior

Trunk logo

Doorsill logo

collected pictures

Literature

- Monica – edited by Emory Christer ISBN 978-6-134977-82-1

- Preston Tucker & Others: Tales of Brilliant Automotive Innovations ISBN 978-1-845840-17-4

- Monica, automobile française de prestige by Frédéric Brandely. Hardcover (published June, 2012) ISBN 979-1090084049

- Monica, automobile française de prestige by Frédéric Brandely. Paperback. ISBN 978-2-913307-13-1

- Kevin Brazendale: The Encyclopedia of classic cars. Advanced Marketing Services, London 1999, ISBN 1-57145-182-X (engl.).

References

- ^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabacadaeafagahaiajakal Lawrence, Chris (2008). Morgan Maverick. Yorkshire: Douglas Loveridge Publications. ISBN978-1-900113-04-5.

- ^ abc “1972/1975 Monica…”http://www.gatsbyonline.com. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- ^ “London Racing Car Show 1967”. http://www.sportscars.tv. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ^ “Ted Martin and the AMCO Engines”. http://www.modelenginenews.org. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ^ “Anglo-French Monica”. http://www.motorsportmagazine.com. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ^ “Monica Prototype No. 2”. classiccars.brightwells.com. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ^ “Tudor Rascanu, de Dody à Tony”. voronet.centerblog.net. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ^ “ECLIPSE AVORTEE”. http://www.automobile-sportive.com. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ^ “Monica : Belle, luxueuse, française et ancêtre des coupés 4 portes”. blog.p.free.fr. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ^ Georgano, Nick (2001). The Beaulieu Encyclopedia of the Automobile (2nd ed.).

- ^ “1973 Monica 590 technical specifications”. http://www.carfolio.com. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ^ “History of Lawrence Tune …… continued”. http://www.lawrence-tune.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ^ “Monica”. http://www.allcarindex.com. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ^ “1974 Monica”. http://www.silverstoneauctions.com. Retrieved 2016-12-13.