Rolls-Royce

and

Bentley Motors

The Rolls-Royce logo

|

|

| Private | |

| Industry | Automotive |

| Fate | Sold to Volkswagen Group |

| Successor | Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited |

| Founded | 1973 |

| Defunct | 1998 |

| Headquarters | United Kingdom |

| Products | Automobiles |

| 120 million (2008 est.) | |

| Owner | Vickers plc |

Rolls-Royce Motors was a British car manufacturer, created in 1973 during the de-merger of the Rolls-Royce automotive business from the nationalisedRolls-Royce Limited. Vickers acquired the company in 1980 and sold it to Volkswagen in 1998.

History

The original Rolls-Royce Limited had been nationalised in 1971 due to the financial collapse of the company, caused in part by the development of the RB211 jet engine. In 1973, the British government sold the Rolls-Royce car business to allow nationalised parent Rolls-Royce (1971) Limited to concentrate on jet engine manufacture.

In 1980, Rolls-Royce Motors was acquired by Vickers.

Sale to Volkswagen

In 1998, Vickers plc decided to sell Rolls-Royce Motors. The leading contender seemed to be BMW, who already supplied internal combustion engines and other components for Rolls-Royce and Bentley cars. Their final offer of £340m was outbid by Volkswagen Group, who offered £430m.

As part of the deal, Volkswagen Group acquired the historic Crewe factory, plus the rights to the “Spirit of Ecstasy” mascot and the shape of the radiator grille. However, the Rolls-Royce brand name and logo were controlled by aero-engine maker Rolls-Royce plc, and not Rolls-Royce Motors. The aero-engine maker decided to license the Rolls-Royce name and logo to BMW and not to Volkswagen, largely because the aero-engine maker had recently shared joint business ventures with BMW. BMW paid £40m to license the Rolls-Royce name and “RR” logo, a deal that many commentators thought was a bargain for possibly the most valuable property in the deal. Volkswagen Group had the rights to the mascot and grille but lacked rights to the Rolls-Royce name in order to build the cars, likewise BMW had the name but lacked rights to the grille and mascot.

The situation was tilted in BMW’s favour, as they could withdraw their engine supply with just 12 months notice, which was insufficient time for VW to re-engineer the Rolls-Royce cars to use VW’s own engines. Volkswagen claimed that it only really wanted Bentley anyway as it was the higher volume brand, with Bentley models out-selling the equivalent Rolls Royce by around two to one.

Loss of Rolls-Royce marque

After negotiations, BMW and Volkswagen Group arrived at a solution. From 1998 to 2002, BMW would continue to supply engines for the cars and would allow Volkswagen use of the Rolls-Royce name and logo. On 1 January 2003, only BMW would be able to name cars “Rolls-Royce”, and Volkswagen Group’s former Rolls-Royce/Bentley division would build only cars called “Bentley”. The last Rolls-Royce from the Crewe factory, the Corniche, ceased production in 2002, at which time the Crewe factory became Bentley Motors Limited, and Rolls-Royce production was relocated to a new entity in Goodwood, England known as Rolls-Royce Motor Cars.

Despite losing control of the Rolls-Royce marque to BMW, however, the former Rolls-Royce/Bentley subsidiary retains historical Rolls-Royce car assets such as the Crewe factory and

Cars

1965–80 Silver Shadow—the first Rolls-Royce with a monocoque chassis; started with a 6.23 L V8 engine, later expanded to 6.75 L; shared its design with the

1970 Bentley T series 1 with chrome bumpers

1970 Bentley T series 1 with chrome bumpers

1992 Rolls-Royce Phantom VI Landaulette

1992 Rolls-Royce Phantom VI Landaulette

1968–91 Phantom VI

Second-generation Rolls-Royce Corniche

Second-generation Rolls-Royce Corniche

1971–96 Corniche I-IV

1975–86 Camargue styled by Paolo Martin with a Pininfarina body

1980–98 Silver Spirit/Silver Spur—design shared with the Bentley Mulsanne

Bentley models were produced mostly in parallel with the above cars. The Bentley Continental coupés (produced in various forms from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s) did not have Rolls-Royce equivalents. Very expensive Rolls-Royce Phantom limousines were also produced.

Volkswagen Group era

1999 Rolls-Royce Silver Seraph

1999 Rolls-Royce Silver Seraph

1998–2002 Silver Seraph—This shared its design with the

Bentley Arnage, which sold in much greater numbers.

2000–02 Corniche V—This two-door convertible shared its design with the

Bentley Azure and was the most expensive Rolls-Royce until the introduction of the 2003 Phantom.

Bentley

|

|

| Subsidiary | |

| Industry |

|

| Fate |

|

| Founded | 18 January 1919 |

| Founder |

|

| Headquarters | Crewe, England, United Kingdom |

|

Area served

|

Worldwide |

|

Key people

|

Wolfgang Dürheimer Chairman, CEO John Paul Gregory (Head of Exterior Design) Darren Day (Head of Interior Design) |

| Products |

|

|

Production output

|

|

| Services | Automobile customisation |

| Revenue |

|

| Profit |

|

|

Number of employees

|

3,600 (2013) |

| Parent | Volkswagen Group |

| Website | bentleymotors.com |

| Footnotes / references |

|

Bentley Motors Limited (/ˈbɛntli/) is a British manufacturer and marketer of luxury cars and SUVs—and a subsidiary of Volkswagen AG since 1998.

Headquartered in Crewe, England, the company was founded as Bentley Motors Limited by W. O. Bentley in 1919 in Cricklewood, North London—and became widely known for winning the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1924, 1927, 1928, 1929, 1930, and 2003.

Prominent models extend from the

historic sports-racing Bentley 4½ Litre and

1930 Bentley Speed Six; the more recent

1953 Bentley R Type Continental,

Bentley Turbo R, and

Bentley Arnage; to its current model line—including the

2012 Bentley Continental Flying Spur Speed

2012 Bentley Continental Flying Spur Speed

2012 Bentley Continental GT (II)

2012 Bentley Continental GT (II)

2016 Bentley Bentayga and the

Mulsanne—which are marketed worldwide, with China as its largest market as of November 2012.

Today most Bentleys are assembled at the company’s Crewe factory, with a small number assembled at Volkswagen’s Dresden factory, Germany, and with bodies for the Continental manufactured in Zwickau and for the Bentayga manufactured at the Volkswagen Bratislava Plant.

The joining and eventual separation of Bentley and Rolls-Royce followed a series of mergers and acquisitions, beginning with the 1931 purchase by Rolls-Royce of Bentley, then in receivership. In 1971, Rolls-Royce itself was forced into receivership and the UK government nationalised the company—splitting into two companies the aerospace division (Rolls-Royce Plc) and automotive (Rolls-Royce Motors Limited) divisions—the latter retaining the Bentley subdivision. Rolls-Royce Motors was subsequently sold to engineering conglomerate, Vickers and in 1998, Vickers sold Rolls-Royce to Volkswagen AG.

Intellectual property rights to both the name Rolls-Royce as well as the company’s logo had been retained not by Rolls-Royce Motors, but by aerospace company, Rolls-Royce Plc, which had continued to license both to the automotive division. Thus the sale of “Rolls-Royce” to VW included the Bentley name and logos, vehicle designs, model nameplates, production and administrative facilities, the Spirit of Ecstasy and Rolls-Royce grille shape trademarks (subsequently sold to BMW by VW)—but not the rights to the Rolls-Royce name or logo. The aerospace company, Rolls-Royce Plc, ultimately sold both to BMW AG.

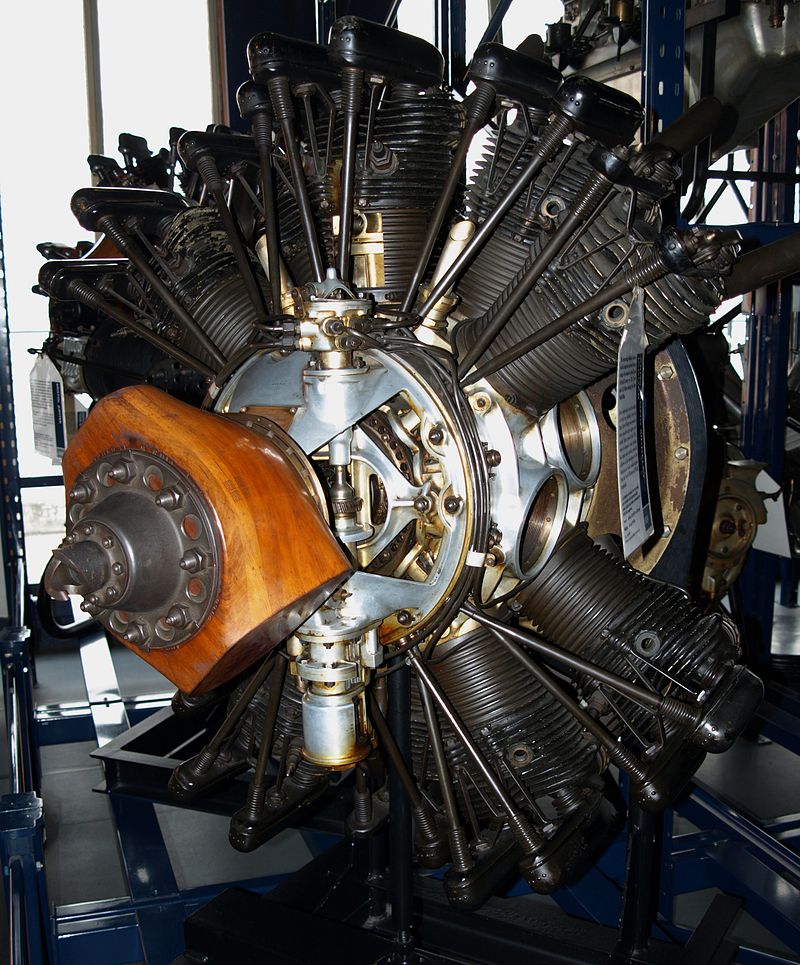

Cricklewood

Before World War I, Walter Owen Bentley and his brother, Horace Millner Bentley, sold French DFP cars in Cricklewood, North London, but W.O, as Walter was known, always wanted to design and build his own cars. At the DFP factory, in 1913, he noticed an aluminium paperweight and thought that aluminium might be a suitable replacement for cast iron to fabricate lighter pistons. The first Bentley aluminium pistons were fitted to Sopwith Camel aero engines during World War I.

In August 1919, W.O. registered Bentley Motors Ltd. and in October he exhibited a car chassis, with dummy engine, at the London Motor Show. Ex–Royal Flying Corps officer Clive Gallop designed an innovative four valves per cylinder engine for the chassis. By December the engine was built and running. Delivery of the first cars was scheduled for June 1920, but development took longer than estimated so the date was extended to September 1921. The durability of the first Bentley cars earned widespread acclaim and they competed in hill climbs and raced at Brooklands.

Bentley’s first major event was the 1922 Indianapolis 500, a race dominated by specialized cars with Duesenberg racing chassis. They entered a modified road car driven by works driver, Douglas Hawkes, accompanied by riding mechanic, H. S. “Bertie” Browning. Hawkes completed the full 500 miles and finished 13th with an average speed of 74.95 mph after starting in 19th position. The team was then rushed back to England to compete in the 1922 RAC Tourist Trophy.

Captain Woolf Barnato

In an ironic reference to his heavyweight boxer‘s stature, Captain Woolf Barnato was nicknamed “Babe“. In 1925, he acquired his first Bentley, a 3-litre. With this car he won numerous Brooklands races. Just a year later he acquired the Bentley business itself.

The Bentley enterprise was always underfunded, but inspired by the 1924 Le Mans win by John Duff and Frank Clement, Barnato agreed to finance Bentley’s business. Barnato had incorporated Baromans Ltd in 1922, which existed as his finance and investment vehicle. Via Baromans, Barnato initially invested in excess of £100,000, saving the business and its workforce. A financial reorganisation of the original Bentley company was carried out and all existing creditors paid off for £75,000. Existing shares were devalued from £1 each to just 1 shilling, or 5% or their original value. Barnato held 149,500 of the new shares giving him control of the company and he became chairman. Barnato injected further cash into the business: £35,000 secured by debenture in July 1927; £40,000 in 1928; £25,000 in 1929. With renewed financial input, W. O. Bentley was able to design another generation of cars.

The Bentley Boys

The Bentley Boys were a group of British motoring enthusiasts that included Barnato, Sir Henry “Tim” Birkin, steeple chaser George Duller, aviator Glen Kidston, automotive journalist S.C.H. “Sammy” Davis, and Dudley Benjafield. The Bentley Boys favoured Bentley cars. Many were independently wealthy and many had a military background. They kept the marque’s reputation for high performance alive; Bentley was noted for its four consecutive victories at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, from 1927 to 1930.

In 1929, Birkin developed the 4½-litre, lightweight Blower Bentley at Welwyn Garden City and produced five racing specials, starting with Bentley Blower No.1 which was optimised for the Brooklands racing circuit. Birkin overruled Bentley and put the model on the market before it was fully developed. As a result, it was unreliable.

In March 1930, during the Blue Train Races, Barnato raised the stakes on Rover and its Rover Light Six, having raced and beaten Le Train Bleu for the first time, to better that record with his 6½-litre Bentley Speed Six on a bet of £100. He drove against the train from Cannes to Calais, then by ferry to Dover, and finally London, travelling on public highways, and won.

Barnato drove his H.J. Mulliner–bodied formal saloon in the race against the Blue Train. Two months later, on 21 May 1930, he took delivery of a Speed Six with streamlined fastback “sportsman coupé” by Gurney Nutting. Both cars became known as the “Blue Train Bentleys“; the latter is regularly mistaken for, or erroneously referred to as being, the car that raced the Blue Train, while in fact Barnato named it in memory of his race. A painting by Terence Cuneo depicts the Gurney Nutting coupé racing along a road parallel to the Blue Train, which scenario never occurred as the road and railway did not follow the same route.

Cricklewood Bentleys

Bentley 8 Litre 4-door sports saloon

1924 Bentley 3-litre Sports Tourer by Park Ward 1921–1929 3-litre

1926–1930 4½-litre & “Blower Bentley”

1926–1930 4½-litre & “Blower Bentley”

1930 Bentley Speed Six tourer with original body by coachbuilder Hooper 1926–1930 6½-litre

1930 Bentley Speed Six tourer with original body by coachbuilder Hooper 1926–1930 6½-litre

1930 Speed Six Mulliner drophead coupé 1930 1928–1930 6½-litre Speed Six

1930 Speed Six Mulliner drophead coupé 1930 1928–1930 6½-litre Speed Six

1930 Bentley 8 Litre limousine by Mulliner 1930–1931 8-litre

1930 Bentley 8 Litre limousine by Mulliner 1930–1931 8-litre

1931 Bentley 4 Litre Supercharged Blower Two Seater Sports Vanden Plas 1931 4-litre

The original model was the three-litre, but as customers put heavier bodies on the chassis, a larger 4½-litre model followed. Perhaps the most iconic model of the period is the 4½-litre “Blower Bentley”, with its distinctive supercharger projecting forward from the bottom of the grille. Uncharacteristically fragile for a Bentley it was not the racing workhorse the 6½-litre was, though in 1930 Birkin remarkably finished second in the French Grand Prix at Pau in a stripped-down racing version of the Blower Bentley, behind Philippe Etancelin in

The 4½-litre model later became famous in popular media as the vehicle of choice of James Bond in the original novels, but this has been seen only briefly in the films. John Steed in the television series The Avengers also drove a Bentley.

The new eight-litre was such a success that when Barnato’s money seemed to run out in 1931 and Napier was planning to buy Bentley’s business, Rolls-Royce purchased Bentley Motors to prevent it from competing with their most expensive model, the Phantom II.

Performance at Le Mans

24 hours of Le Mans Grand Prix d’Endurance

- 1923 4th (private entry) (3-Litre)

- 1924 1st (3-Litre)

- 1925 did not finish

- 1926 did not finish

- 1927 1st 15th 17th (3-Litre)

- 1928 1st 5th (4½-litre)

- 1929 1st (Speed Six); 2nd 3rd 4th: (4½-litre)

- 1930 1st 2nd (Speed Six)

Bentley withdrew from motor racing just after winning at Le Mans in 1930, claiming that they had learned enough about speed and reliability.

Liquidation

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the resulting Great Depression throttled the demand for Bentley’s expensive motor cars. In July 1931, two mortgage payments were due which neither the company nor Barnato, the guarantor, were able to meet. On 10 July 1931 a receiver was appointed.

Napier offered to buy Bentley with the purchase to be final in November 1931. Instead, British Central Equitable Trust made a winning sealed bid of £125,000. British Central Equitable Trust later proved to be a front for Rolls-Royce Limited. Not even Bentley himself knew the identity of the purchaser until the deal was completed.

Barnato received £42,000 for his shares in Bentley Motors. In 1934 he was appointed to the board of the new Bentley Motors (1931) Ltd. In the same year Bentley confirmed that it would continue racing.

Derby and Rolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce took over the assets of Bentley Motors (1919) Ltd and formed a subsidiary, Bentley Motors (1931) Ltd. Rolls-Royce had acquired the Bentley showrooms in Cork Street, the service station at Kingsbury, the complex at Cricklewood and the services of Bentley himself. This last was disputed by Napier in court without success. Bentley had neglected to register their trademark so Rolls-Royce immediately did so. They also sold the Cricklewood factory in 1932. Production stopped for two years, before resuming at the Rolls-Royce works in Derby. Unhappy with his role at Rolls-Royce, when his contract expired at the end of April 1935 W. O. Bentley left to join Lagonda.

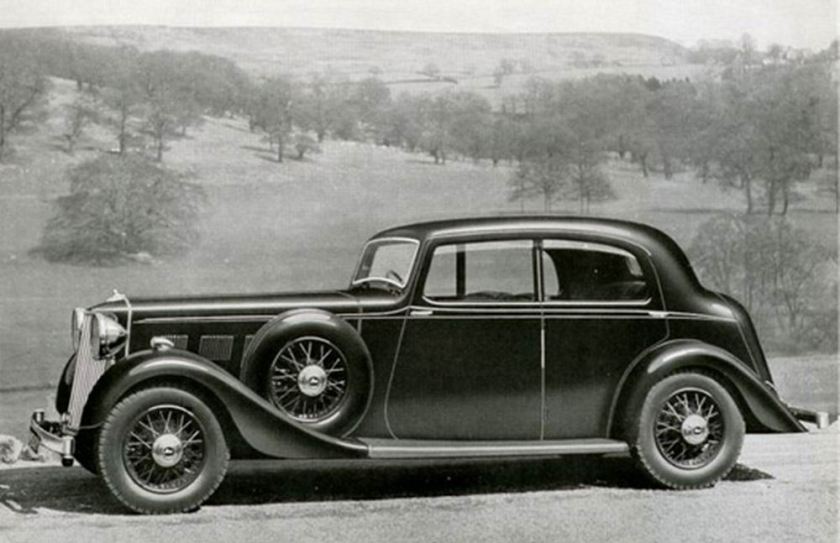

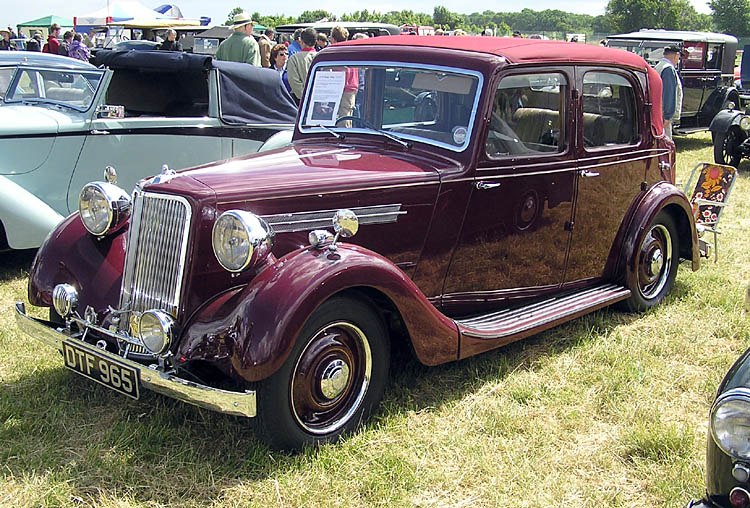

When the new Bentley 3½ litre appeared in 1933, it was a sporting variant of the Rolls-Royce 20/25, which disappointed some traditional customers yet was well received by many others. W. O. Bentley was reported as saying, “Taking all things into consideration, I would rather own this Bentley than any other car produced under that name”. Rolls-Royce’s advertisements for the 3 1⁄2 Litre called it “the silent sports car”, a slogan Rolls-Royce continued to use for Bentley cars until the 1950s.

All Bentleys produced from 1931 to 2004 used inherited or shared Rolls-Royce chassis, and adapted Rolls-Royce engines, and are described by critics as badge-engineered Rolls-Royces.

Derby Bentleys

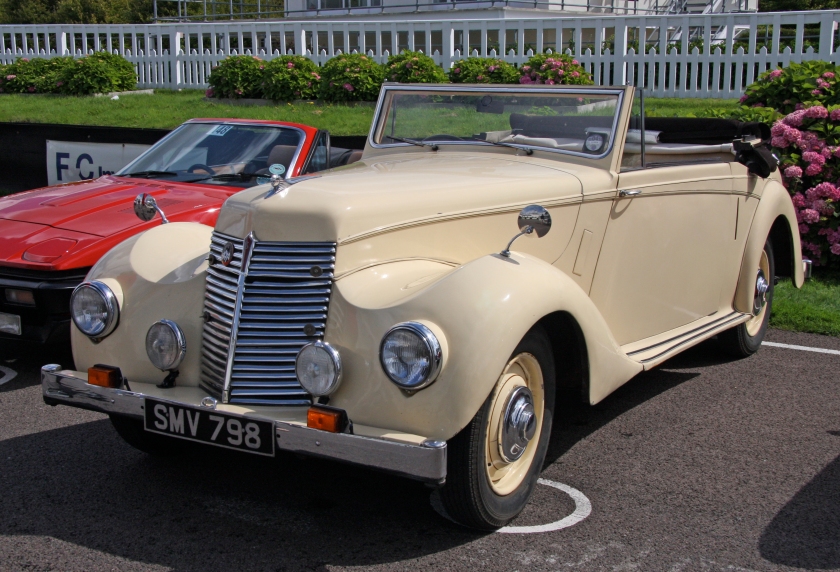

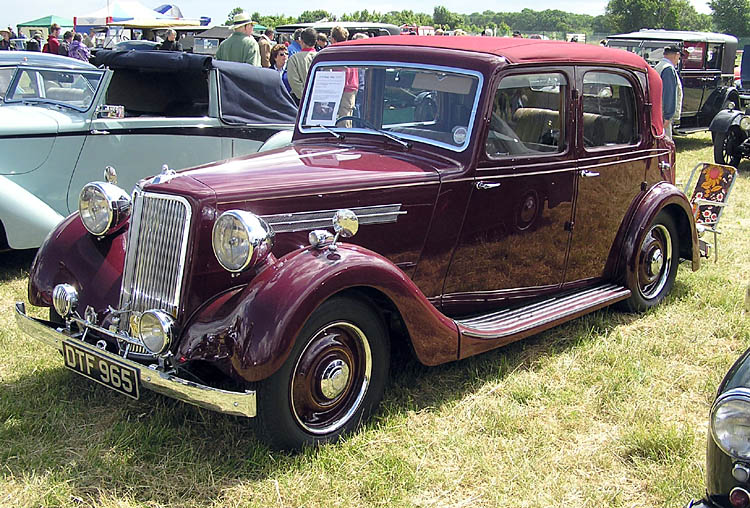

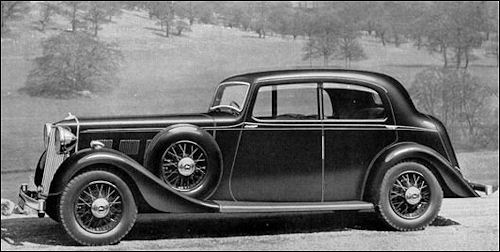

1935 Bentley 3½ sedan Park Ward body 1933–1937 3½-litre

1936 Bentley 4¼-litre 4-door sports saloon 1936–1939 4¼-litre

1936 Bentley 4¼-litre 4-door sports saloon 1936–1939 4¼-litre

Bentley Mark V B-24-AW 1939–1941 Mark V

1939 Mark V

1939 Mark V

Crewe and Rolls-Royce

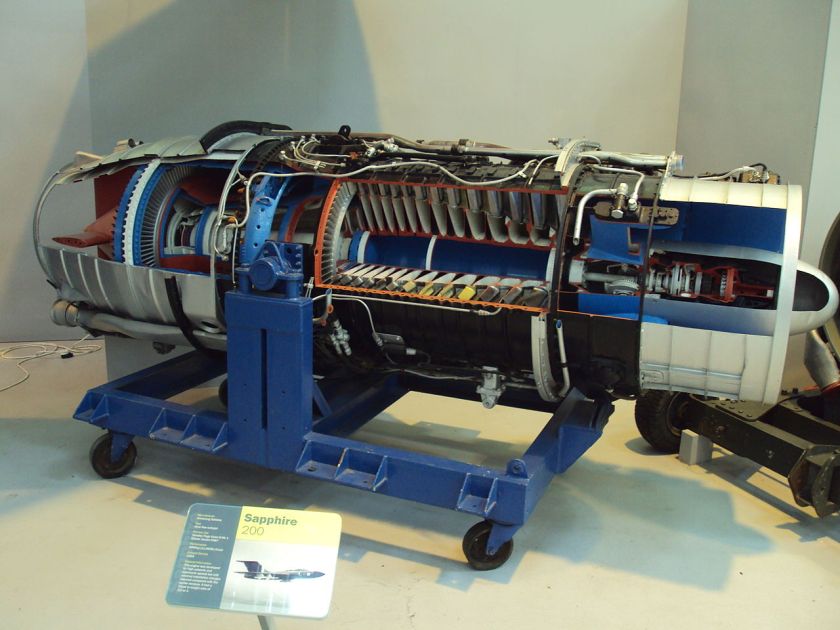

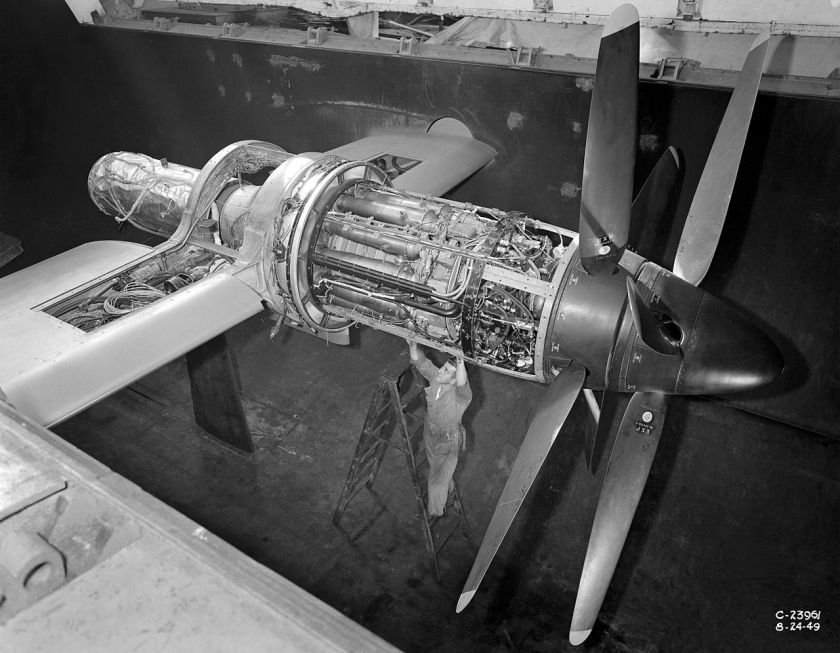

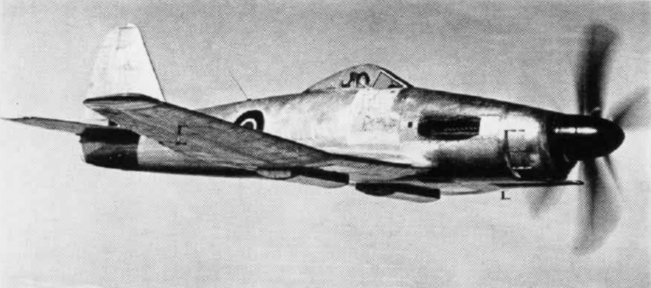

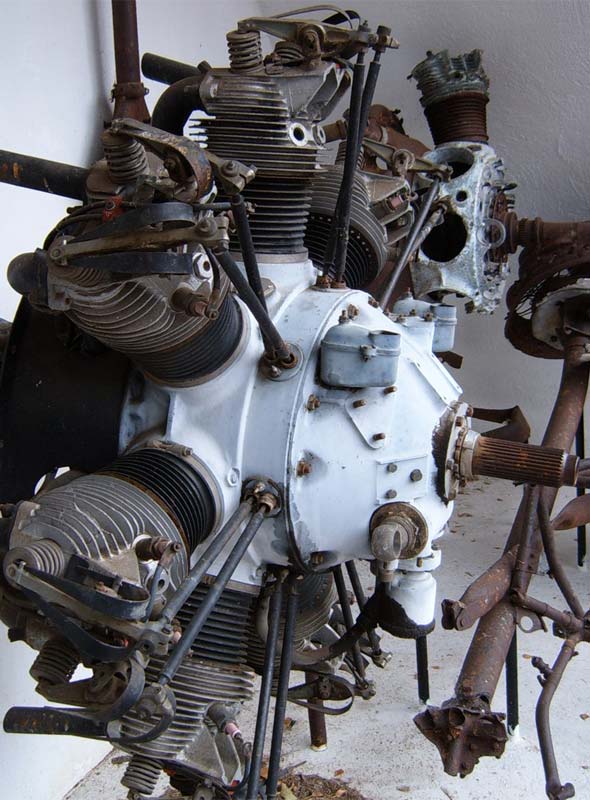

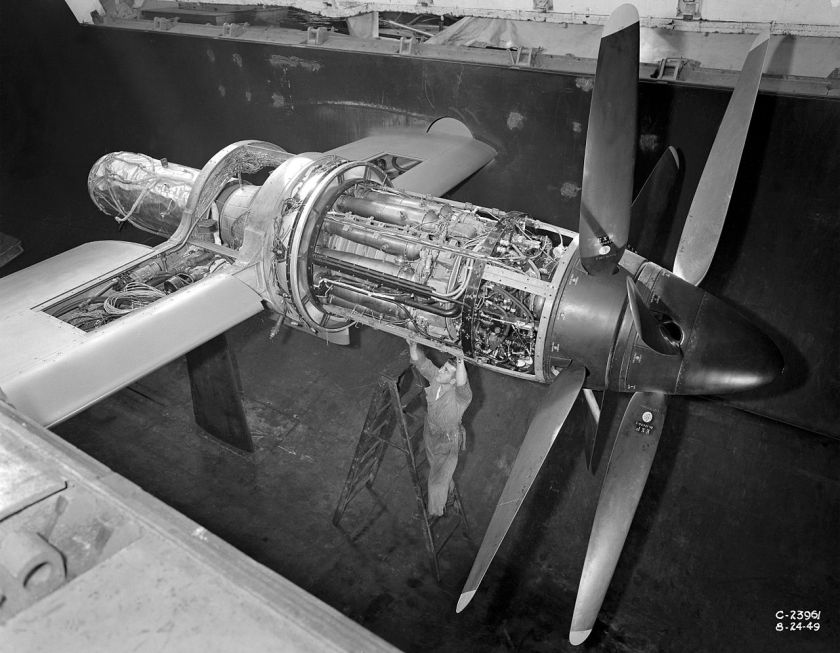

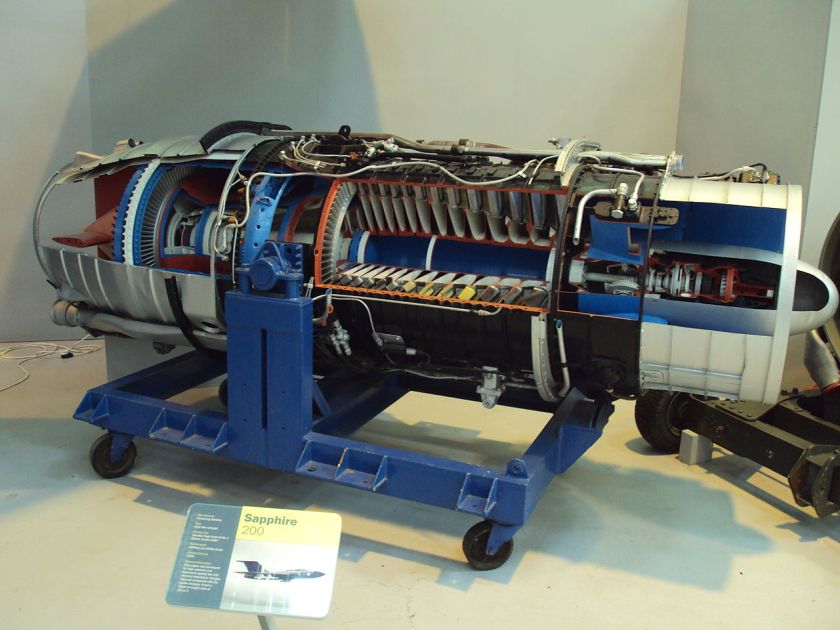

In preparation for war, Rolls-Royce and the British Government searched for a location for a shadow factory to ensure production of aero-engines. Crewe, with its excellent road and rail links, as well as being located in the northwest away from the aerial bombing starting in mainland Europe, was a logical choice. Crewe also had extensive open farming land. Construction of the factory started on a 60-acre area on the potato fields of Merrill’s Farm in July 1938, with the first Rolls-Royce Merlin aero-engine rolling off the production line five months later. 25,000 Merlin engines were produced and at its peak, in 1943 during World War II, the factory employed 10,000 people. With the war in Europe over and the general move towards the then new jet engines, Rolls-Royce concentrated its aero engine operations at Derby and moved motor car operations to Crewe.

Standard Steel saloons

Bentley Mark VI standard steel saloon, the first Bentley supplied by Rolls-Royce with a standard all-steel body.

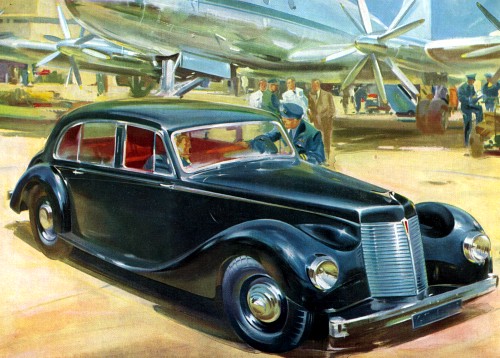

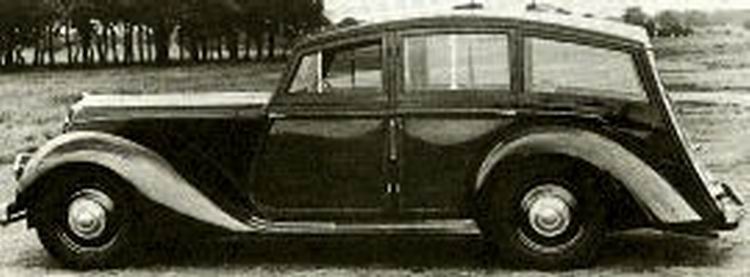

Until some time after World War II, most high-end motorcar manufacturers like Bentley and Rolls-Royce did not supply complete cars. They sold rolling chassis, near-complete from the instrument panel forward. Each chassis was delivered to the coach builder of the buyer’s choice. The biggest specialist car dealerships had coachbuilders build standard designs for them which were held in stock awaiting potential buyers.

To meet post-war demand, particularly UK Government pressure to export and earn overseas currency, Rolls-Royce developed an all steel body using pressings made by Pressed Steel to create a “standard” ready-to-drive complete saloon car. The first steel-bodied model produced was the Bentley Mark VI: these started to emerge from the newly reconfigured Crewe factory early in 1946. Some years later, initially only for export, the Rolls-Royce Silver Dawn was introduced, a standard steel Bentley but with a Rolls-Royce radiator grille for a small extra charge, and this convention continued.

Chassis remained available to coachbuilders until the end of production of the Bentley S3, which was replaced for October 1965 by the chassis-less monocoque construction T series.

Bentley Continental

The Continental fastback coupé was aimed at the UK market, most cars, 164 plus a prototype, being right-hand drive. The chassis was produced at the Crewe factory and shared many components with the standard R type. Other than the R-Type standard steel saloon, R-Type Continentals were delivered as rolling chassis to the coachbuilder of choice. Coachwork for most of these cars was completed by H. J. Mulliner & Co. who mainly built them in fastback coupe form. Other coachwork came from Park Ward (London) who built six, later including a drophead coupe version. Franay (Paris) built five, Graber (Wichtrach, Switzerland) built three, one of them later altered by Köng (Basel, Switzerland), and Pininfarina made one. James Young (London) built in 1954 a Sports Saloon for the owner of James Young’s, James Barclay.

The early R Type Continental has essentially the same engine as the standard R Type, but with modified carburation, induction and exhaust manifolds along with higher gear ratios. After July 1954 the car was fitted with an engine, having now a larger bore of 94.62 mm (3.7 in) with a total displacement of 4,887 cc (4.9 L; 298.2 cu in). The compression ratio was raised to 7.25:1.

Crewe Rolls-Royce Bentleys

- Bentleys made by Rolls-Royce Ltd. in Crewe

-

Bentley S-series Standard Saloon

-

Bentley T-series Standard Saloon (l.w.b.)

Standard-steel saloon

- 1947 Bentley Mark VI early production (DVLA) first registered 28 October 1947, 4257cc

Bentley Mark VI early production (DVLA) first registered 28 October 1947, 4257cc

Bentley Mark VI early production (DVLA) first registered 28 October 1947, 4257cc - 1946–52 Mark VI

1953 Bentley Mark VII R-Type standard steel saloon 1952–55 R Type Continental

1953 Bentley Mark VII R-Type standard steel saloon 1952–55 R Type Continental- 1954 Bentley R-Type Continental HJ Mulliner Sports Saloon – chassis BC2LC 1954 Bentley R-Type Continental HJ Mulliner Sports Saloon – chassis BC2LC 1954 Bentley R-Type Continental HJ Mulliner Sports Saloon – chassis BC2LC

1954 Bentley R-Type Continental HJ Mulliner Sports Saloon – chassis BC2LC

1954 Bentley R-Type Continental HJ Mulliner Sports Saloon – chassis BC2LC - 1952–55 R Type Continental

- S-series

-

Bentley S1 1955–59 S1 and

Bentley S1 1955–59 S1 and

- 1957 Bentley S1 Continental, #BC27CH, Park Ward coupé (DVL) first registered 18 June 1957, 4887cc Continental

Bentley S2

Bentley S2

- Bentley Continental S2

- 1959–62 S2 and Continental

- Bentley S3

- Bentley S3 Continental Flying Spur by HJ Mulliner 1962–65 S3 and Continental

- T-series

- 1967 Bentley T1 Coupé 1965–77 T1

- 1977 Bentley T2 1977–80 T2

1971–84 Corniche

1971–84 Corniche 1975–86 Camargue

1975–86 Camargue

Crewe and Vickers

The problems of Bentley’s owner with Rolls-Royce aero engine development, the RB211, brought about the financial collapse of its business in 1970.

The motorcar division was made a separate business, Rolls-Royce Motors Limited, which remained independent until bought by Vickers plc in August 1980. By the 1970s and early 1980s Bentley sales had fallen badly; at one point less than 5% of combined production carried the Bentley badge. Under Vickers, Bentley set about regaining its high-performance heritage, typified by the 1980 Mulsanne. Bentley’s restored sporting image created a renewed interest in the name and Bentley sales as a proportion of output began to rise. By 1986 the Bentley: Rolls-Royce ratio had reached 40:60; by 1991 it achieved parity.

Crewe Vickers Bentleys

1984–95 Continental: convertible

1984–95 Continental: convertible Bentley Continental T 1996–2002 Continental T

Bentley Continental T 1996–2002 Continental T 2001 Bentley Continental R Mulliner 1999–2003 Continental R Mulliner: performance model

2001 Bentley Continental R Mulliner 1999–2003 Continental R Mulliner: performance model 1992–98 Brooklands: improved Eight

1992–98 Brooklands: improved Eight 1998 Bentley-Brooklands-R-Mulliner-Car-12-of-100-WCH66811-3 1996–98 Brooklands R: performance Brooklands

1998 Bentley-Brooklands-R-Mulliner-Car-12-of-100-WCH66811-3 1996–98 Brooklands R: performance BrooklandsVolkswagen AG vs. BMW AG

In October 1997, Vickers announced that it had decided to sell Rolls-Royce Motors. BMW AG seemed to be a logical purchaser because BMW already supplied engines and other components for Bentley and Rolls-Royce branded cars and because of BMW and Vickers joint efforts in building aircraft engines. BMW made a final offer of £340m, but was outbid by Volkswagen AG, which offered £430m. Volkswagen AG acquired the vehicle designs, model nameplates, production and administrative facilities, the Spirit of Ecstasy and Rolls-Royce grille shape trademarks, but not the rights to the use of the Rolls-Royce name or logo, which are owned by Rolls-Royce Holdings plc. In 1998, BMW started supplying components for the new range of Rolls-Royce and Bentley cars—notably V8 engines for the Bentley Arnage and V12 engines for the Rolls-Royce Silver Seraph, however, the supply contract allowed BMW to terminate its supply deal with Rolls-Royce with 12 months’ notice, which would not be enough time for Volkswagen to re-engineer the cars.

BMW paid Rolls-Royce plc £40m to license the Rolls-Royce name and logo. After negotiations, BMW and Volkswagen AG agreed that, from 1998 to 2002, BMW would continue to supply engines and components and would allow Volkswagen temporary use of the Rolls-Royce name and logo. All BMW engine supply ended in 2003 with the end of Silver Seraph production.

From 1 January 2003 forward, Volkswagen AG would be the sole provider of cars with the “Bentley” marque. BMW established a new legal entity, Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited, and built a new administrative headquarters and production facility for Rolls-Royce branded vehicles in Goodwood, West Sussex, England.

Modern Bentleys

The Bentley line-up from late 2000s (from left): Flying Spur, Continental GT, and Arnage

After acquiring the business, Volkswagen spent GBP 500 million (about US$845 million) to modernise the Crewe factory and increase production capacity. As of early 2010, there are about 3,500 working at Crewe, compared with about 1,500 in 1998 before being taken over by Volkswagen. It was reported that Volkswagen invested a total of nearly US$2 billion in Bentley and its revival. As a result of upgrading facilities at Crewe the bodywork now arrives fully painted at the Crewe facility for final assembly, with the parts coming from Germany—similarly Rolls-Royce body shells are painted and shipped to the UK for assembly only.

In 2002, Bentley presented Queen Elizabeth II with an official State Limousine to celebrate her Golden Jubilee. In 2003, Bentley’s two-door convertible, the Bentley Azure, ceased production, and Bentley introduced a second line, Bentley Continental GT, a large luxury coupé powered by a W12 engine built in Crewe.

Demand had been so great that the factory at Crewe was unable to meet orders despite an installed capacity of approximately 9,500 vehicles per year; there was a waiting list of over a year for new cars to be delivered. Consequently, part of the production of the new Flying Spur, a four-door version of the Continental GT, was assigned to the Transparent Factory (Germany), where the Volkswagen Phaeton luxury car is also assembled. This arrangement ceased at the end of 2006 after around 1,000 cars, with all car production reverting to the Crewe plant.

In April 2005, Bentley confirmed plans to produce a four-seat convertible model—the Azure, derived from the Arnage Drophead Coupé prototype—at Crewe beginning in 2006. By the autumn of 2005, the convertible version of the successful Continental GT, the Continental GTC, was also presented. These two models were successfully launched in late 2006.

A limited run of a Zagato modified GT was also announced in March 2008, dubbed “GTZ“.

A new version of the Bentley Continental was introduced at the 2009 Geneva Auto Show: The Continental Supersports. This new Bentley is a supercar combining extreme power with environmentally friendly FlexFuel technology, capable of using petrol (gasoline) and biofuel (E85 ethanol).

Bentley sales continued to increase, and in 2005 8,627 were sold worldwide, 3,654 in the United States. In 2007, the 10,000 cars-per-year threshold was broken for the first time with sales of 10,014. For 2007, a record profit of €155 million was also announced. Bentley reported a sale of about 7,600 units in 2008. However, its global sales plunged 50 percent to 4,616 vehicles in 2009 (with the U.S. deliveries dropped 49% to 1,433 vehicles) and it suffered an operating loss of €194 million, compared with an operating profit of €10 million in 2008. As a result of the slump in sales, production at Crewe was shut down during March and April 2009. Though vehicle sales increased by 11% to 5,117 in 2010, operating loss grew by 26% to €245 million. In Autumn 2010, workers at Crewe staged a series of protests over proposal of compulsory work on Fridays and mandatory overtime during the week.

Vehicle sales in 2011 rose 37% to 7,003 vehicles, with the new Continental GT accounting for over one-third of total sales. The current workforce is about 4,000 people.

The business earned a profit in 2011 after two years of losses as a result of the following sales results:

Unsold cars: During the years 2011 and 2012 production exceeded deliveries by 1,187 cars which is estimated to have trebled inventory.

Car models, Crewe Volkswagen

Car models in production

2010–present: Mulsanne

2010–present: Mulsanne

2011–present: Continental GT (Gen 2)

2011–present: Continental GT (Gen 2)

2011–present: Continental GT Convertible (Gen 2)

2011–present: Continental GT Convertible (Gen 2)

2013–present: Flying Spur

2013–present: Flying Spur

2016–present: Bentayga

2016–present: Bentayga

2018–????: Continental GT (Gen 3)

2018–????: Continental GT (Gen 3)

Former car models in production

1992-2011: Bentley Brooklands

1992-2011: Bentley Brooklands

1998-2003: Arnage

1998-2003: Arnage

1995-2009: Azure

1995-2009: Azure

2003-2011: Continental GT

2003-2011: Continental GT

2005-2012: Continental Flying Spur

2005-2012: Continental Flying Spur

2006-2011: Continental GTC

2006-2011: Continental GTC

2009-2009: Continental Supersports

2009-2009: Continental Supersports

2009-2009: Bentley Zagato GTZ

2009-2009: Bentley Zagato GTZ

Former special edition car models in production

1999: Hunaudieres Concept

1999: Hunaudieres Concept

2002: State Limousine

2002: State Limousine

My complete collection off pictures all from the World Wide Web:

Motorsport

A Bentley Continental GT3 entered by the M-Sport factory team won the Silverstone round of the 2014 Blancpain Endurance Series. This was Bentley’s first official entry in a British race since the 1930 RAC Tourist Trophy.

References

- Jump up^ Volkswagen AG 2012, p. 68.

- Jump up^ Volkswagen AG 2012, p. 49.

- Jump up^ “Bentley Motors Website: World of Bentley: Our Story: News: 2014: Wolfgang Dürheimer to become Bentley CEO”. Bentleymotors.com. 15 April 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Jump up^ https://www.bentleymedia.com/en/newsitem/654

- Jump up^ http://www.msn.com/en-us/tv/news/the-new-bentley-continental-gt-darren-day-head-of-interior-design-bentley-motors/vp-AAs6XKD

- Jump up^ Volkswagen AG 2012, p. 102.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Volkswagen AG 2012a, p. 120.

- Jump up^ “vwagfy2012”.

- Jump up^ Volkswagen AG 2012a, p. 121.

- Jump up^ Armistead, Louise (9 October 2013). “Video: behind the scenes at the Bentley factory”. The Daily Telegraph. London.

- Jump up^ Volkswagen AG 2012, p. 19.

- Jump up^ “Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft Facts and Figures 2012” (PDF). volkswagenag.com. Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft. 11 June 2012. 1058.809.453.20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Jump up^ “Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft Annual Report 2011” (PDF). volkswagenag.com. Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft. 12 March 2012. 258.809.536.00. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- Jump up^ Armitstead, Louise (6 October 2013). “Monday Interview: Bentley boss on what’s driving demand for luxury British cars”. London: The Telegraph. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- Jump up^ Einhorn, Bruce (5 April 2012). “The Surge in China’s Auto Sales May Soon Slow”. Bloomberg Businessweek.

- Jump up^ “BENTLEY: MADE IN GERMANY”. PistonHeads. 14 November 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Georgano, Nick, ed. (1 October 2000). Beaulieu Encyclopedia of the Automobile (Hardcover, Reprint ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 1-57958-293-1.

- Jump up^ “Bentley’s racing heritage”. The Telegraph. 5 October 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wagstaff, Ian (September 2010). “3: The Not-So-Roaring Twenties”. The British at Indianapolis=. Dorchester, UK: Veloce Publishing. pp. .26–27. ISBN 978-1-84584-246-8. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

It was an event that was to prove a costly exercise for the Cricklewood-based company in sending both a professional driver and a mechanic with the car.

- Jump up^ Davidson, Donald; Schaffer, Rick (2006). “Official Box Scores 1911–2006”. Autocourse Official History of the Indianapolis 500. St. Paul, MN USA: MBI Publishing. p. 327. ISBN 1-905334-20-6. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- Jump up^ Davidson, Donald, Schaffer, Rick, Autocourse Official History of the Indianapolis 500, page 60

- Jump up^ Melissen, Wouter (12 January 2004). “Bentley Speed Six ‘Blue Train Special'”. UltimateCarPage. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- Jump up^ Burgess-Wise, David (1 January 2006). “The Slippery Shape of Power”. Auto Aficionado. Archived from the original on 24 March 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- Jump up^ “Bentley Motors To Give Up Racing”. Evening Telegraph. Angus, Scotland: British Newspaper Archive. 1 July 1930. Retrieved 23 July 2014. (Subscription required (help)).

- Jump up^ “Receiver Appointed Of Bentley Motors Limited Re Bentley Motors Limited; London Life Association Limited v. Bentley Motors Limited, And Woolf Barnato”. The Times, Saturday, 11 July 1931; p. 4; Issue 45872

- Jump up^ Feast, Richard (2004). “When Barnato bought Bentley”. The DNA of Bentley. St. Paul, MN: MotorBooks International. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-7603-1946-8. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- Jump up^ Finley, Ross (29 November 1985). “Luxury of the long-distance cruiser”. Glasgow Herald. p. 21. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- Jump up^ Feast, Richard, The DNA of Bentley, Chapter 5: “Togetherness: Rolls-Royce/Bentley”, p. 77

- Jump up^ Stein, Ralph (1952). Sports Cars of the World. Scribner. p. 43. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

These, known as “the silent sports car,” have been successfully marketed for almost twenty years now in various models.

- Jump up^ Sewell, Brian (13 July 2004). “New Bentley is a drive in the wrong direction”. The Independent. London. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Crewe’s Rolls-Royce Factory From Old Photographs by Peter Ollerhead and Tony Flood, republished electronically 2013 by Amberley Publishing of Stroud, Gloucestershire, England

- Jump up^ Pugh 2000, pp. 192-198.

- Jump up^ “Bentley Crewe History 1914 – 2006”. Jack Barclay. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- Jump up^ Ollerhead, P. (2013). Crewe’s Rolls-Royce Factory From Old Photographs. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445627649. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- Jump up^ “Used Car test: Bentley Continental”. Autocar. 130 (3824): 47–48. 29 May 1969.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cremer, Andreas (24 June 2010). “Volkswagen Said to Shuffle Porsche, Bentley Managers”. BusinessWeek. Retrieved 25 June2010.

- Jump up^ Gillies, Mark (10 May 2010). “Going Back in Time at the Bentley Factory”. Car and Driver blog. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- Jump up^ Edmondson, Gail (6 December 2004). “VW Steals A Lead In Luxury”. BusinessWeek. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- Jump up^ Garlick. “Bentley reports record profit”. Retrieved 18 March2008.

- Jump up^ Reiter, Chris; Ramsey, Mike (15 December 2009). “Daimler Maybach Fails to Dent Rolls, Bentley Super-Luxury Lead”. Bloomberg.

- Jump up^ Cremer, Andreas (14 January 2010). “Volkswagen’s Bentley Targets U.S. Growth With Mulsanne Sedan”. BusinessWeek. Retrieved 25 June 2010.[dead link]

- Jump up^ Massey, Ray (23 January 2009). “Bentley announces seven-week production shutdown while Jaguar chief calls for Government aid”. Daily Mail. London.

- Jump up^ “Volkswagen AG 2010 Annual Report”. Annualreport2010.volkswagenag.com. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- Jump up^ Cooke, Rhiannon (24 October 2010). “Bentley protests continue in Crewe over changes to working hours”. Crewe Chronicle.

- Jump up^ Rauwald, Christopher (4 January 2012). “Bentley Mulls Its Own SV”. The Wall Street Journal. p. B3.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Volkswagen AG 2012 Annual Report”. Annualreport2012.volkswagenag.com. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- Jump up^ Ramsey, Jonathon (2009). “First Bentley Zagato GTZ available at $1.7M”. autoblog.com. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- Jump up^ Burt, Matt (25 May 2014). “New Bentley Continental GT3 claims inaugural victory at Silverstone”. Autocar. Haymarket Group. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

See also

Further reading

Richard Feast, Kidnap of the Flying Lady: How Germany Captured Both Rolls Royce and Bentley, Motorbooks, ISBN0-7603-1686-4

External links

| Rolls-Royce vehicles. |

2001 Bentley Arnage Red Label

2001 Bentley Arnage Red Label

2010 Bentley Mulsanne

2010 Bentley Mulsanne

1984 Bentley Mulsanne Turbo

1984 Bentley Mulsanne Turbo

Bentley Continental S (1994-95)

Bentley Continental S (1994-95)

#######

#######