Packard

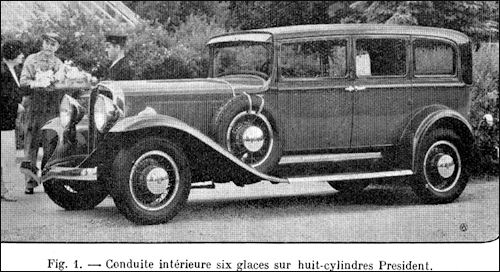

Packard was an American luxury automobile marque built by the Packard Motor Car Company of Detroit, Michigan, and later by the Studebaker-Packard Corporation of South Bend, Indiana. The first Packard automobiles were produced in 1899, and the last in 1958.

History

1899–1905

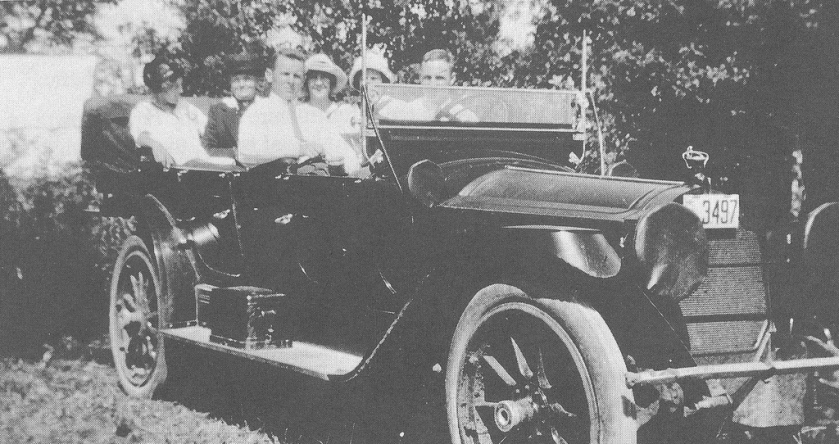

Packard was founded by James Ward Packard, his brother William Doud Packard and their partner, George Lewis Weiss, in the city of Warren, Ohio where 400 Packard automobiles were built at their Packard factory on Dana Street Northeast, from 1899 to 1903. Being a mechanical engineer, James Ward Packard believed they could build a better horseless carriage than the Winton cars owned by Weiss, an important Winton stockholder.

In September, 1900, the Ohio Automobile Company was founded to produce “Packard” autos. Since these automobiles quickly gained an excellent reputation, the name was changed on October 13, 1902 to the Packard Motor Car Company.

All Packards had a single-cylinder engine until 1903. From the very beginning, Packard featured innovations, including the modern steering wheel and, years later, the first production 12-cylinder engine and air-conditioning in a passenger car.

While the Black Motor Company‘s “Black” went as low as $375, Western Tool Works‘ Gale Model A roadster was $500, the high-volume Oldsmobile Runabout went for $650, and the Cole 30 and Cole Runabout were US$1,500, Packard concentrated on cars with prices starting at $2,600. The marque developed a following among wealthy purchasers both in the United States and abroad.

Henry Bourne Joy, a member of one of Detroit‘s oldest and wealthiest families, bought a Packard. Impressed by its reliability, he visited the Packards and soon enlisted a group of investors—including Truman Handy Newberry and Russell A. Alger Jr. On October 2, 1902, this group refinanced and renamed the New York and Ohio Automobile Company as “Packard Motor Car Company”, with James as president. Alger later served as vice-president. Packard moved its automobile operation to Detroit soon after, and Joy became general manager, later to be chairman of the board. An original Packard, reputedly the first manufactured, was donated by a grateful James Packard to his alma mater, Lehigh University, and is preserved there in the Packard Laboratory. Another is on display at the Packard Museum in Warren, Ohio.

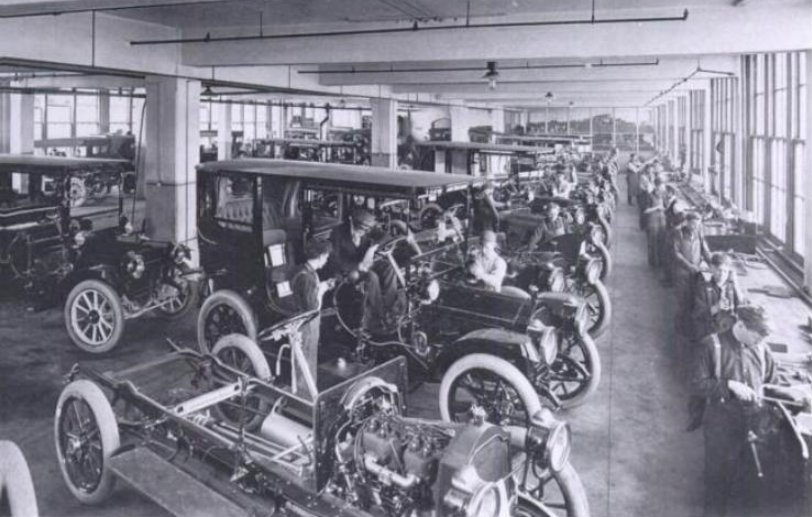

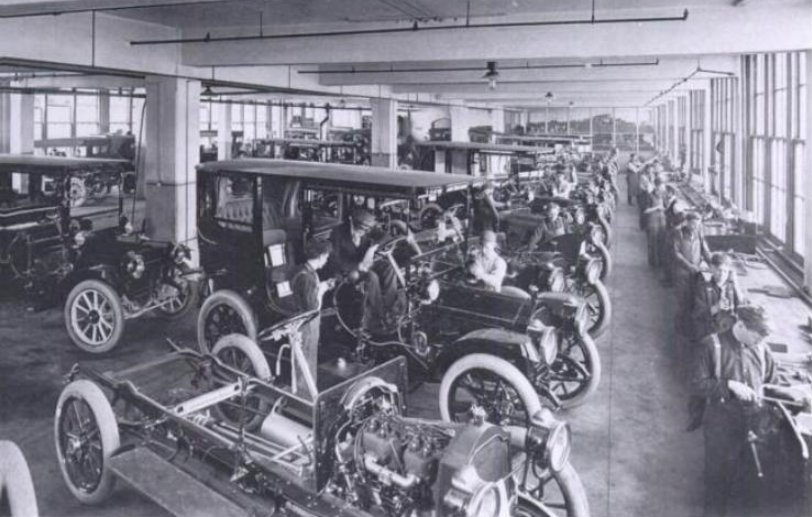

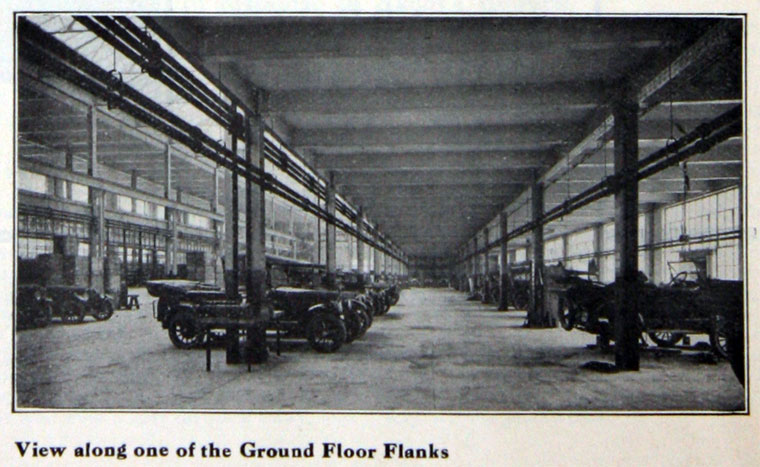

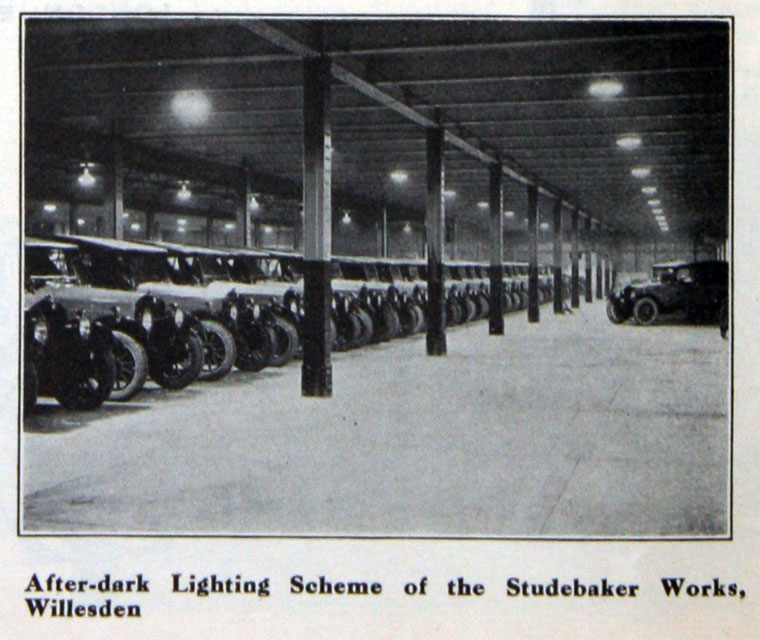

The 3,500,000 sq ft (330,000 m2) Packard plant on East Grand Boulevard in Detroit was located on over 40 acres (16 ha) of land. Designed by Albert Kahn Associates, it included the first use of reinforced concrete for industrial construction in Detroit and was considered the most modern automobile manufacturing facility in the world when opened in 1903. Its skilled craftsmen practiced over eighty trades. The dilapidated plant still stands, despite repeated fires. Architect Kahn also designed the Packard Proving Grounds at Utica, Michigan.

1899-1930

1899 Packard Model A Runabout, Wagen Nr. 1 (Werkbild, Anfang November 1899)

1903 Packard Modell F, Einzylinder

1904 Packard Model L

1905 Packard Twin Six 905

1906 Packard Modell 18 Runabout (Serie NA)

1906 Packard S 24HP Runabout

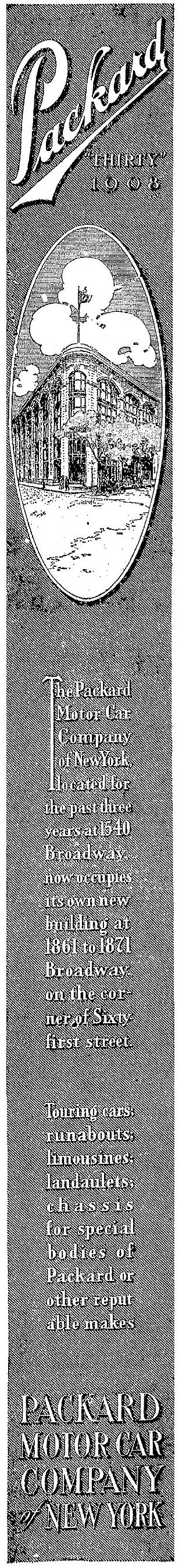

1907 Packard ad The New York Times 1907-11-06

1910 Packard Advertisement – Indianapolis Star, May 22, 1910

1910 Packard Advertisement – Indianapolis Star, May 22, 1910

1910 Packard Eighteen Touring Serie NB

1910 Providence Packard

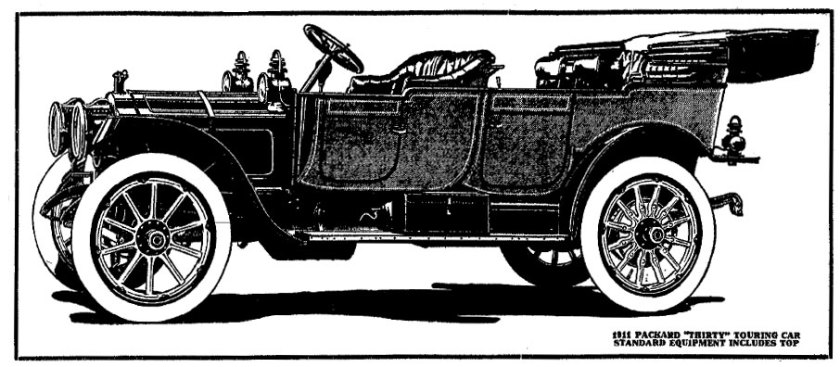

1911 Packard

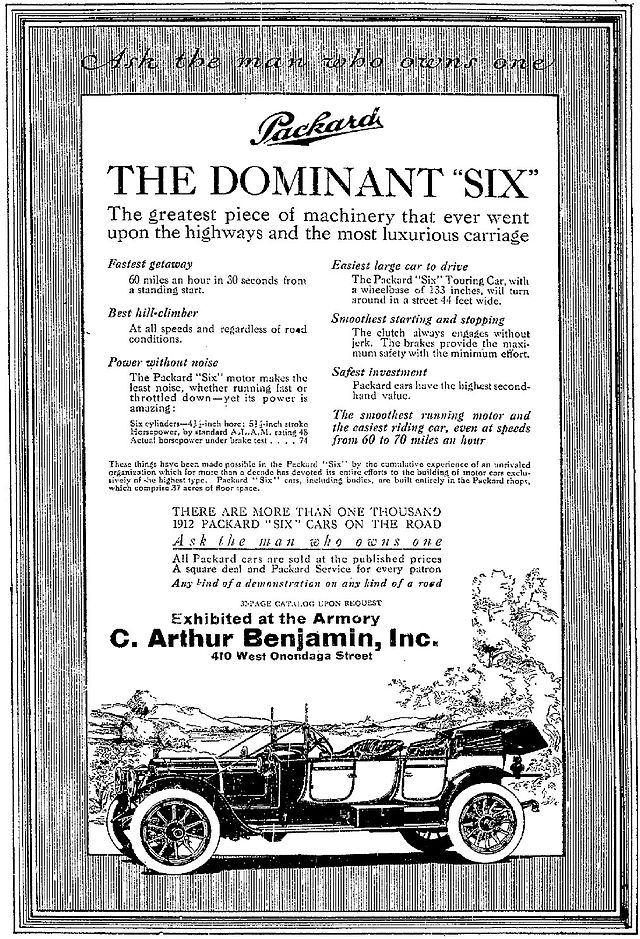

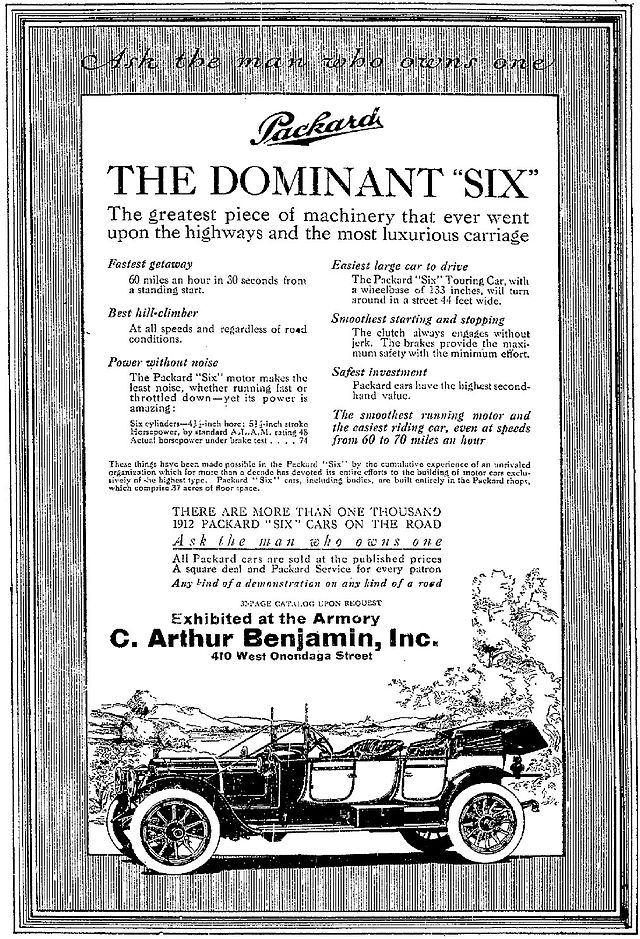

1912 Packard Advertisement – Syracuse Herald, March 14, 1912

1913 Packard 6

1914 Packard 1-38 Five Passenger Phaeton

1914-packard-dominant-six-4-48-runabout

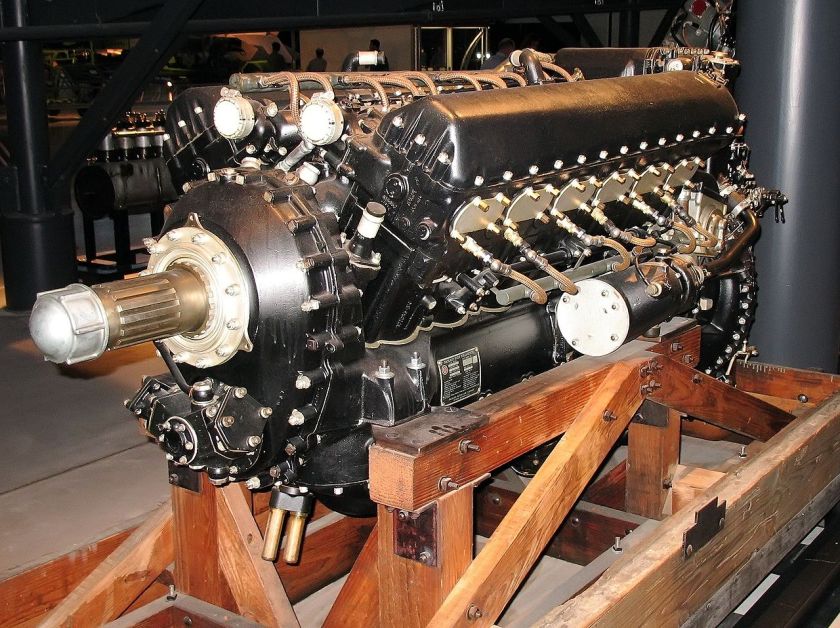

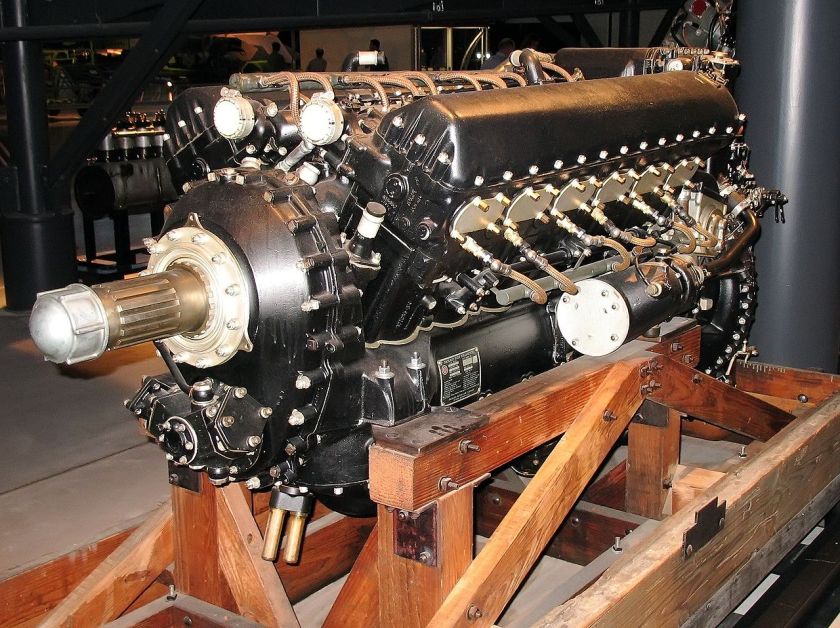

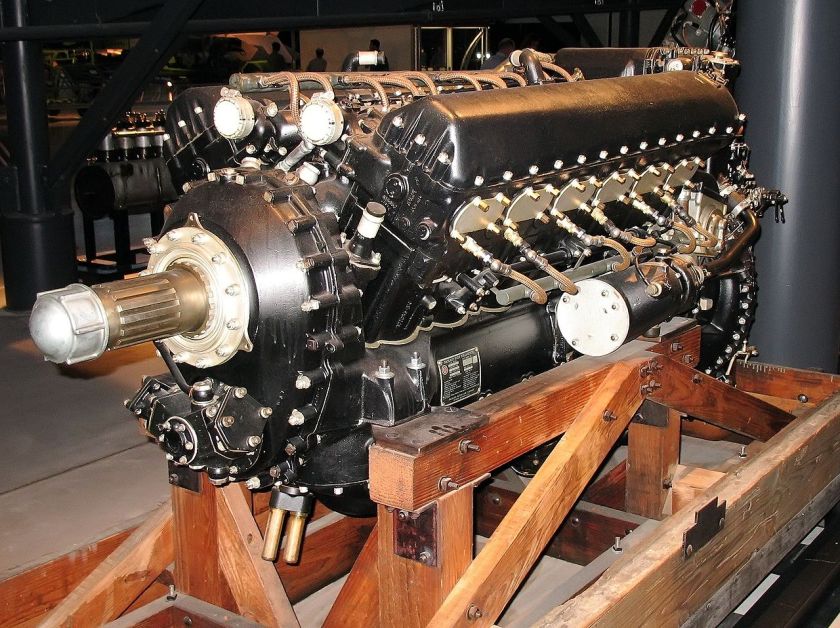

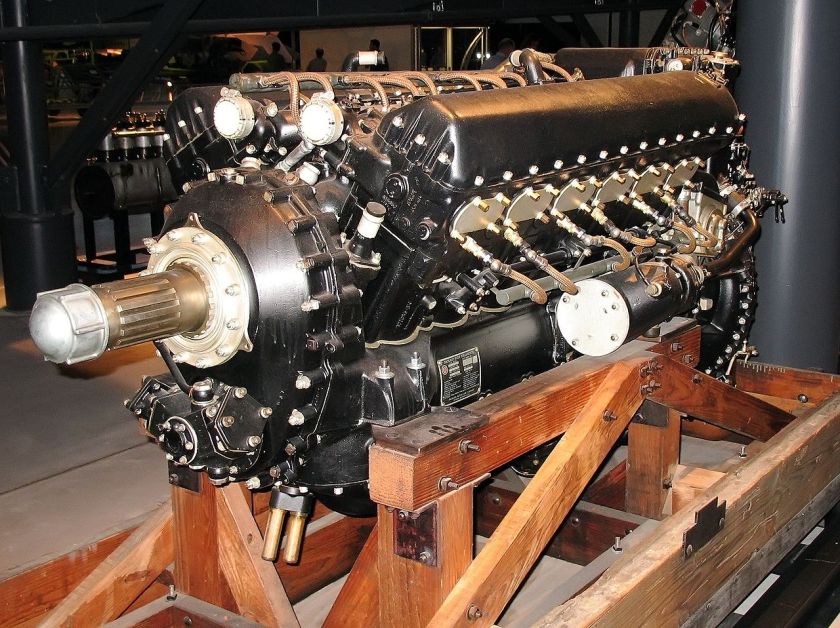

1915-ox5-aircraft-engine-packard-merlin

Kampfflugzeugmotor Packard V-1650-7 Weiterentwicklung unter Lizenz des Rolls-Royce Merlin V12 Zylinder, in dieser Version 1315 bhp

1915-packard-model-e-7t

1915-packard

1916-packard-first-series-twin-six-touring-1-35

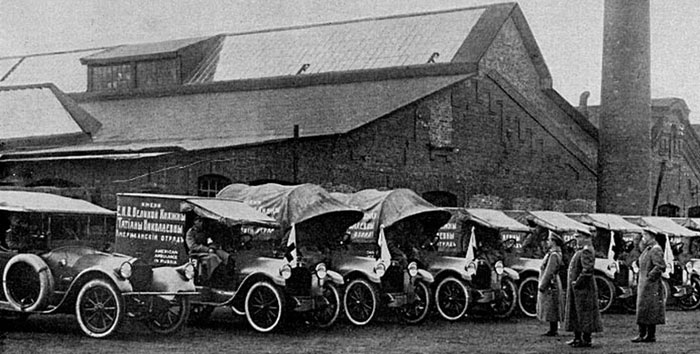

1916-packard-model-d-mexican-revolution-231

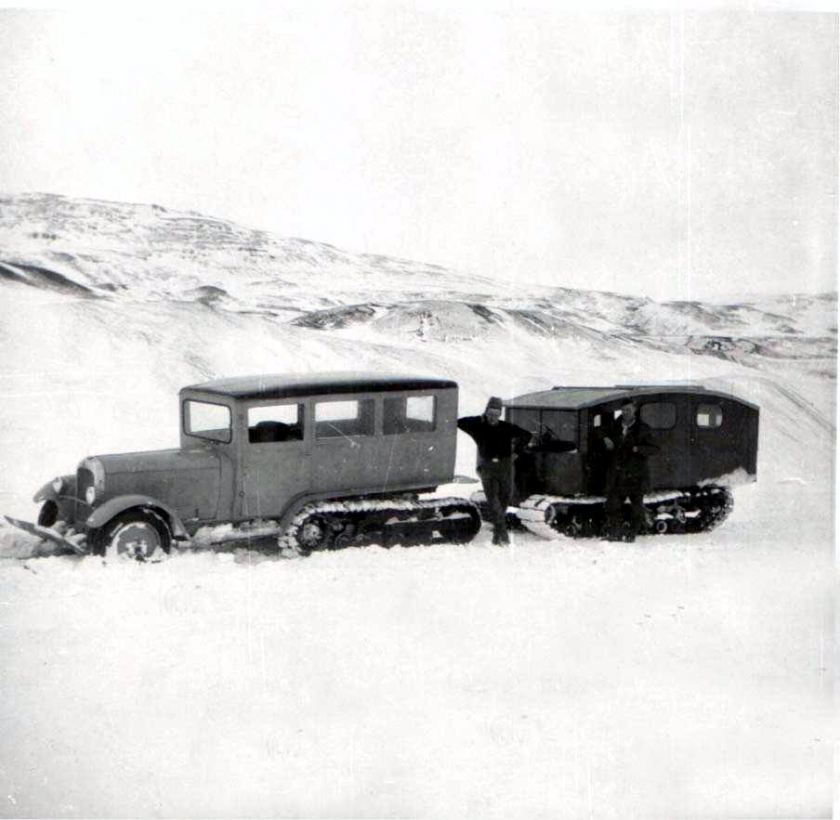

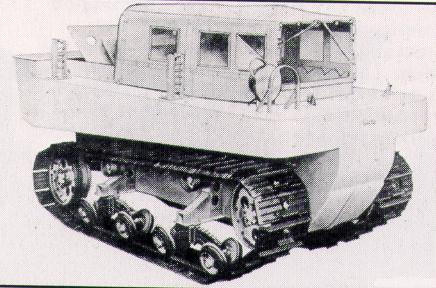

1917-russian-imperial-state-limousine-a-1916-packard-twin-6-touring-car-equipped-with-kegresse-track-1917

1917-packard-engine-6900cc

1917-packard-twin-six-2-25-convertible-coupe-von-holbrook

packard-twin-six-3-serie-modell-3-35-seitengesteuerter-v12-90-ps-2600-min-links/left-limousine-1920-rechts/right-brougham-1918

1919-packard-albright

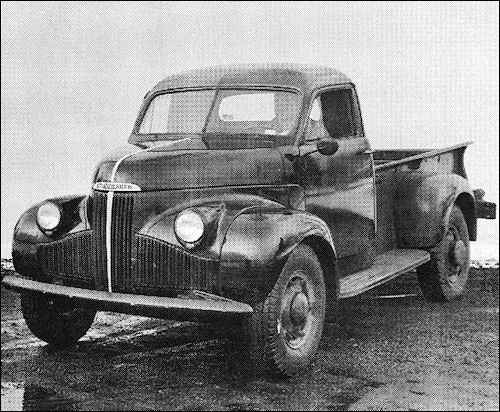

1919-packard-truck

1922-packard-phaeton

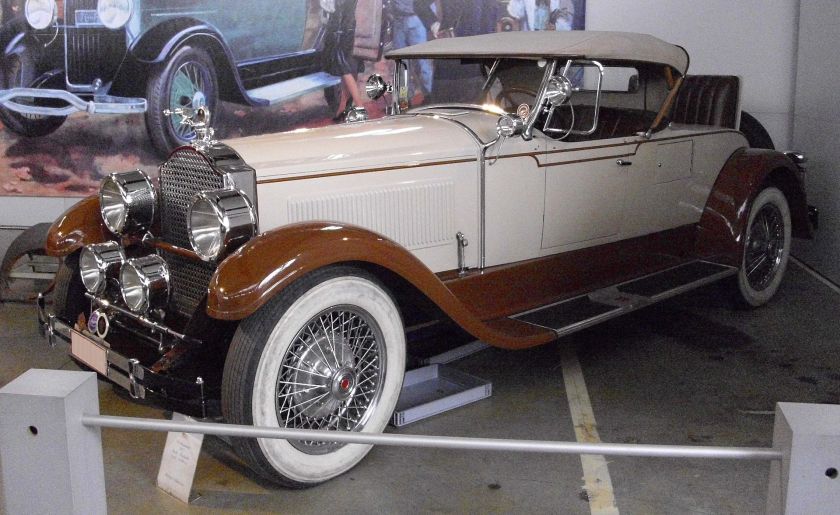

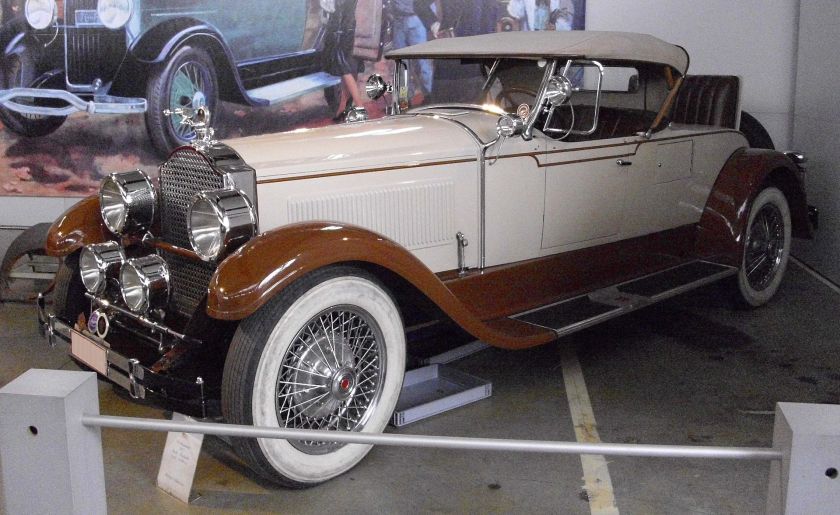

1922-packard-single-six-126-sportmodell-4 seats

1922-packard-single-six-modell-126-2-pass-runabout

1923-packard-single-six-226-touring

1924-packard-single-eight-143-town-car-by-fleetwood.

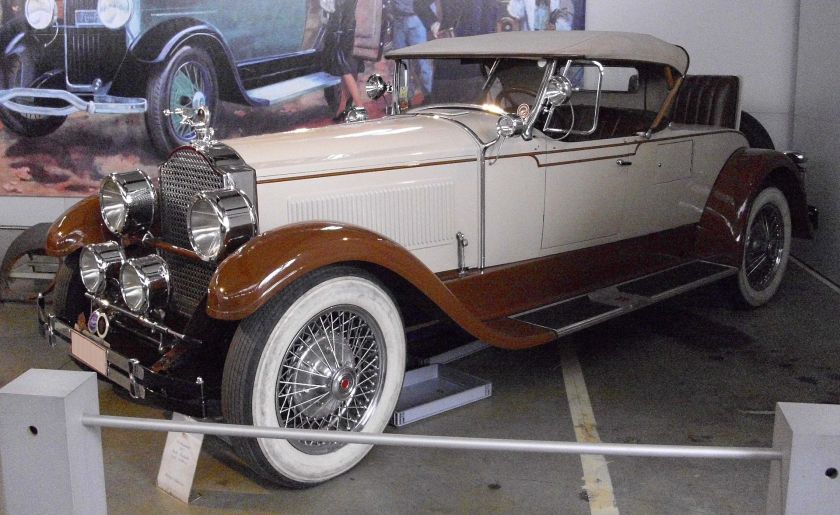

1926-packard-236

1926-packard-eight-modell-243-7-pass-touring

1927-packard-343-dual-windshield-phaeton

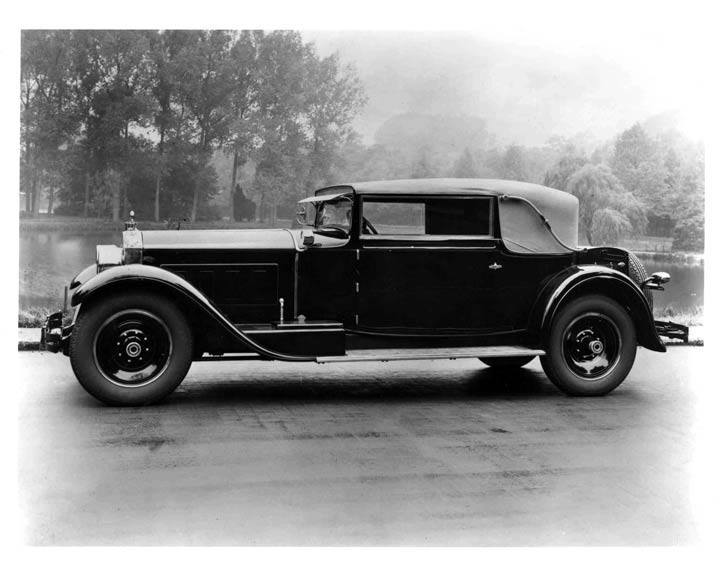

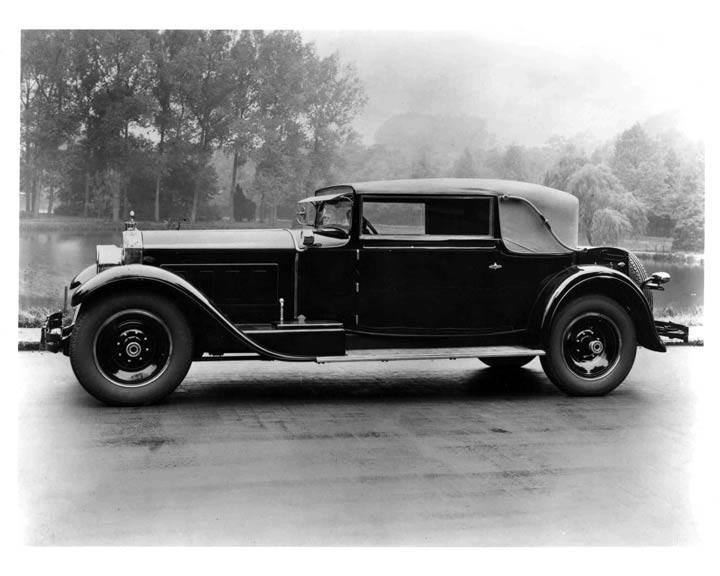

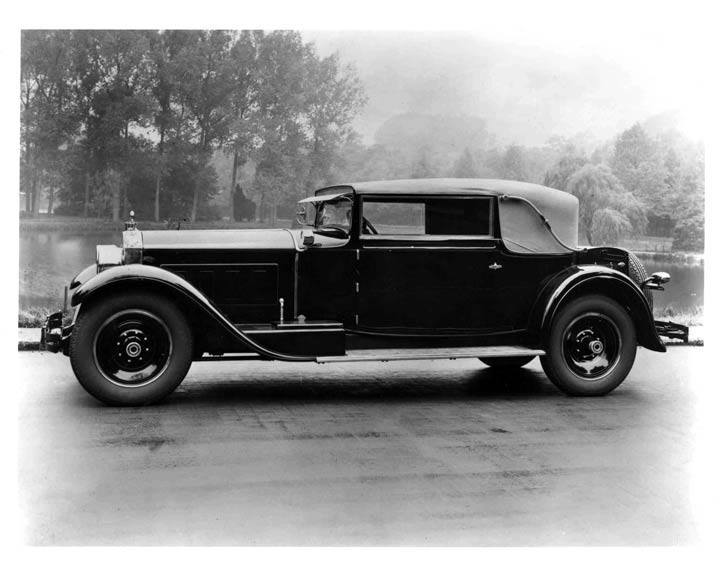

1927-packard-eight-modell-343-convertible-sedan-von-murphy

1927-packard-fourth-series-six-model-426-runabout-roadster

1927-packard-magazine-ad

1928-packard-526-convertable-coupe

1928-packard

1928-packard

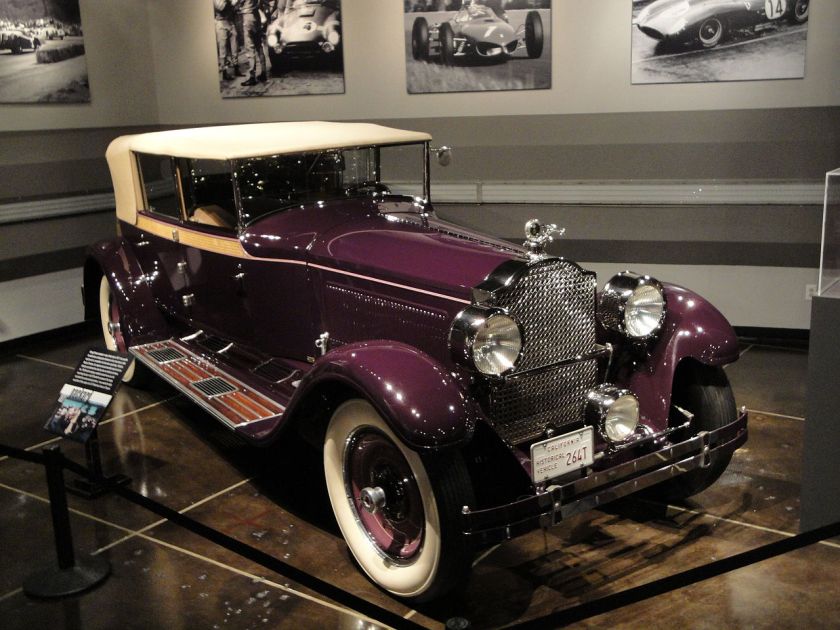

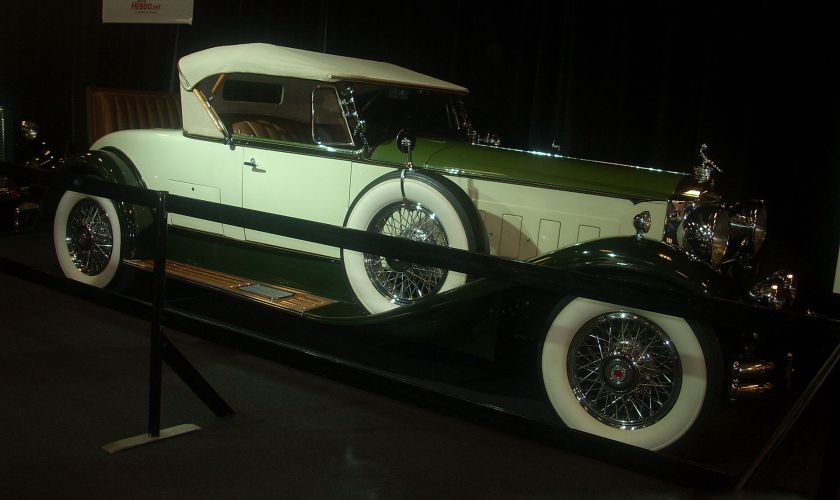

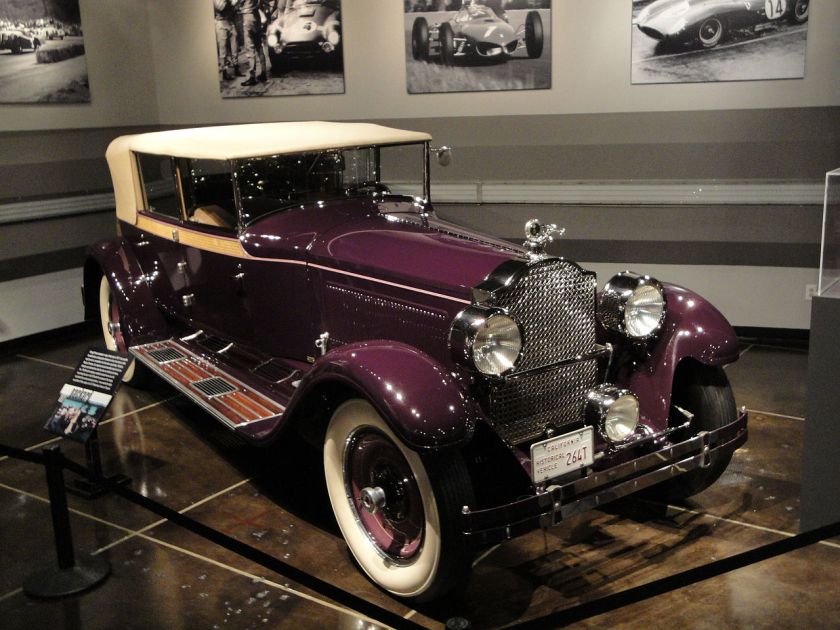

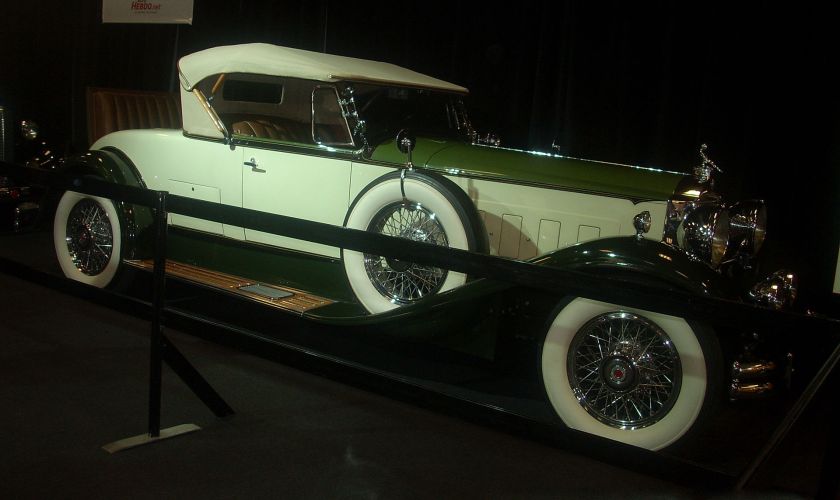

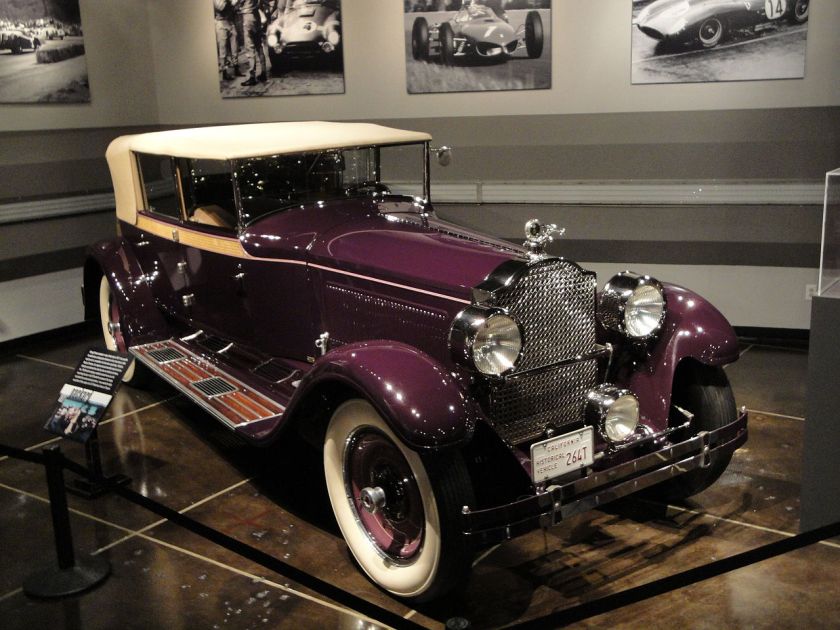

1929-packard-640-custom-eight

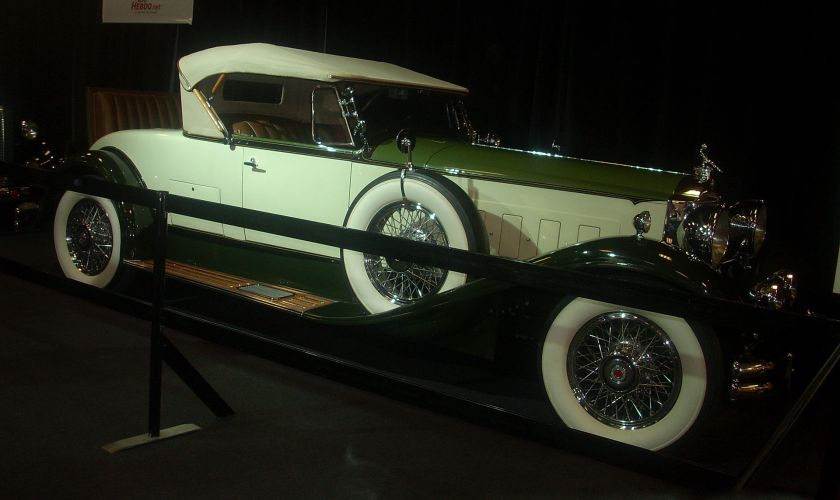

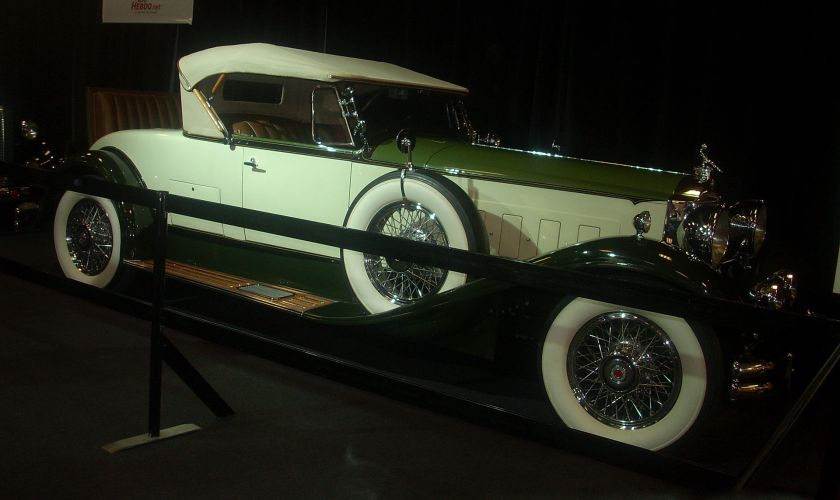

1929-packard-640-custom-eight-roadster

1929-packard-custom-eight-640-4-door-convertible-sedan-karosserie-von-larkins-san-francisco

1929-packard-m640-wrecker

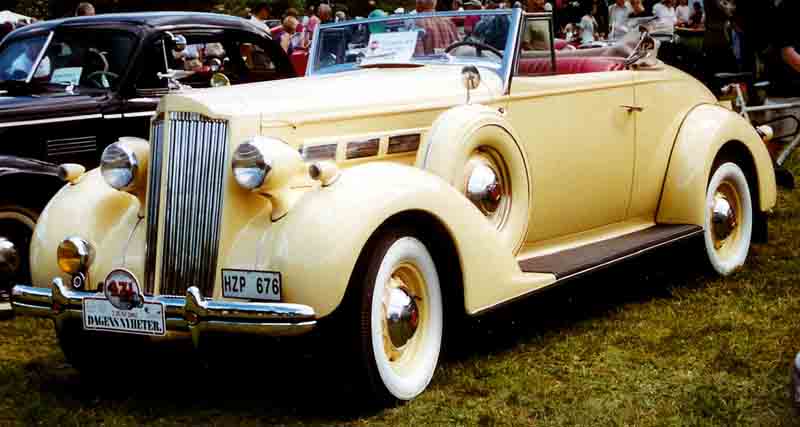

1930-packard-734-boattail-speedster

1930-packard-custom-eight-modell-740-coupé-roadster

1930-packard-standard-eight-733-coupé

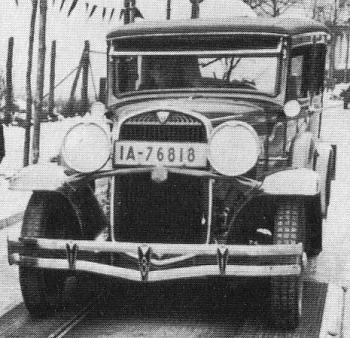

1930s-packard-eight-hyrbilar-under-tidigt-1930-tal-i-diplomatstaden-stockholm

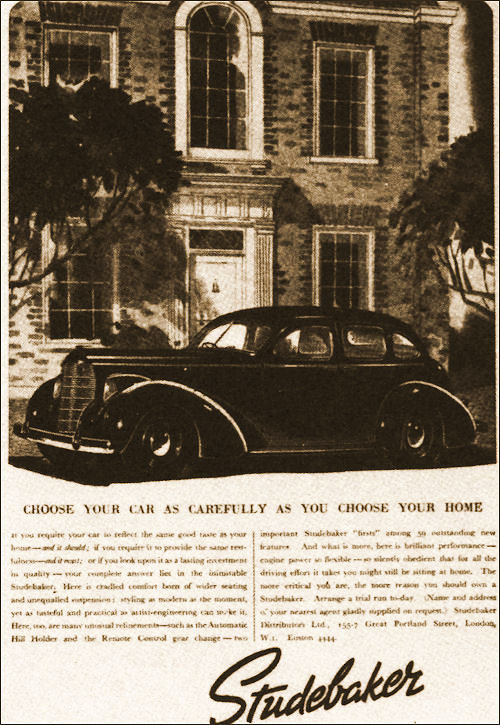

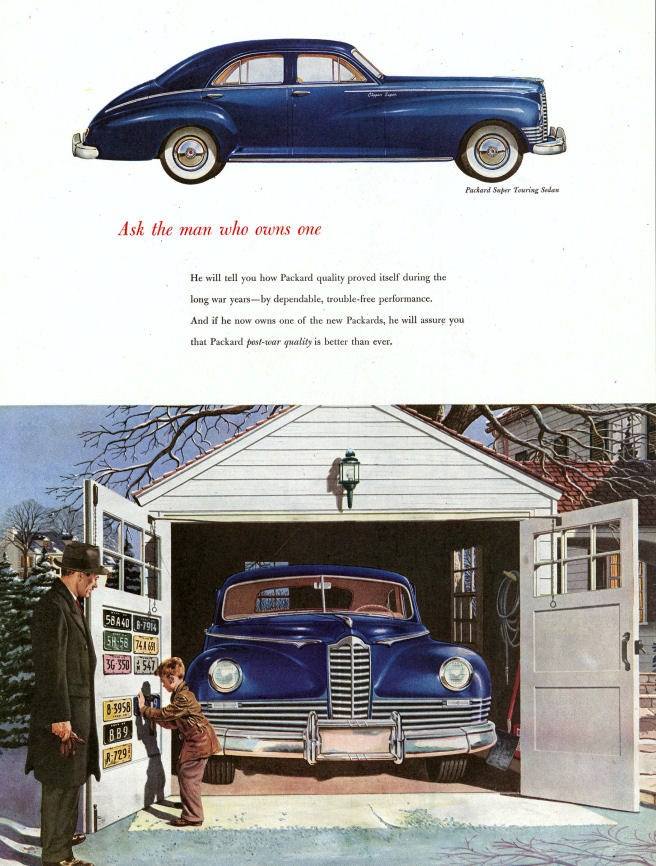

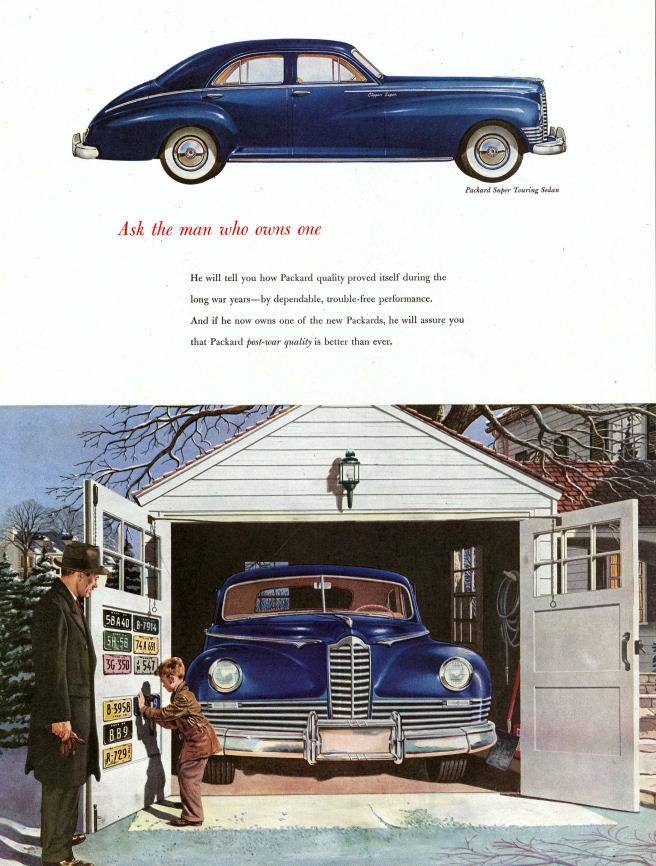

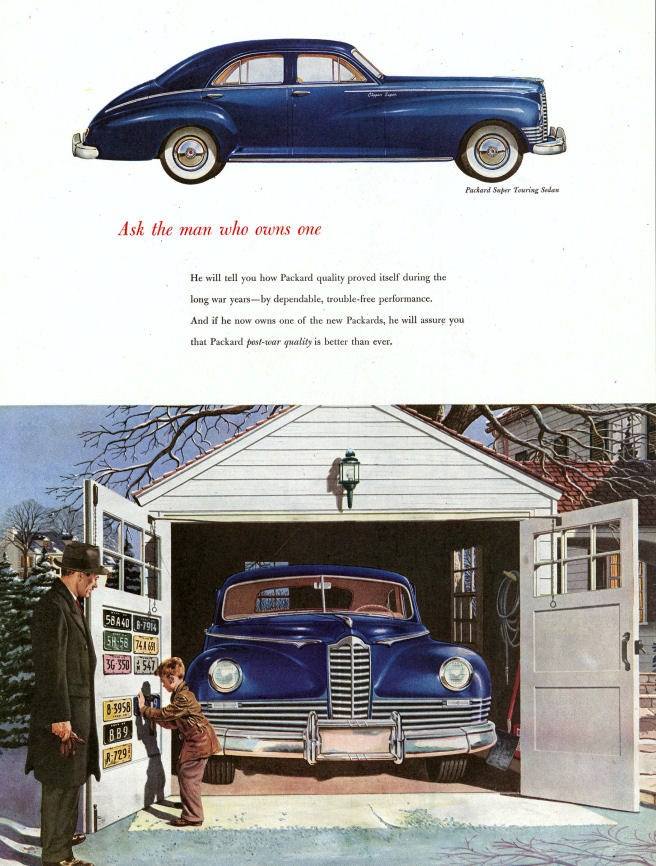

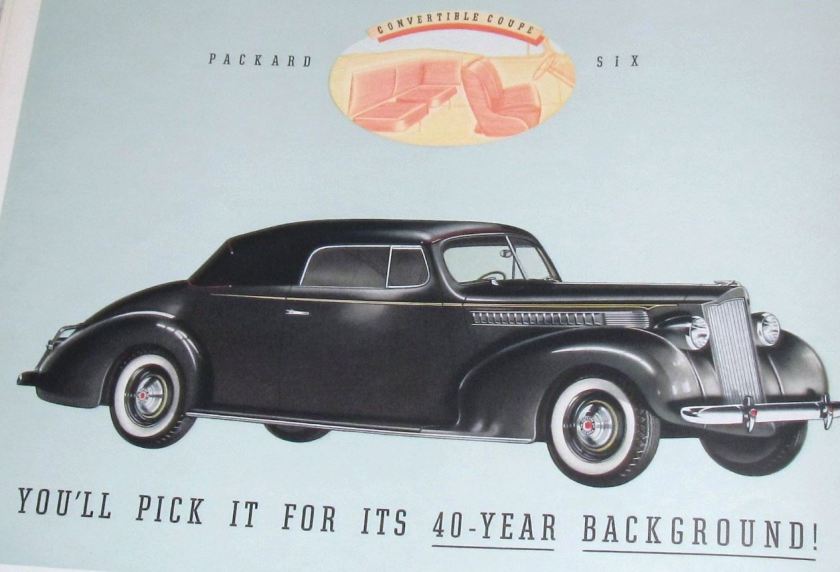

From this beginning, through and beyond the 1930s, Packard-built vehicles were perceived as highly competitive among high-priced luxury American automobiles. The company was commonly referred to as being one of the “Three P’s” of American motordom royalty, along with Pierce-Arrow of Buffalo, New York and Peerless of Cleveland, Ohio. For most of its history, Packard was guided by its President and General Manager James Alvan Macauley, who also served as President of the National Automobile Manufacturers Association. Inducted into the Automobile Hall of Fame, Macauley made Packard the number one designer and producer of luxury automobiles in the United States. The marque was also highly competitive abroad, with markets in sixty-one countries. Gross income for the company was $21,889,000 in 1928. Macauley was also responsible for the iconic Packard slogan, “Ask the Man Who Owns One.”

In the 1920s, Packard exported more cars than any other in its price class, and in 1930, sold almost twice as many abroad as any other marque priced over US$2000. In 1931, ten Packards were owned by Japan’s Royal Family. Between 1924 and 1930, Packard was also the top-selling luxury brand.

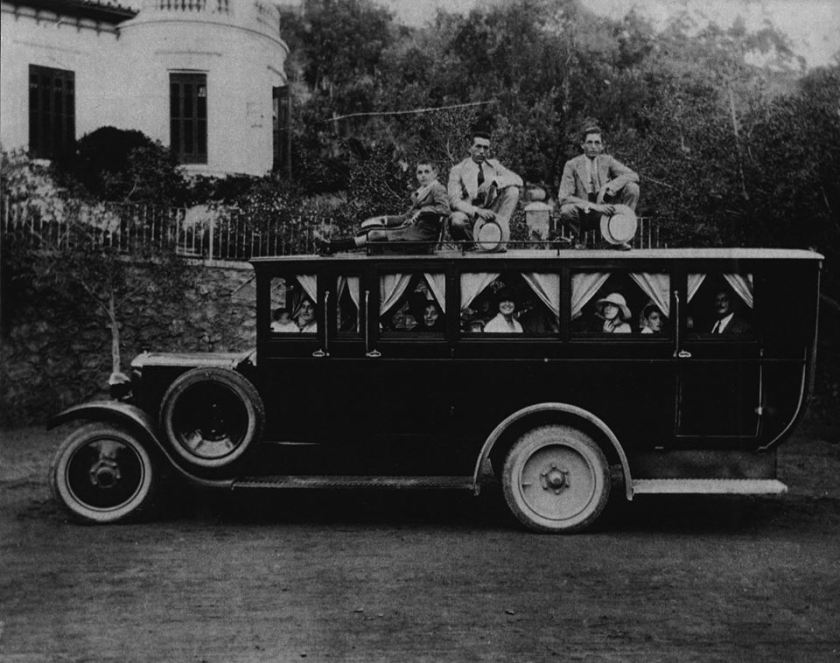

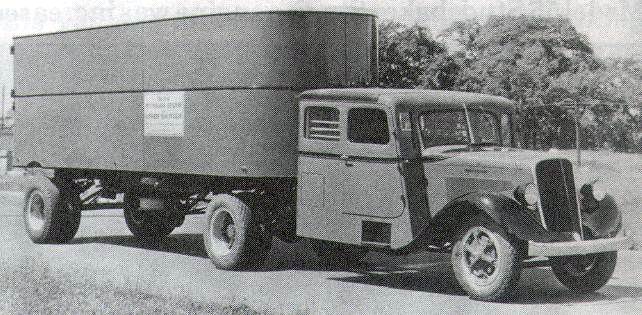

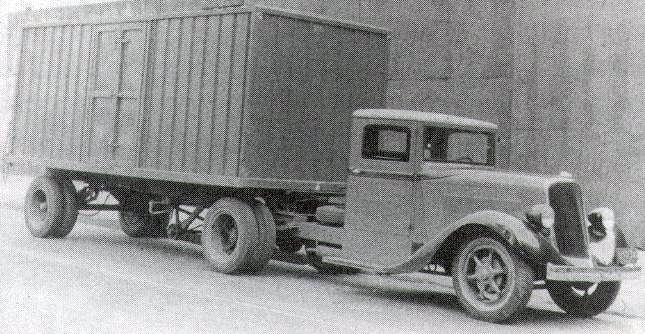

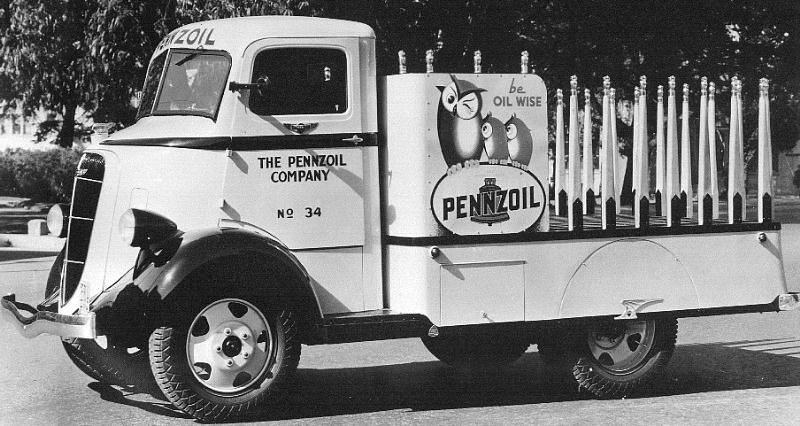

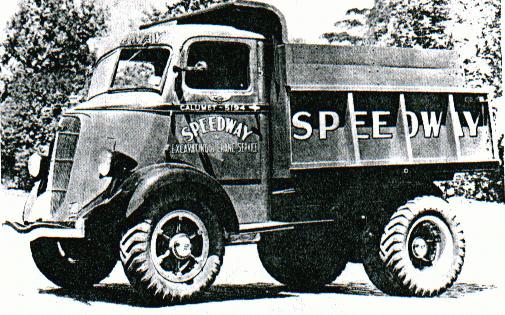

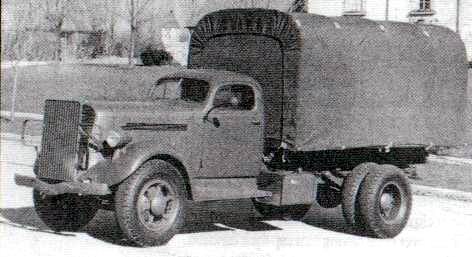

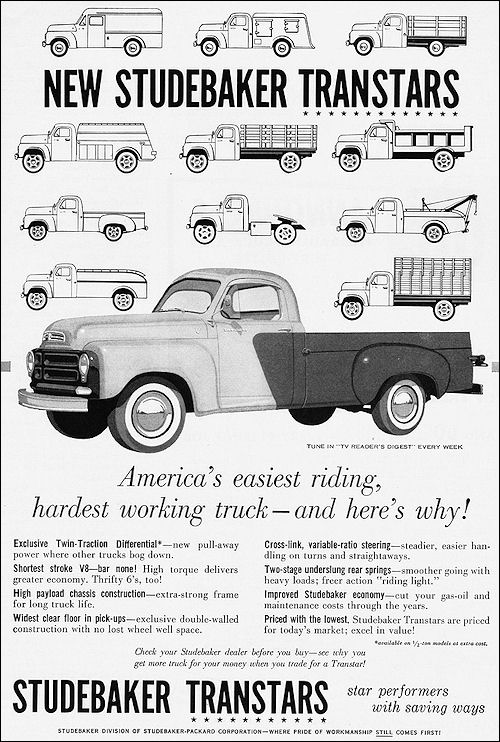

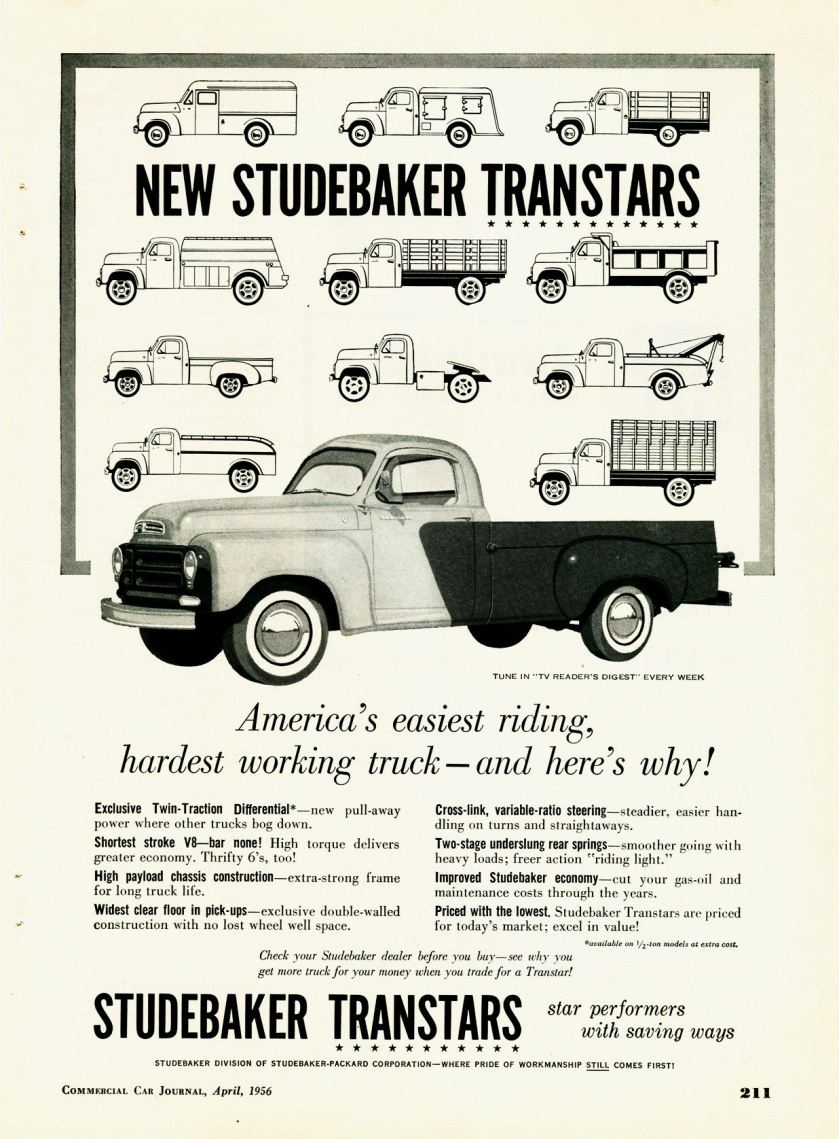

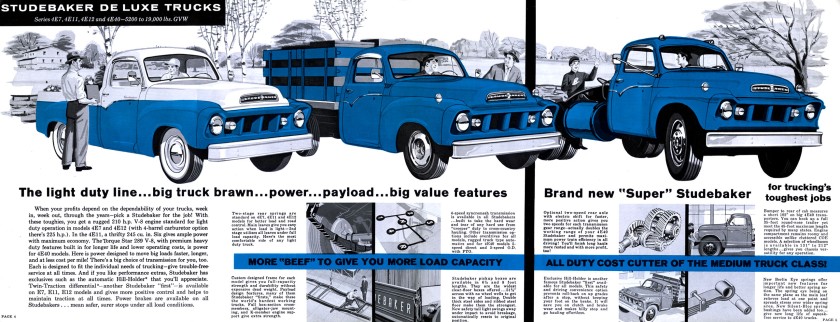

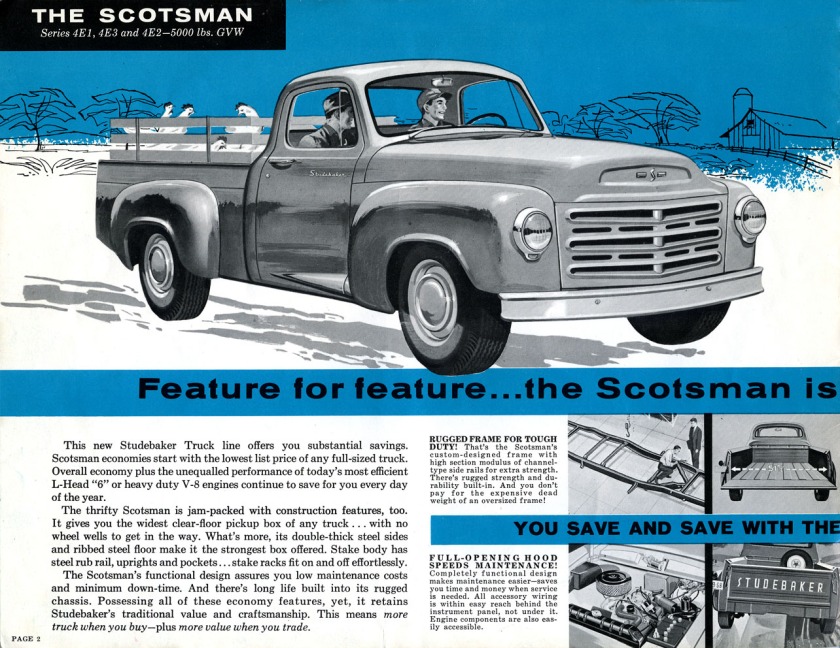

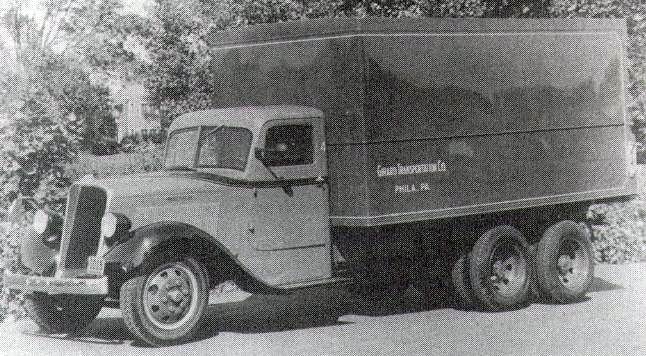

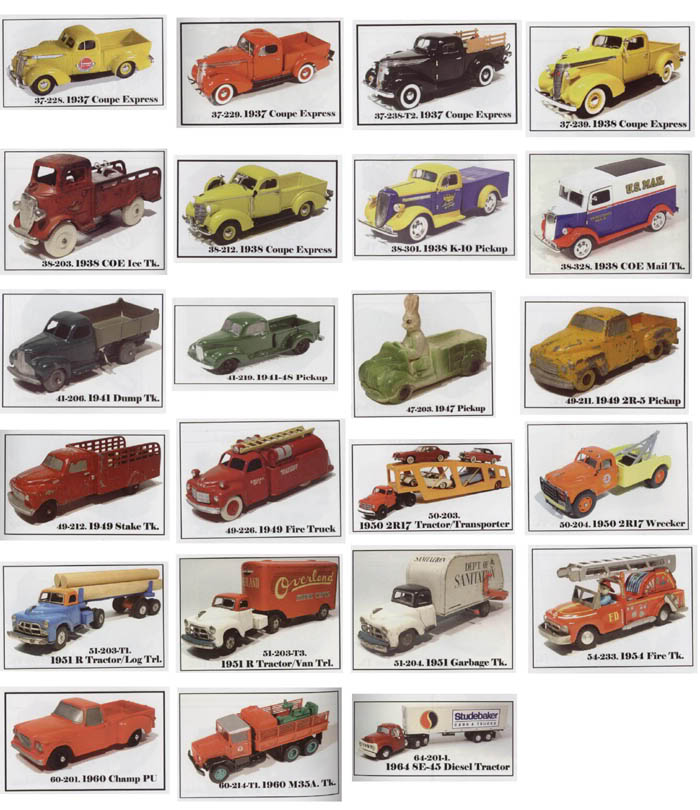

In addition to excellent luxury cars, Packard built trucks as well. A Packard truck carrying a three-ton load, drove from New York City to San Francisco between 8 July and 24 August 1912. The same year, Packard had service depots in 104 cities.

The Packard Motor Corporation Building at Philadelphia, also designed by Albert Kahn, was built in 1910-1911. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

By 1931, Packards were also being produced in Canada.

1931–1936

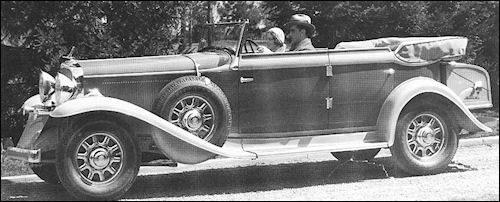

1930 Packard Deluxe Eight roadster

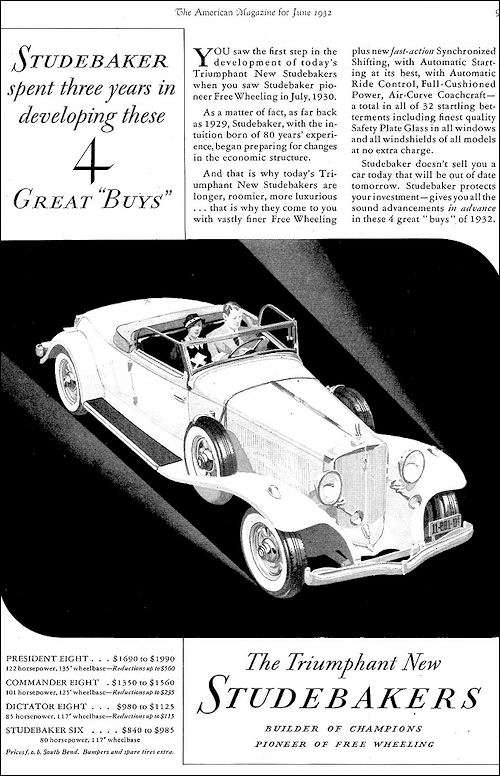

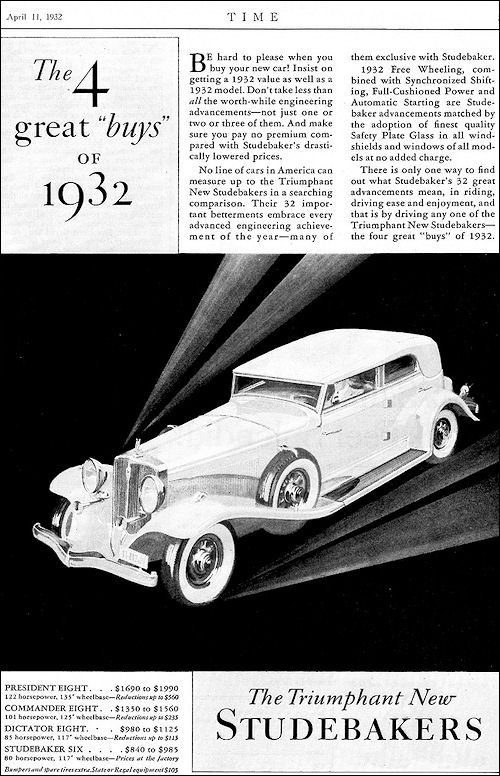

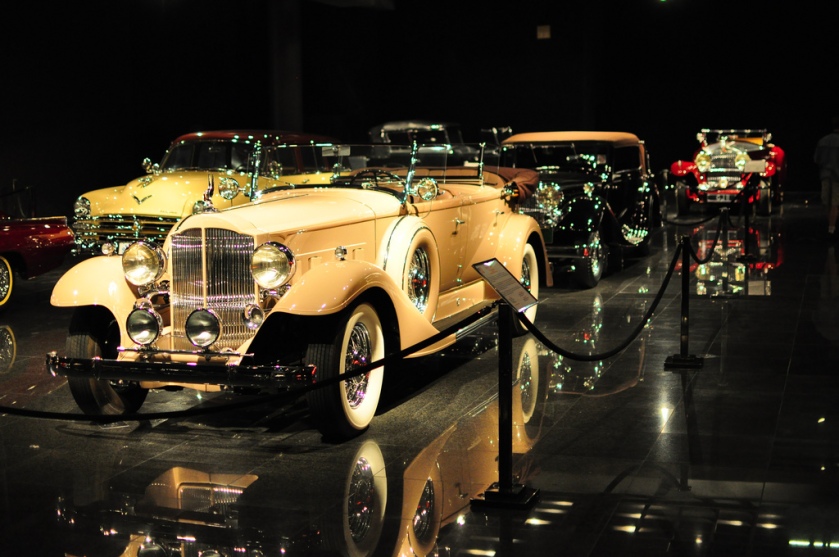

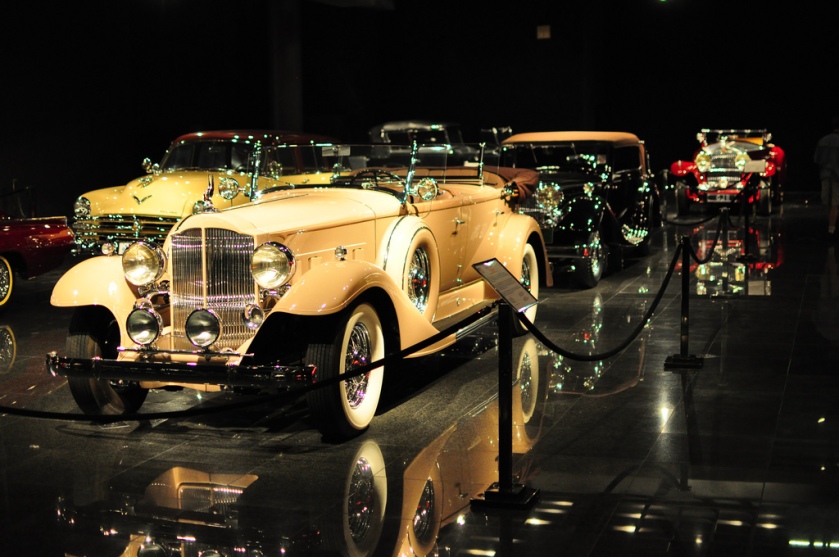

Entering the 1930s, Packard attempted to beat the stock market crash and subsequent Great Depression by manufacturing ever more opulent and expensive cars than it had prior to October 1929. While the Eight five-seater sedan had been the company’s top-seller for years, the Twin Six, designed by Vincent, was introduced for 1932, with prices starting at US$3,650 at the factory gate; in 1933, it would be renamed the Packard Twelve, a name it retained for the remainder of its run (through 1939). Also in 1931, Packard pioneered a system it called Ride Control, which made the hydraulic shock absorbers adjustable from within the car. For one year only, 1932, Packard fielded an upper-medium-priced car, the Light Eight, at a base price of $1,750 (about $27,933 in 2014), or $735 ($11,732) less than the standard Eight.

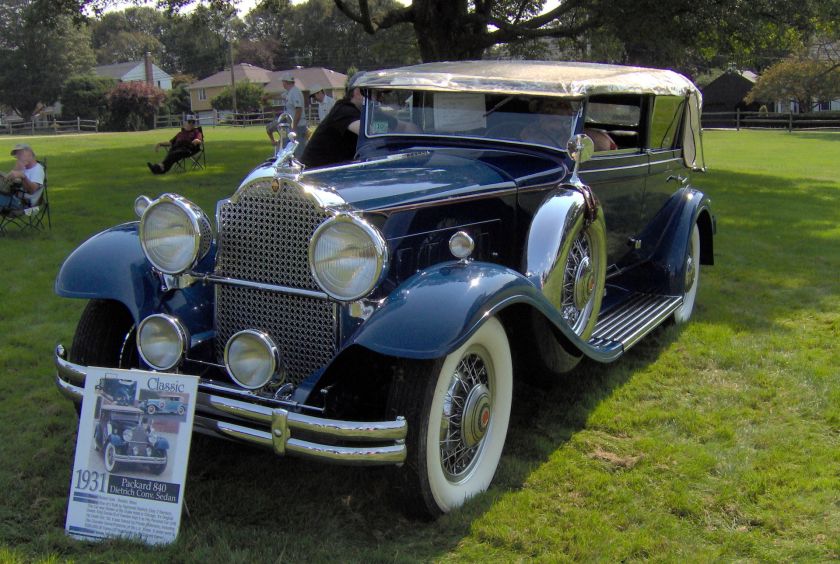

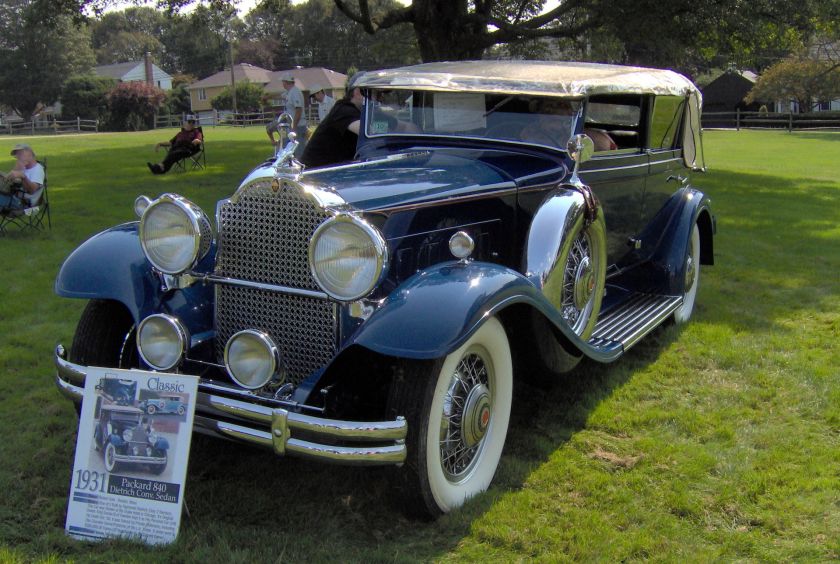

1931 Ninth Series model 840

1931-packard-845-convertible

1931-packard-individual-custom-eight-840-convertible-sedan-von-dietrich

1931-packard-standard-eight-833-2-4-passenger-coupe

As an independent automaker, Packard did not have the luxury of a larger corporate structure absorbing its losses, as Cadillac did with GM and Lincoln with Ford. However, Packard did have a better cash position than other independent luxury marques. Peerless ceased production in 1932, changing the Cleveland Ohio manufacturing plant from producing cars to brewing beer for Carling Black Label Beer. By 1938, Franklin, Marmon, Ruxton,Stearns-Knight, Stutz, Duesenberg, and Pierce-Arrow had all closed.

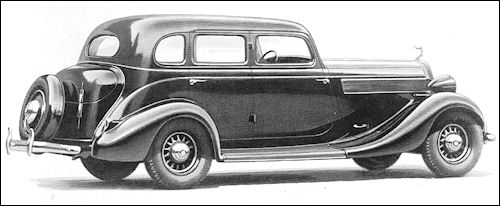

1932 Ninth Series De Luxe Eight model 904 sedan-limousine

1932-packard-light-eight-900-type-553-sedan

1932-st charles-packard-1

1933-packard-12-cylinder-touring-sedan-convertible

1933-packard-series-1105-convertible-coupe©chad younglove

1933-packard-twelve-individual-custom-twelve-modell-1005-sport-phaeton-von-dietrich

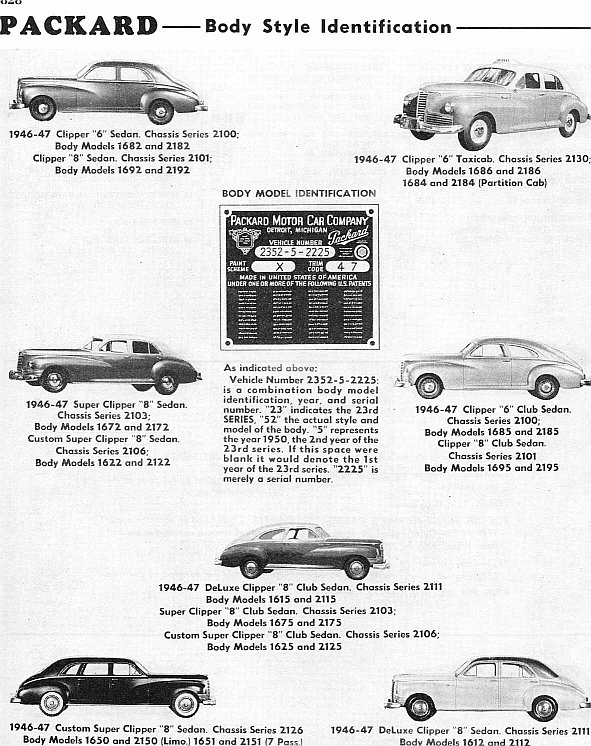

Packard also had one other advantage that some other luxury automakers did not: a single production line. By maintaining a single line and interchangeability between models, Packard was able to keep its costs down. Packard did not change cars as often as other manufacturers did at the time. Rather than introducing new models annually, Packard began using its own “Series” formula for differentiating its model changeovers in 1923. New model series did not debut on a strictly annual basis, with some series lasting nearly two years, and others lasting as short a time as seven months. In the long run, though, Packard averaged approximately one new series per year. By 1930, Packard automobiles were considered part of its Seventh Series. By 1942, Packard was in its Twentieth Series. The “Thirteenth Series” was omitted.

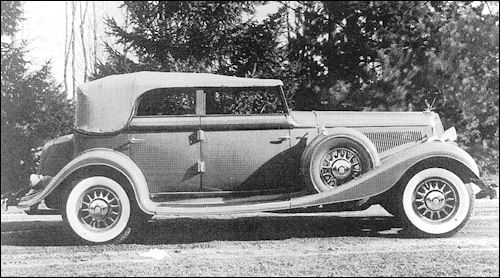

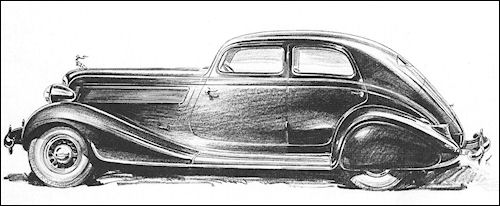

1934 Eleventh Series Eight model 1101 convertible sedan

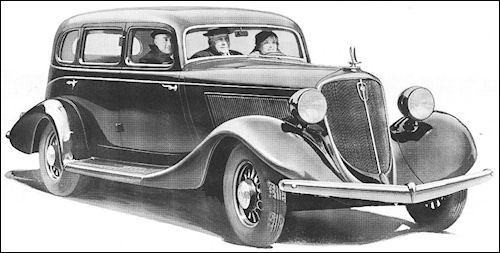

1934-packard-straight-eight-11th-series-sedan

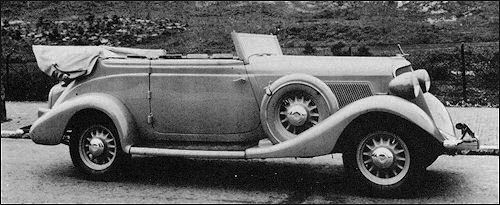

1934-packard-super-eight-1104-roadster-convertible

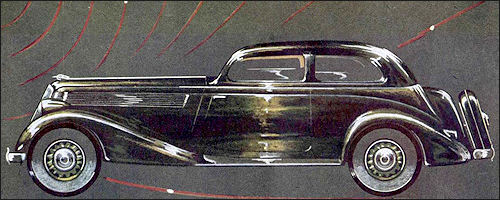

1934-packard-twelve-model-1106-sport-coupe-by-le baron

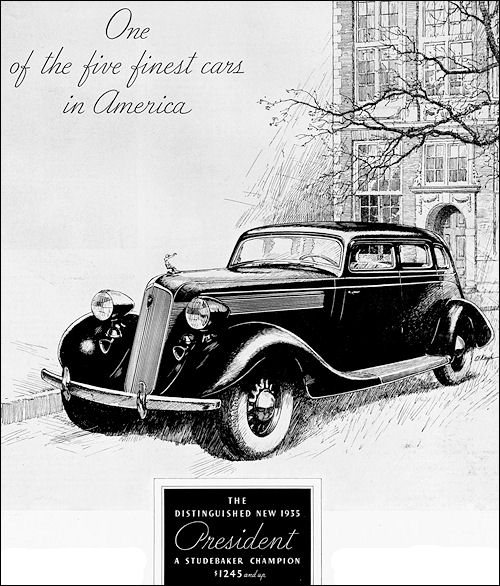

1935-packard-eight-model-1200-5-passenger-sedan-style-803-packards-preisgunstigstes(cheapest)-senior-modell

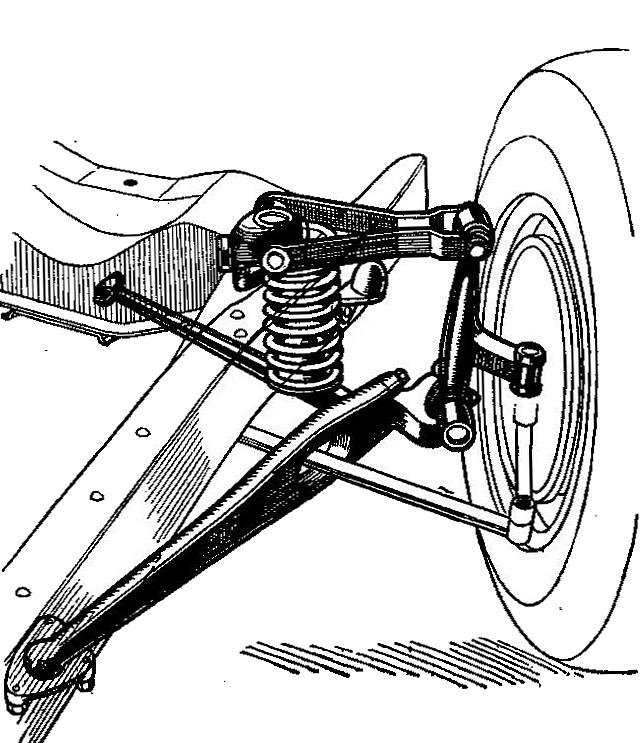

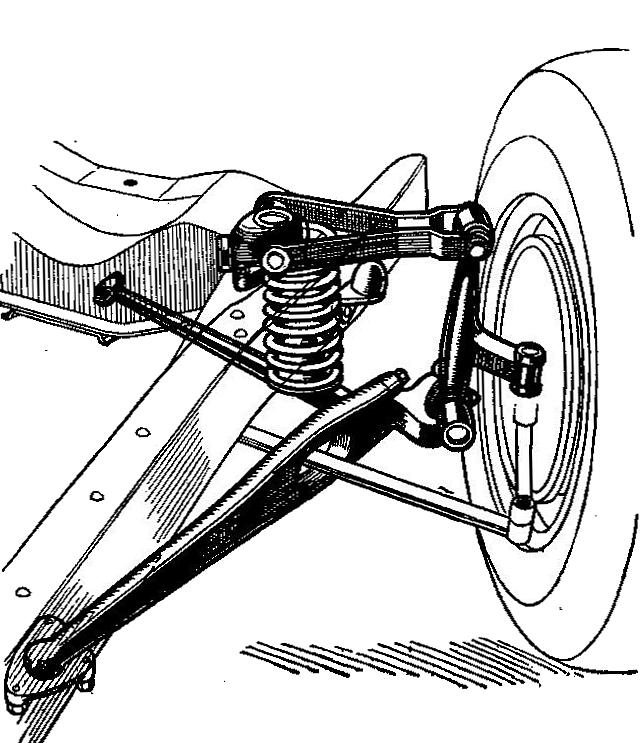

1935-packard-wishbone-front-suspension-autocar-handbook-13th-ed

1935-packard

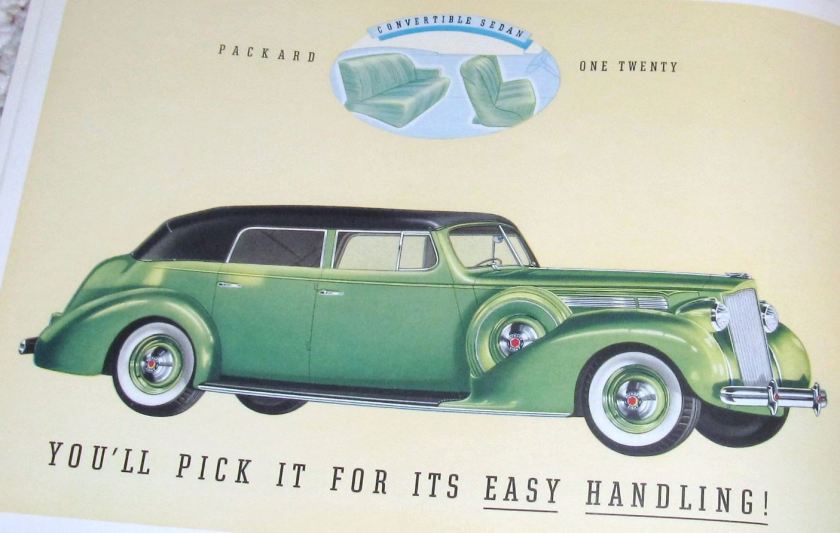

1936-packard-one-twenty-club-sedan-model-120-b-style-996

1936-packard-twelve-v12-modell-1406-convertible-victoria

1936-packard-v-12-convertible-sedan-by-dietrich

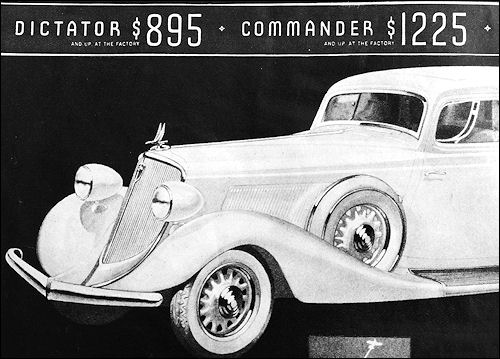

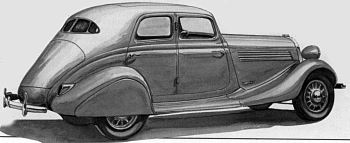

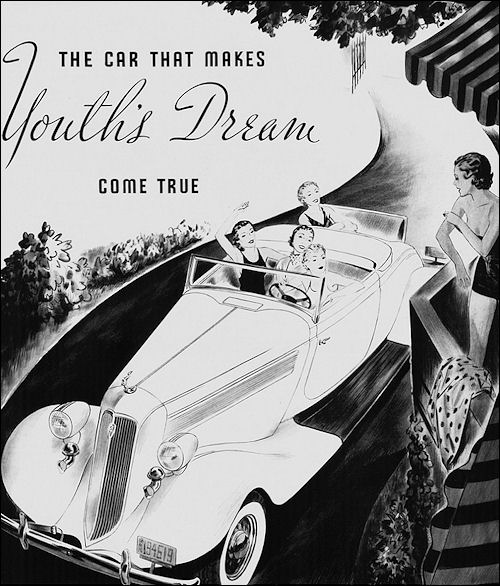

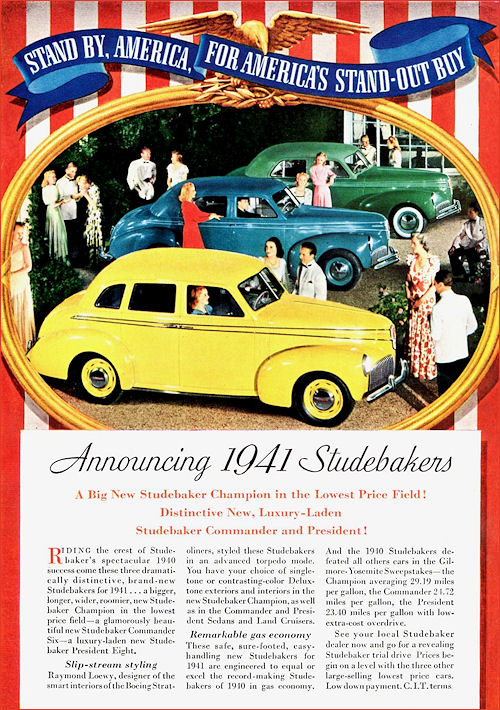

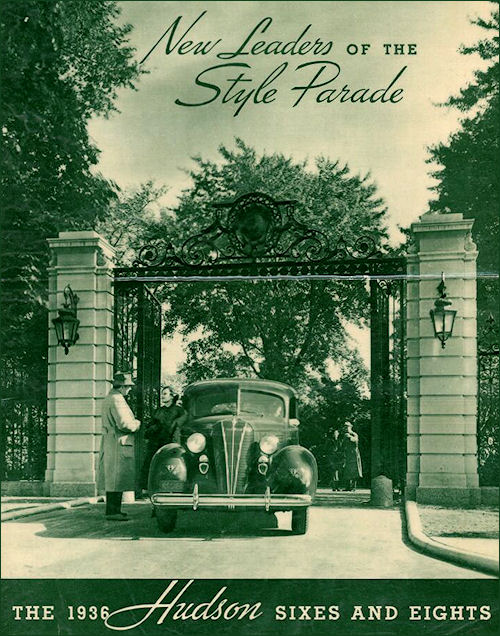

To address the Depression, Packard started producing more affordable cars in the medium-price range. In 1935, the company introduced its first sub-$1,000 car, the 120. Sales more than tripled that year and doubled again in 1936. In order to produce the 120, Packard built and equipped an entirely separate factory. By 1936, Packard’s labor force was divided nearly evenly between the high-priced “Senior” lines (Twelve, Super Eight, and Eight) and the medium-priced “Junior” models, although more than ten times more Juniors were produced than Seniors. This was because the 120 models were built using thoroughly modern mass production techniques, while the Senior Packards used a great deal more hand labor and traditional craftsmanship. Although Packard almost certainly could not have survived the Depression without the highly successful Junior models, they did have the effect of diminishing the Senior models’ exclusive image among those few who could still afford an expensive luxury car. The 120 models were more modern in basic design than the Senior models; for example, the 1935 Packard 120 featured independent front suspension and hydraulic brakes, features that would not appear on the Senior Packards until 1937.

1937–1941

1937-de-haan-packard

1937-packard-115c-coupe

1937-packard-super-eight-convertible-sedan

1937-packard-super-eight

1938-packard

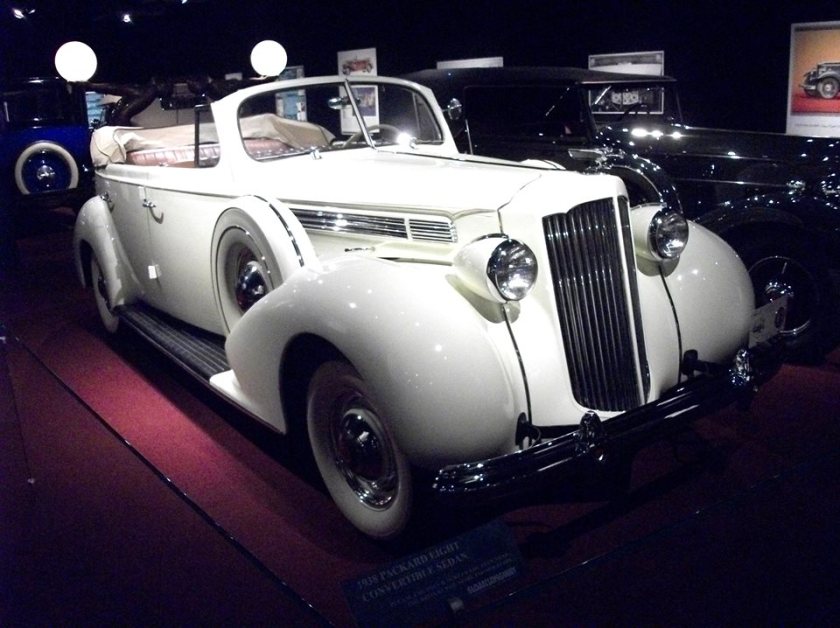

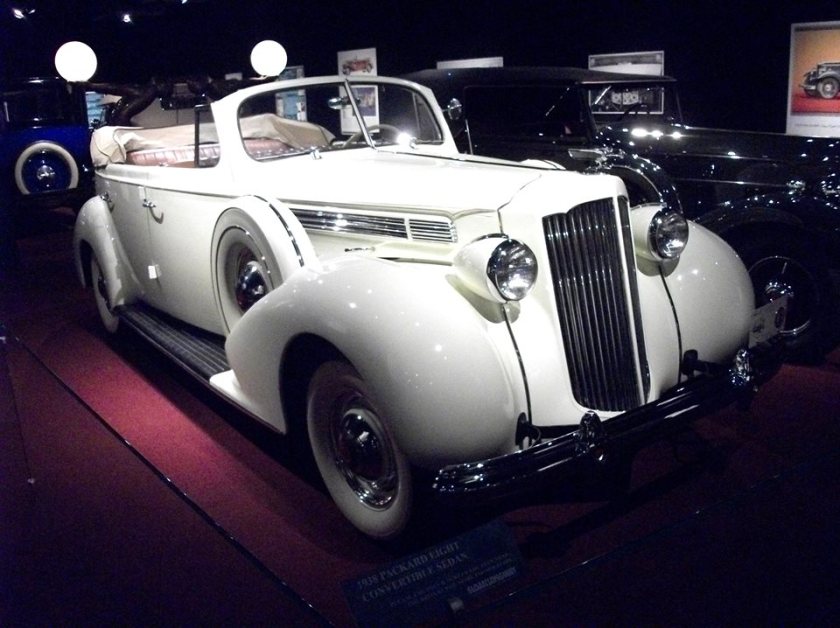

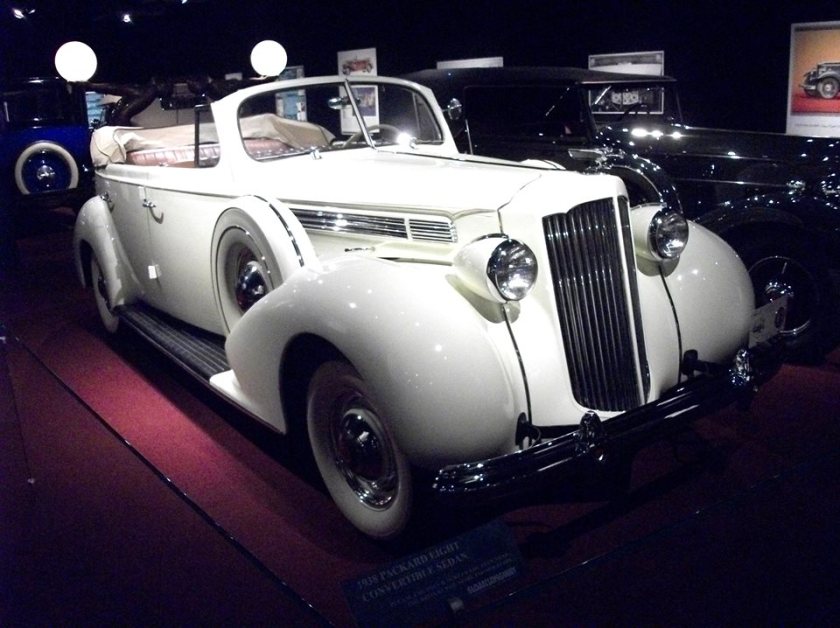

1938-packard-eight-convertible-sedan

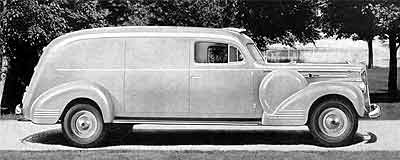

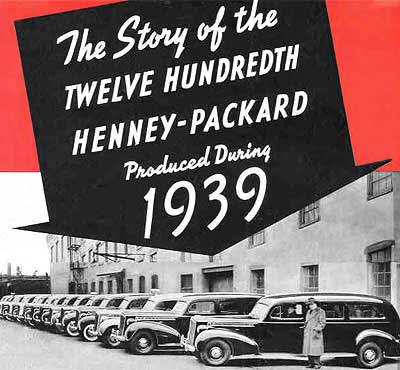

1938-packard-henney-stationwagen-12-person

1938-packard-six-model-1600-club-coupe

1938-packard-super-eight.

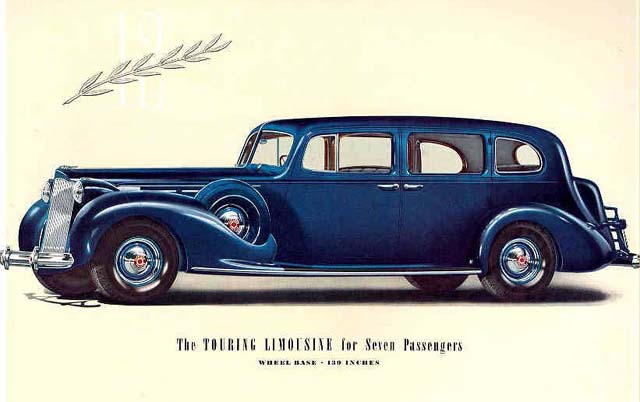

1938-packard-touring-limousine ad

1939-packard-one-twenty-business-coupe

1939 Packard Packard Twelve, 17th series

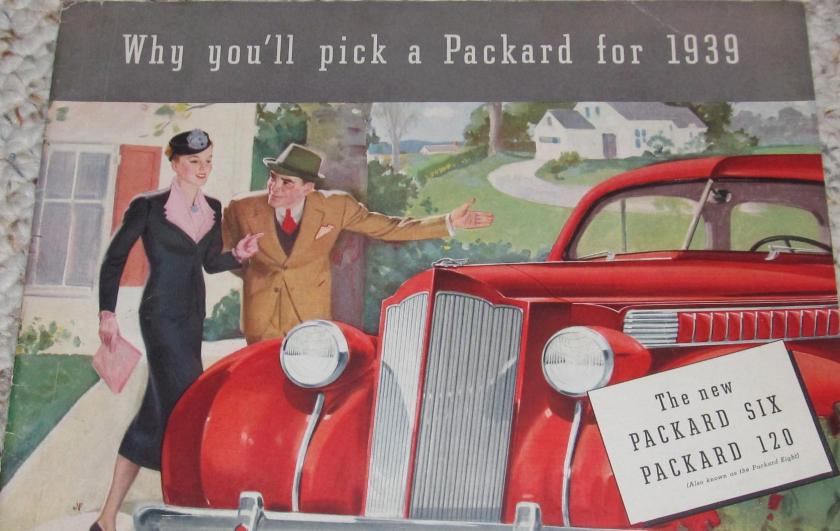

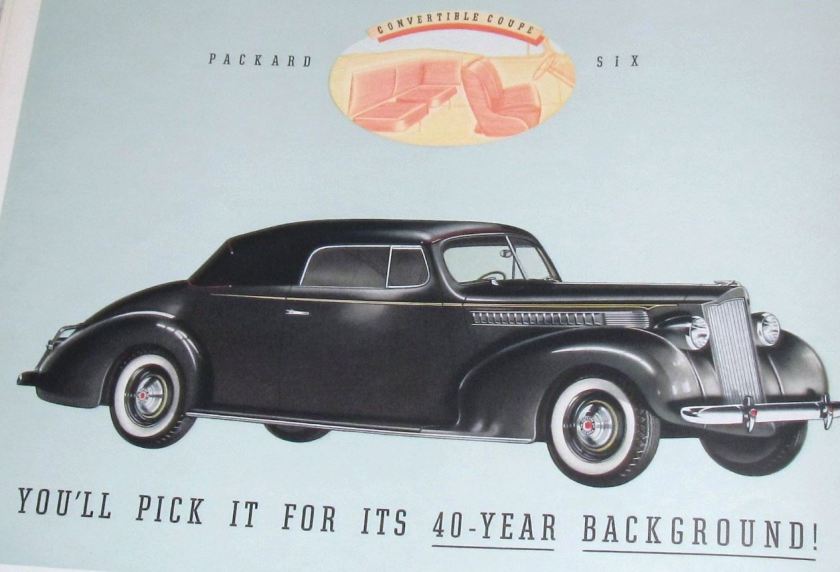

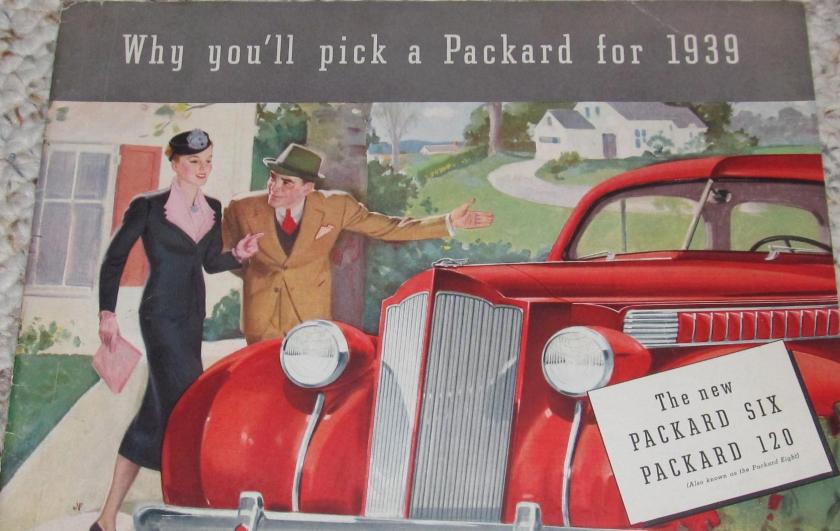

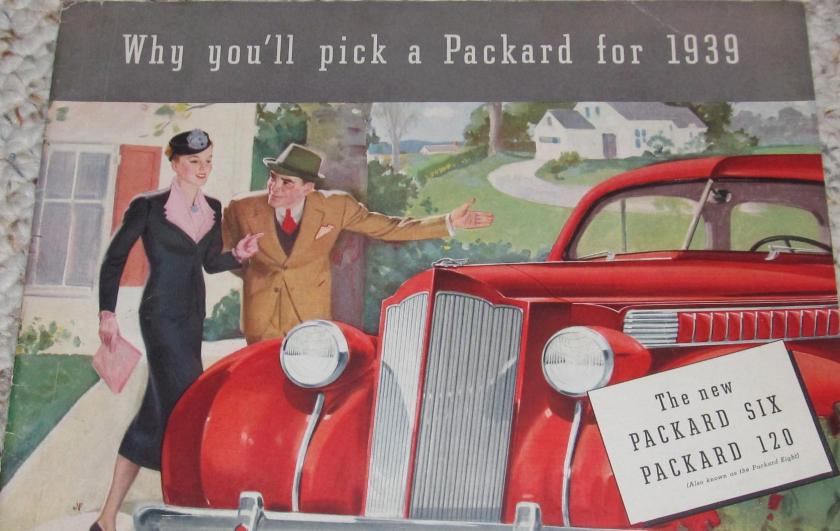

1939-packard-six-120 ad

1939-packard-super-eight-model-1705-touring-sedan

1939-packard-super-eight-model-1705-touring-sedan

1939-packard-taxi

1939-packard-twelve-17-serie-von-us-präsident-franklin-delano-roosevelt

1939-packard-twelve-brunn-cabriolet

1939-packard-twelve-formal-sedan

1939-packard

1940-packard-120-modell-1801-convertible-victoria-von-darrin

1940-packard-180-custom-super-8-1806-parisienne-victoria-by-darrin

1940-packard-custom

1940-packard-one-twenty-coupé-18-serie-in-frage-kommen-1801-1398-business-coupe-1801-1395-club-coupe-oder-1801-1395de-deluxe-club-coupe

1940-packard

1940-packard

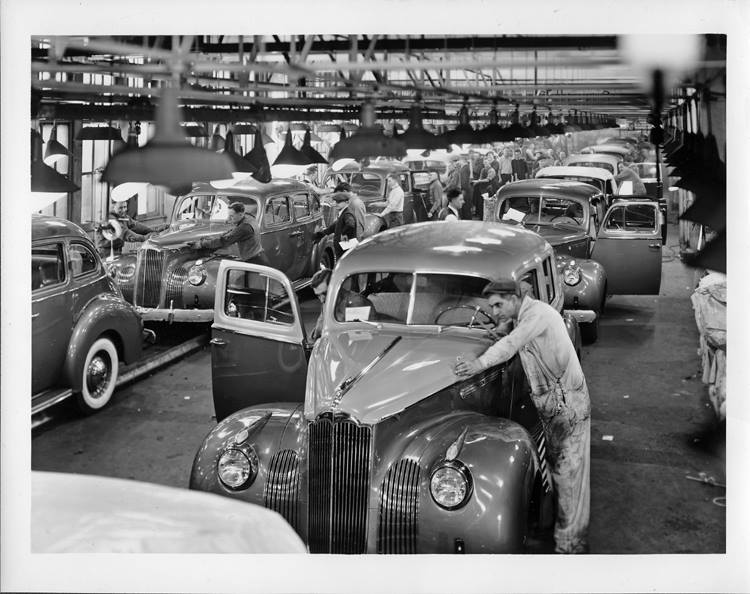

1941-la-linea-de-montage-de-packard-modelos-110-120-160-y-180

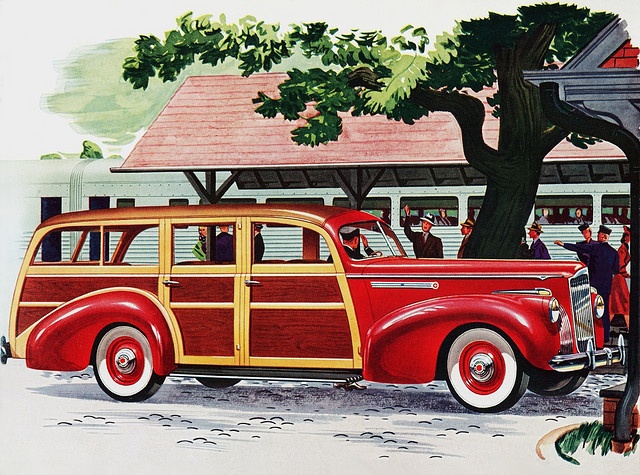

1941-packard-110-deluxe-woody-station-wagon

1941-packard-120-coupe

1941-packard-120-station-sedan-woody

1941-packard-160-super-8-1905-rollston-limousine

1941 Packard Custom Super Eight One-Eighty Formal sedan; 19th series, Model 1907

1941-packard-clipper-darrin-convertible-victoria

1941-packard-clipper-sedan

1941-packard-clipper-taxi.

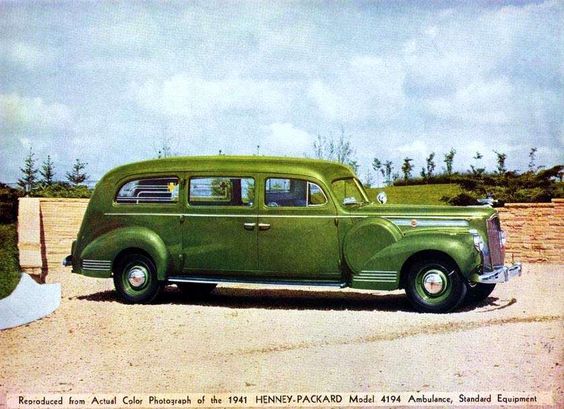

1941-packard-henney-limo-400

1941-packard-limousine-by-lebaron

1941-packard-model-120-convertible

1941-packard-one-eighty-formal-sedan

1941 Packard Station Wagon advertisement; either One-Ten Model 1900 or One-Twenty Model 1901

1941-packard-station-wagon-model-110

1941-packard-swan

1941-packard-henney-cc-bw-400 hearse

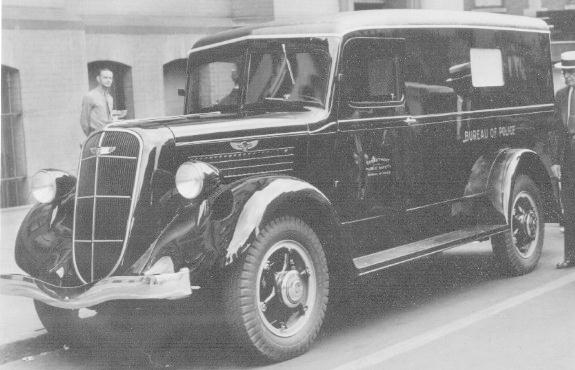

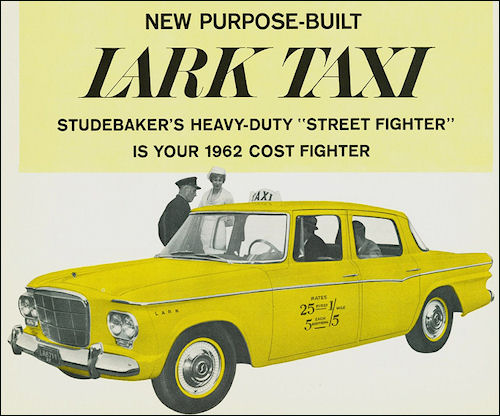

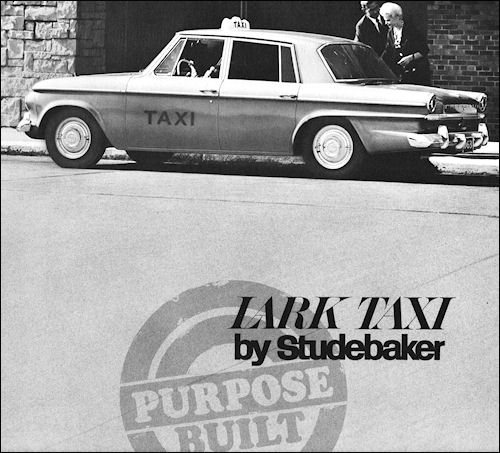

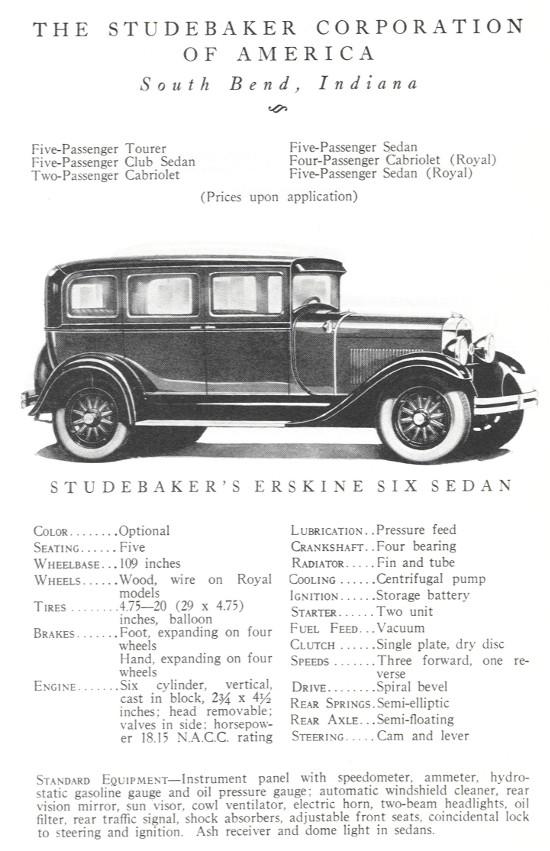

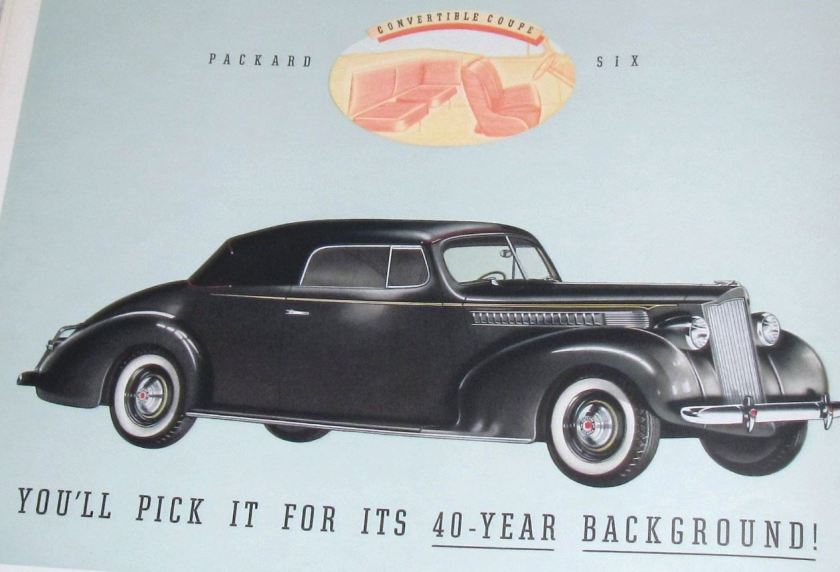

Packard was still the premier luxury automobile, even though the majority of cars being built were the 120 and Super Eight model ranges. Hoping to catch still more of the market, Packard decided to issue the Packard 115C in 1937, which was powered by Packard’s first six-cylinder engine since the Fifth Series cars in 1928. While the move to introduce the Six, priced at around $1200, was brilliant, for the car arrived just in time for the 1938 recession, it also tagged Packards as something less exclusive than they had been in the public’s mind, and in the long run hurt Packard’s reputation of building some of America’s finest luxury cars. The Six, redesignated 110 in 1940–41, continued for three years after the war, with many serving as taxicabs.

In 1939, Packard introduced Econo-Drive, a kind of overdrive, claimed able to reduce engine speed 27.8%; it could be engaged at any speed over 30 mph (48 km/h). The same year, the company introduced a fifth, transverse shock absorber and made column shift (known as Handishift) available on the 120 and Six.

1942–1945

1942-packard-20-serie-super-eight-one-sixty-limousine

1942-packard-clipper-160-millitary-staff-car.

1942-packard-six-115-convertible-coupc3a9-modell-2000

Russian copy of Packard the ZIS 110

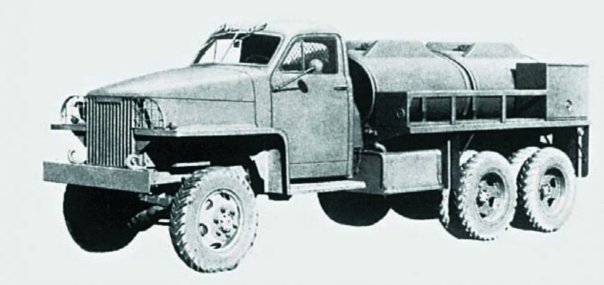

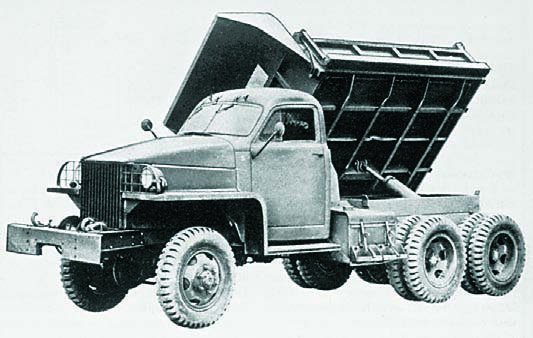

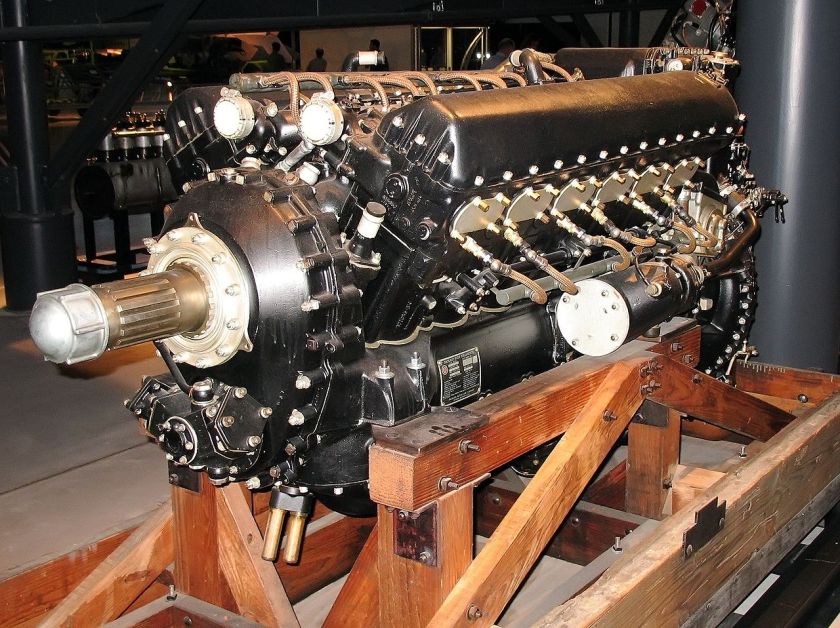

In 1942 the Packard Motor Car Company converted to 100% war production. During World War II, Packard again built airplane engines, licensing the Merlin engine from Rolls-Royce as the V-1650, which powered the famous P-51 Mustang fighter, ironically known as the “Cadillac of the Skies” by GIs in WWII. Packard also built 1350-, 1400-, and 1500 hp V-12 marine engines for American PT boats (each boat used three) and some of Britain’s patrol boats. Packard ranked 18th among United States corporations in the value of wartime production contracts.

By the end of the war in Europe, Packard Motor Car Company had produced over 55,000 combat engines totaling 84,356,900 horsepower. Sales in 1944 were $455,118,600. By May 6, 1945 Packard had a backlog on war orders of $568,000,000.

1946–1956

1946-packard-clipper-super-sedan

1946-47-packard-clipper-super-touring-sedan-modell-2103

1946-47-packard

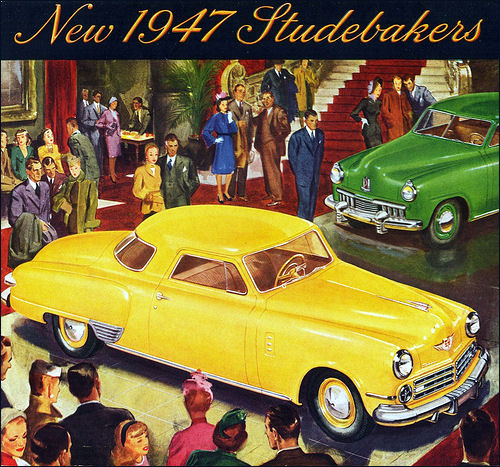

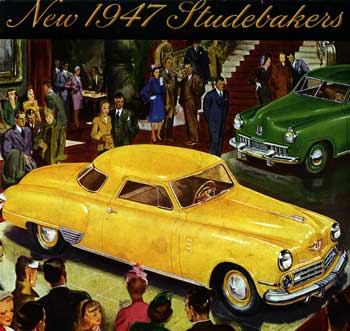

1947-packard-ad

1947-packard-clipper-2-door

1947-packard-clipper

1947-packard-clipper-custom-touring-sedan-modell-2106-1622-21

1947-packard-clipper-super-touring-sedan-modell-2103-1672-1946-oder-2103-2172-

1947-packard-clipper-eight

1947-packard-custom-super-clipper-club-sedan

1948-packard-2201-six-passenger-sedan-woodie-right

1948-packard-clipper-six.

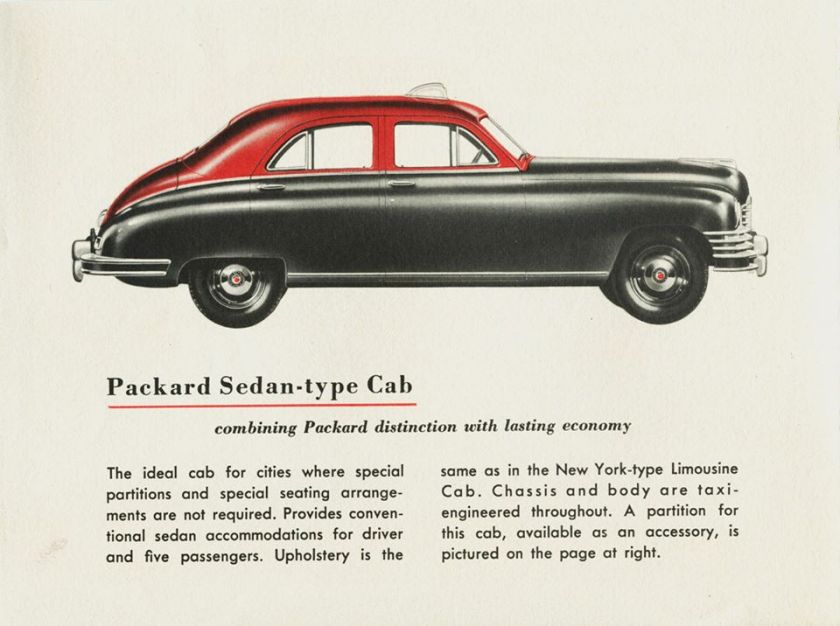

1948-packard-sedan-type-taxicab

1948-packard-station-sedan

1948-packard-super-eight-victoria-convertible-coupe

1948-packard-woody

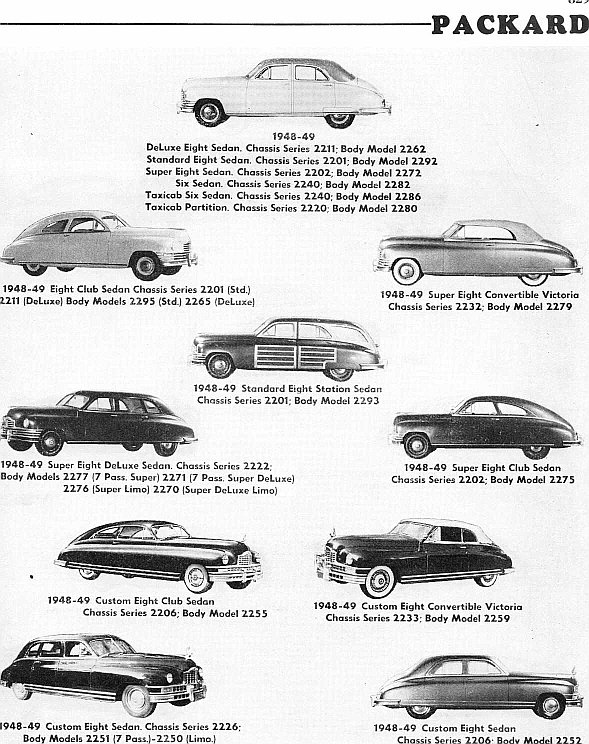

1948-49-packard

1949-packard-convertible-coupé

1949-packard-custom-eight-convertible-coupe

1949-packard-station-sedan

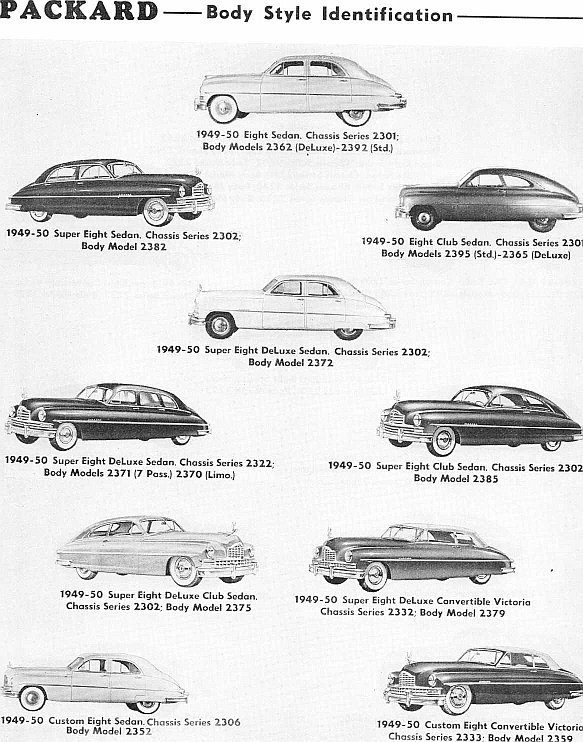

1949-50-packard

1950-packard-eight-4-door-sedan

1950-packard-eight-4-door-sedan

1950-packard-super-8-talla-hood-marque

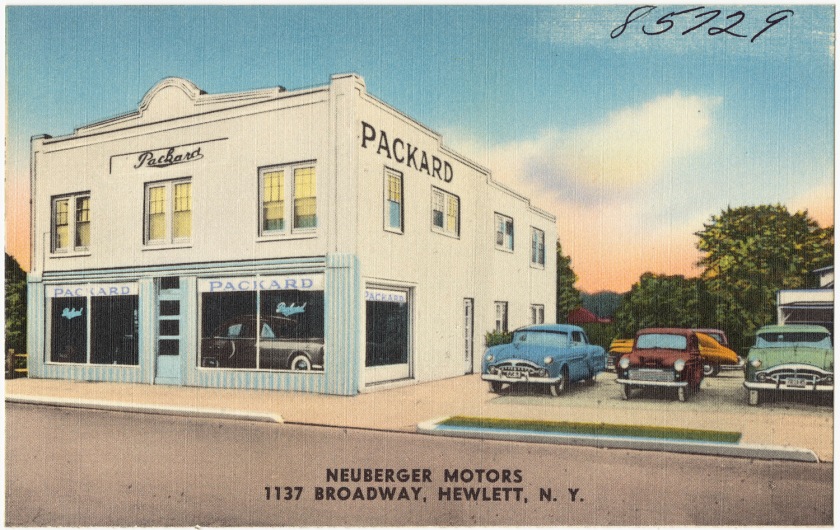

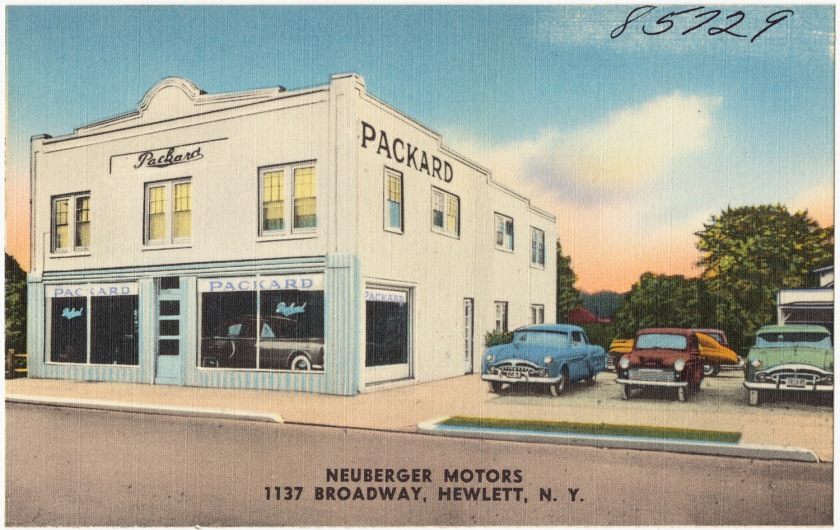

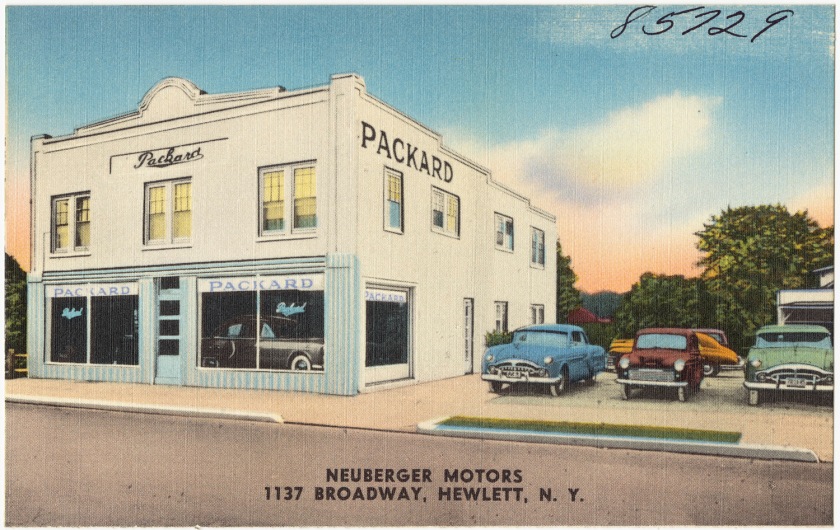

Packard dealer in New York State, ca. 1950-1955

1951-packard-200-2401-standard-sedan

1951-packard-200-club-sedan

1951-packard-200-touring-sedan-modell-2401-2492

1951-packard-250-convertible-modell-2401-2469

1951-packard-300-touring-sedan-model-2402e

1951-packard-clipper-darrin-convertible

1951-52-packard

1952-packard-200-touring-sedan

1952-packard-400-patrician-2406-sedan

1952-packard-balboa-400

1952-packard-carry-all

1952-packard-pan-american-show-car

1952-packard-parisian

1952-packard-patrician-400

1952-packard-special-speedster

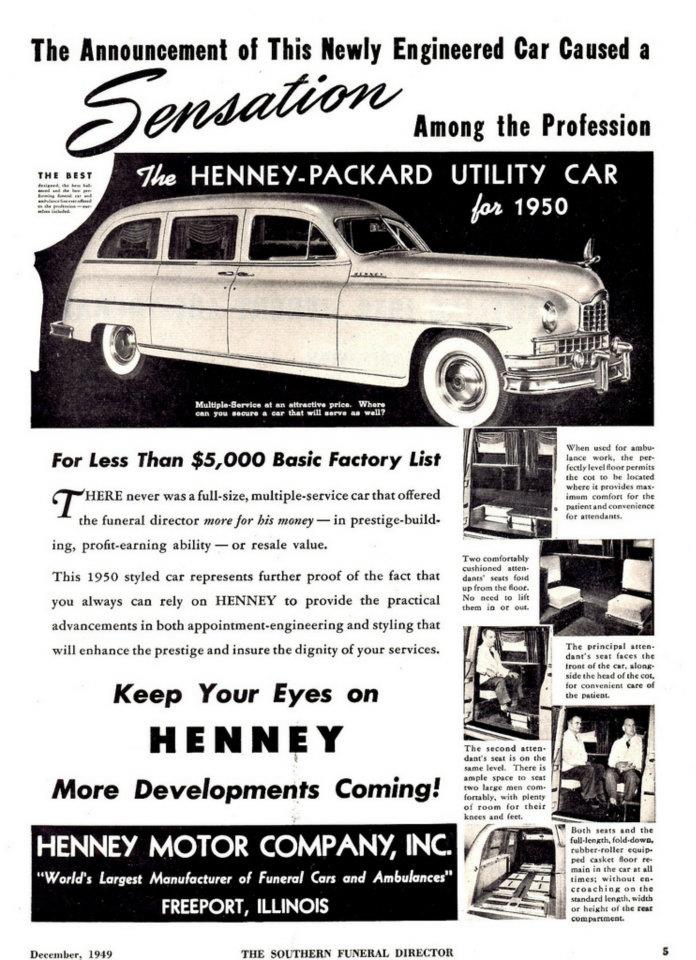

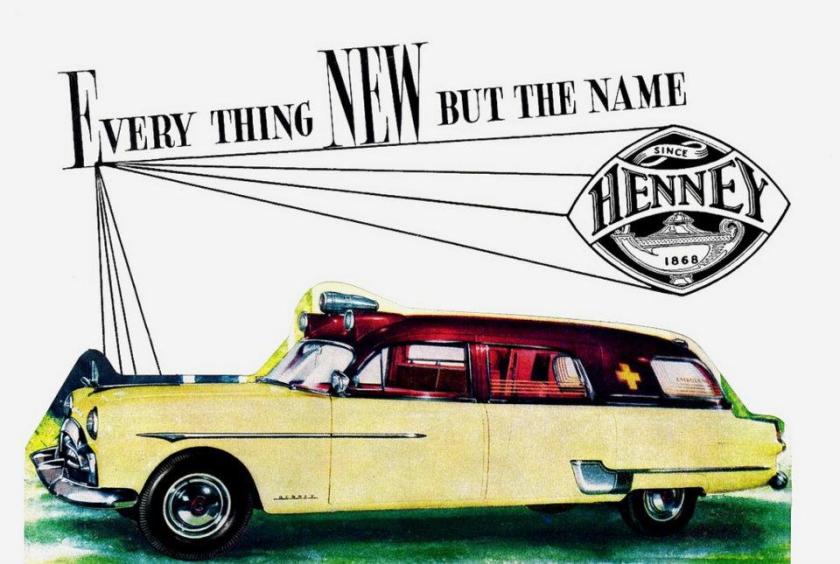

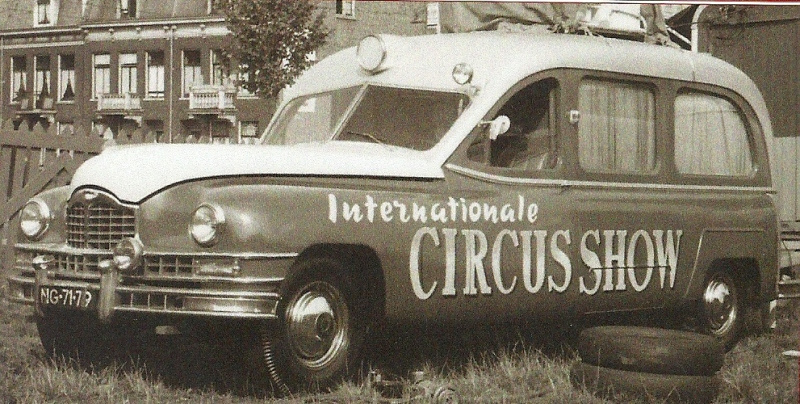

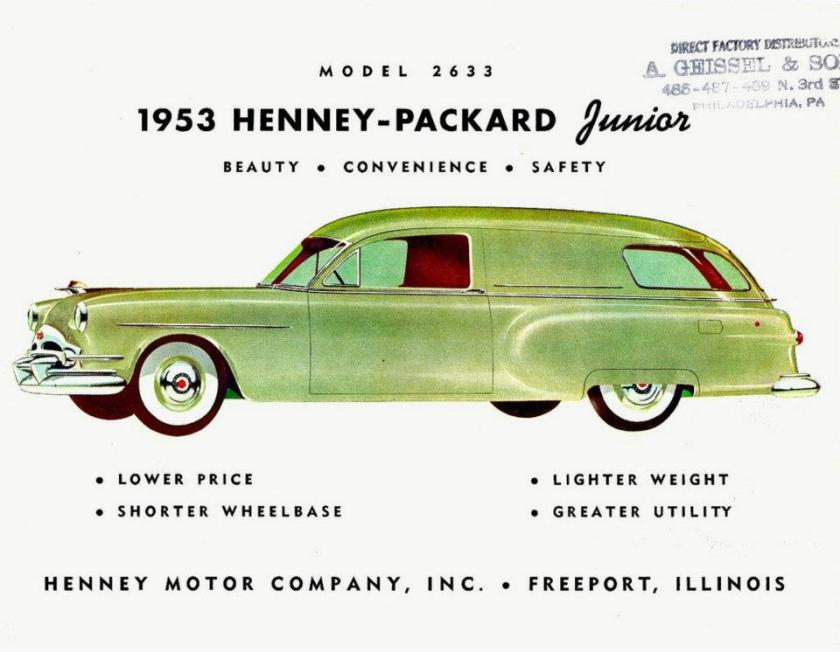

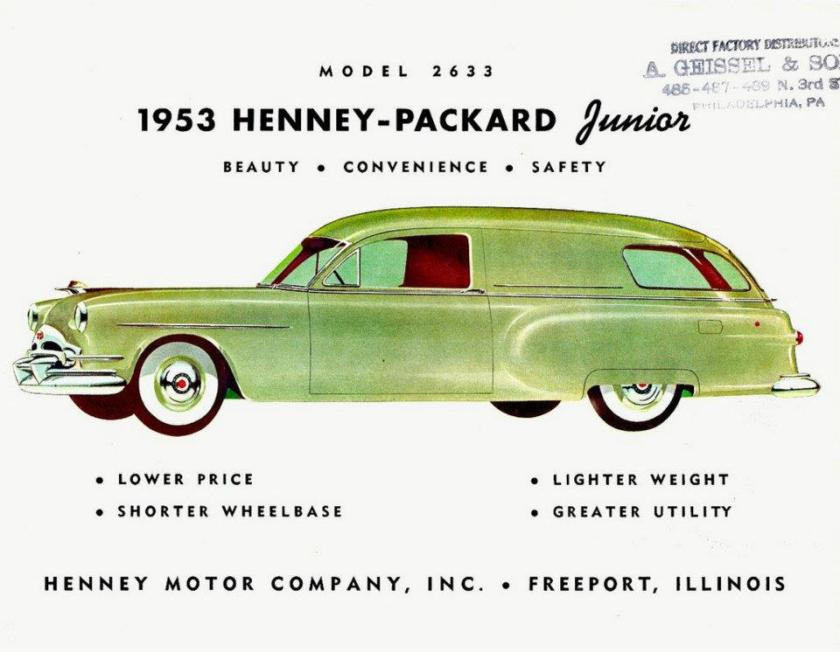

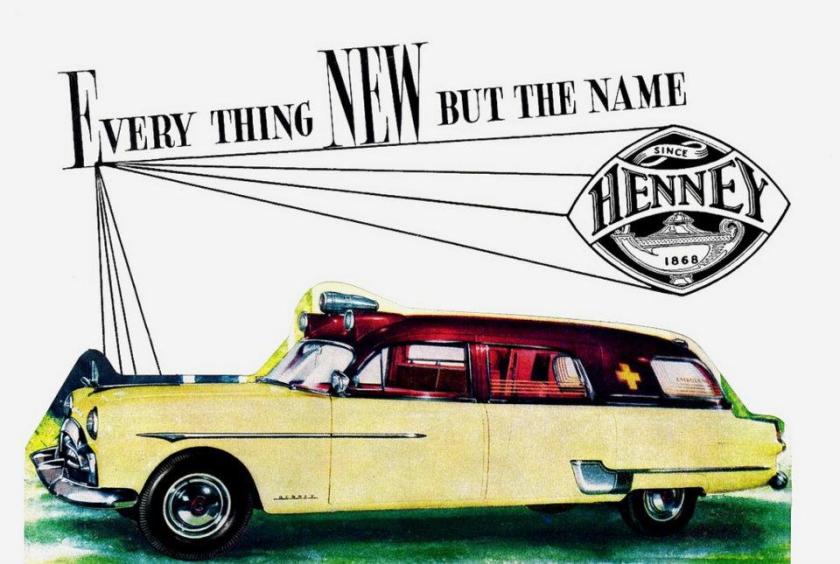

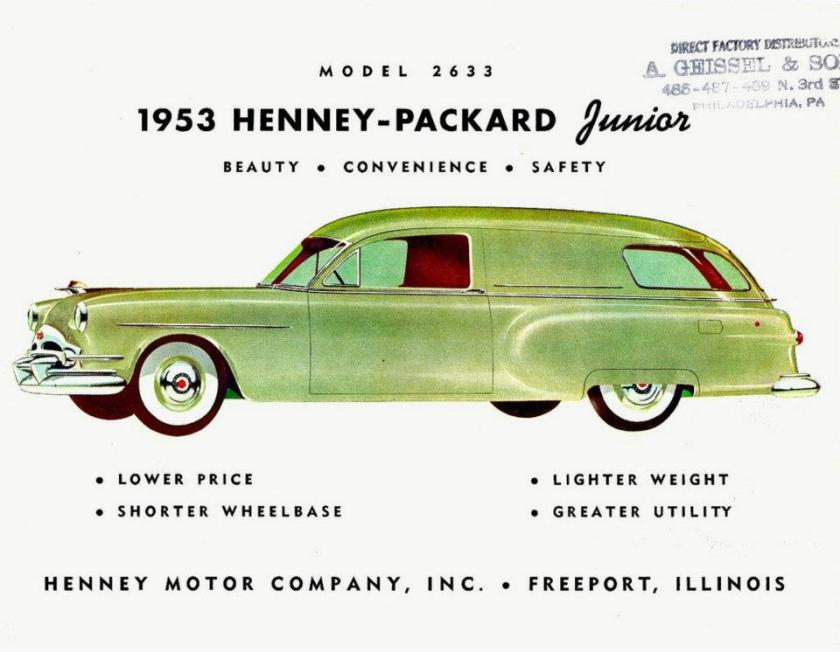

1953-henney-packard-junior-ambulanz-modell-2601-basierte-auf-dem-clipper-special

1953-packard-caribbean-convertible-water-mill

1953-packard-caribbean-sports-convertible-modell-2631-2678-in-matador-maroon-metallic

1953-packard-caribbean

1953-packard-carribean

1953-packard-cavalier-touring-sedan-modell-2602-2672-in-carolina-cream

1953-packard-cavalier

1953-packard-clipper-deluxe-touring-sedan-modell-2662

1953-packard-mayfair-hardtop-modell-2631-2677

1953-packard-mayfair

1953-packard

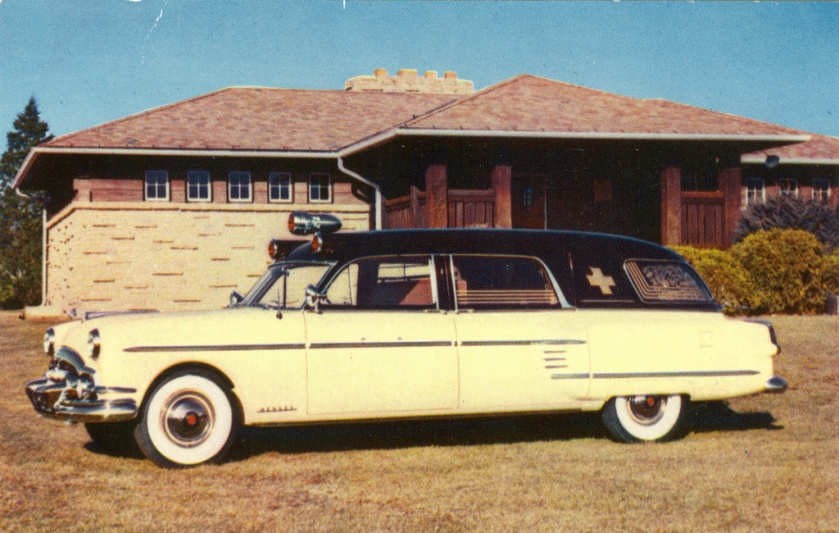

1954-henney-packard

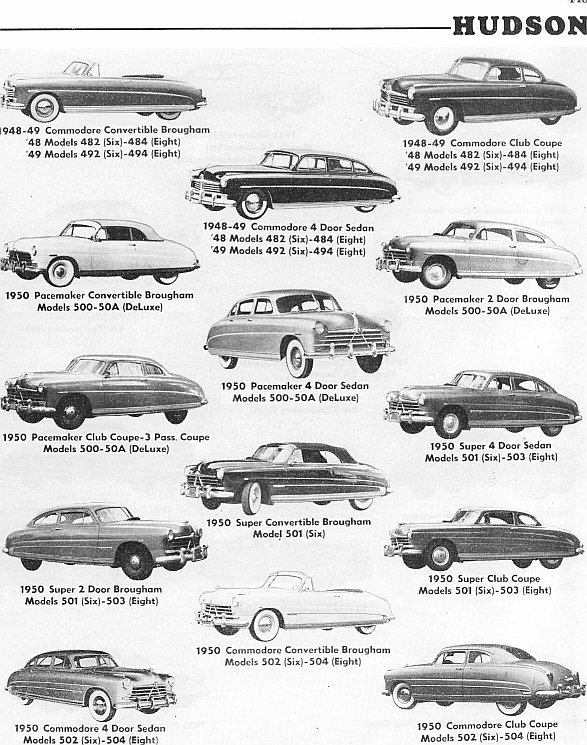

1954-hudson-super-wasp-hollywood-hardtop-das-step-down-design-von-1948-im-letzten-produktionsjahr

1954-nash-ambassador-super-sedan-grunddesign-von-1952-mit-etwas-beteiligung-von-pininfarina-am-entwurf

1954-nash-metropolitan-coupé

1954-packard-caribbean-2631

1954-packard-caribbean-convertible

1954-packard-clipper-super-panama-model-5467

1954-packard-convertible-modell-5479

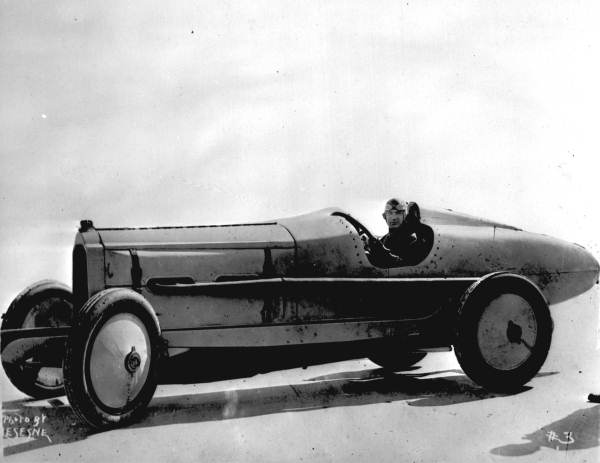

1954-packard-gray-wolf II

1954-packard-junior-persfoto

1954-packard-pacific-modell-5431-5477

1954-packard-panther-concept-car

1954-packard-panther-convertible-designed-by-dick-teague

1954-packard-panther-daytona-front

1954-packard-panther-daytona-goud-zwart

1954-packard-panther-daytona-kleur

1954-packard-panther-daytona

1954-packard-panther-daytona

1954-packard-panther

1954-packard-stradablog-2.

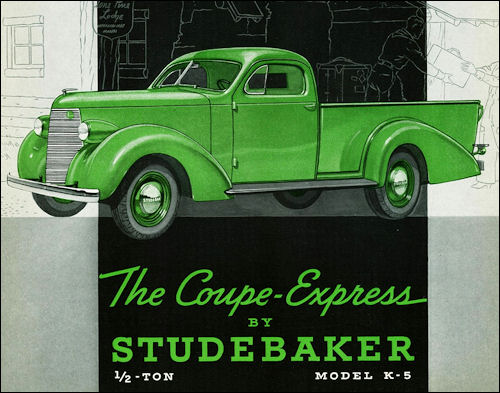

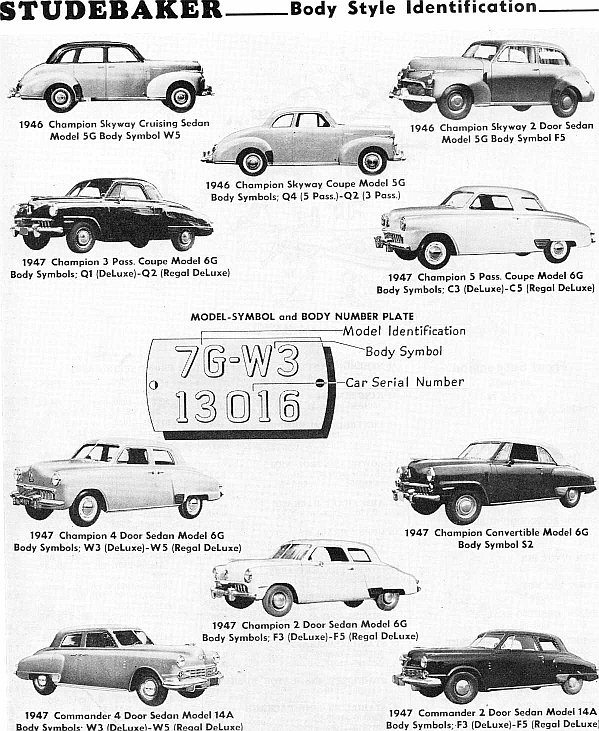

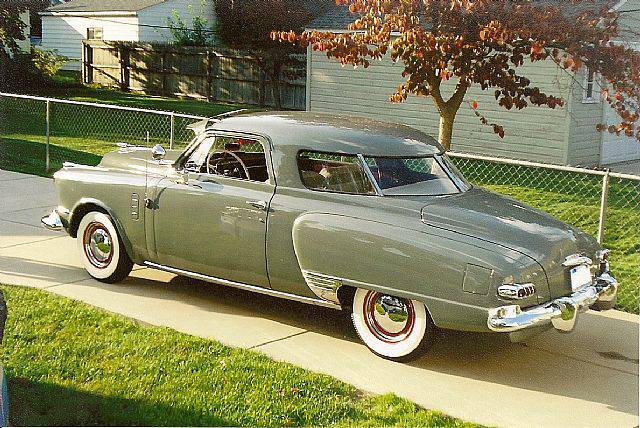

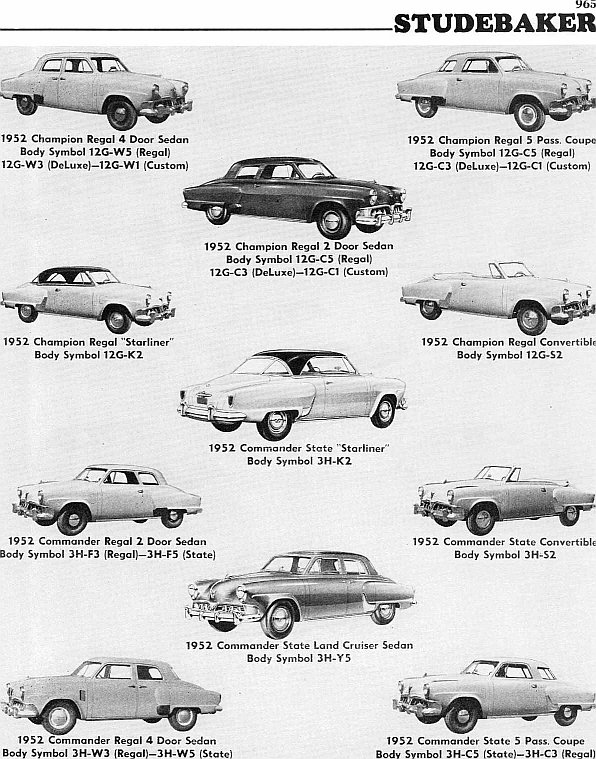

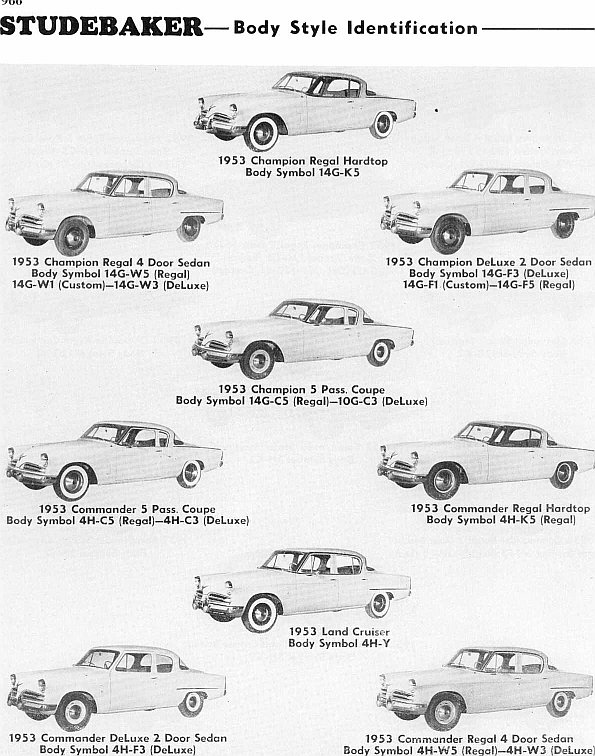

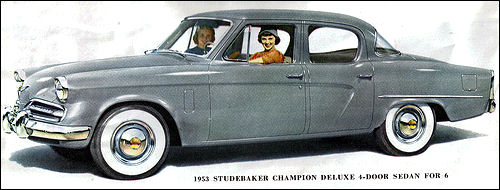

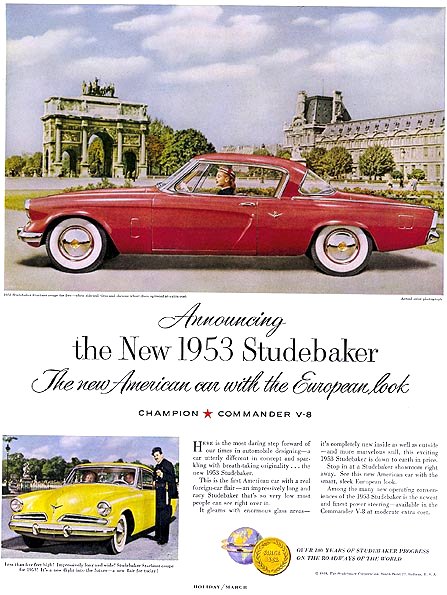

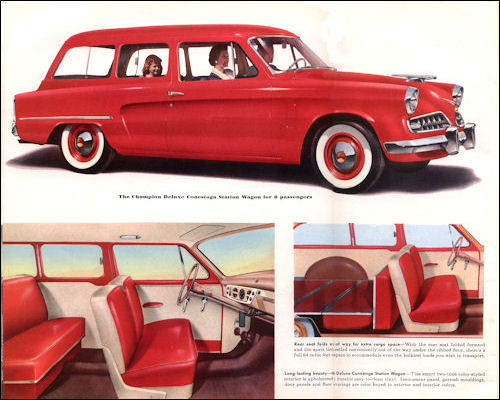

1954-studebaker-champion-sedan-facelift-eines-1953-eingefärten-neuen-designs-von-raymond-loewy-der-champion-war-das-basismodell-des-neuen-konzerns

1955-packard-caribbean-convert-va-I

1955-packard-caribbean-convertable-front-left

1955-packard-caribbean

1955-packard-clipper-custom-touring-sedan-modell-5562-spctere-ausfürung-mit-gebogenem-vorderen-zierstab

1955-packard-convertible-concept

1955-packard-four-hundred-hardtop-modell-5587-mit-optionalen-speichenrädern-von-kelsey-hayes

1955-pontiac-star-chief-catalina-hardtop-mit-fast-identischer-farbtrennung-wie-beim-packard-clipper

1955 + 57-packard-deluxe-super-eight-50-buick-roadmaster-55-buick-roadmaster-57

1955-packard-patrician-4dr-sedan-rear

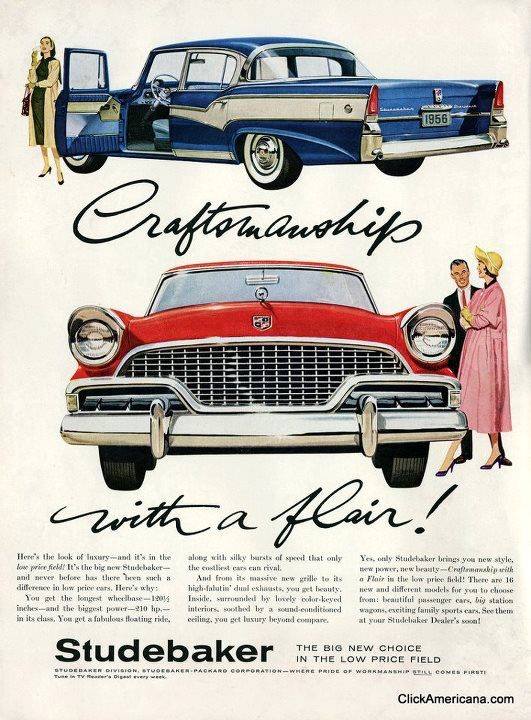

1956-packard-400

1956-packard-caribbean-convertible-bonhams

1956-packard-caribbean-convertible

1956-packard-caribbean-hardtop-modell-5697

1956-packard-caribbean-hardtop-modell-5697

1956-packard-caribbean-hardtop-modell-5697

1956-packard-caribbean

1956-packard-clipper-4-door-sedan

1956-packard-executive-5670-sedan

1956-packard-executive-5677-2

1956-packard-executive-5677-6

1956-packard-executive-hardtop-modell-5677

1956-packard-patrician-5580

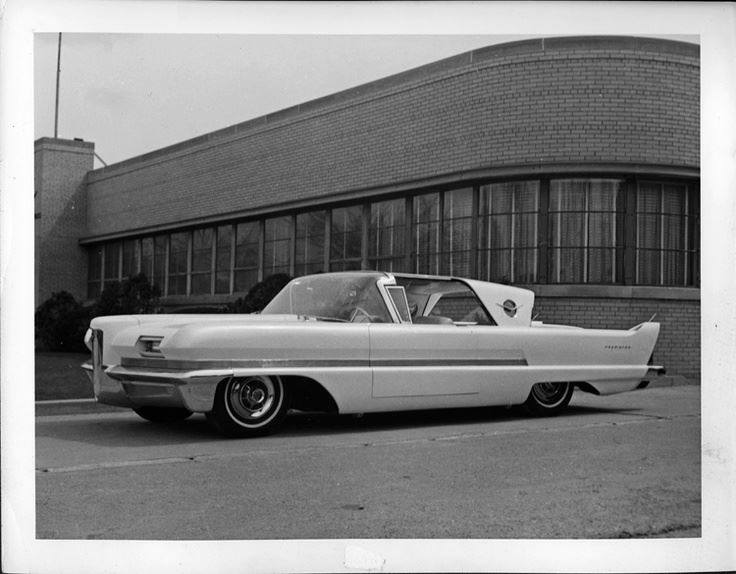

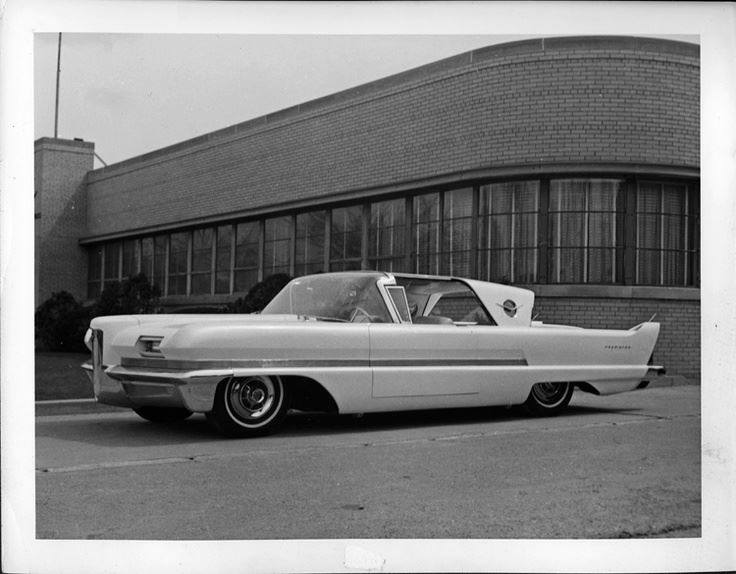

1956-packard-predictor-concept-car

1956-predictor-concept-at-the-studebaker-national-museum

1956-tri-toned-packard-caribbean-coupe

By the end of World War II, Packard was in excellent financial condition, but several management mistakes became ever more visible as time went on. Like other U.S. auto companies, Packard resumed civilian car production in late 1945 labeling them as 1946 models by modestly updating their 1942 models. As only tooling for the Clipper was at hand, the Senior-series cars were not rescheduled. One version of the story is that the Senior dies were left out in the elements to rust and were no longer usable. Another long-rumored tale is that Roosevelt gave Stalin the dies to the Senior series, but the ZiS-110 state limousines were a separate design.

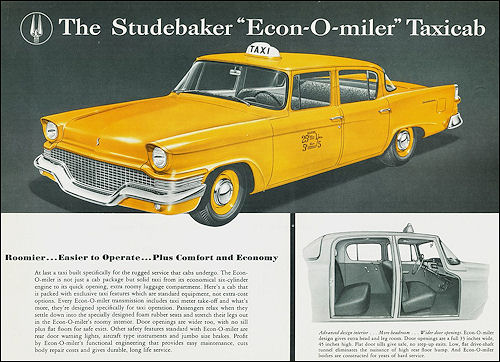

Although the postwar Packards sold well, the ability to distinguish expensive models from lower-priced models disappeared as all Packards, whether sixes or eights, became virtually alike in styling. Further, amidst a booming seller’s market, management had decided to direct the company more to volume middle-class models, thus concentrating on selling lower-priced cars instead of more expensive — and more profitable — models. Worse, they also tried to enter the taxi cab and fleet car market. The idea was to gain volume for the years ahead, but that target was missed: Packard simply was not big enough to offer a real challenge to the Big Three, and they lacked the deep pockets a parent company could shelter them from as well as the model lineup to spread the pricing through.

As a result, Packard’s image as a luxury brand was further diluted. As Packard lost buyers of expensive cars, it could not find enough customers for the lesser models to compensate. The shortage of raw materials immediately after the war – which was felt by all manufacturers – hurt Packard more with its volume business than it would have had it had focused on the luxury specialty car market.

1949 Packard Convertible Coupé

1950 Packard Eight 4-Door Sedan

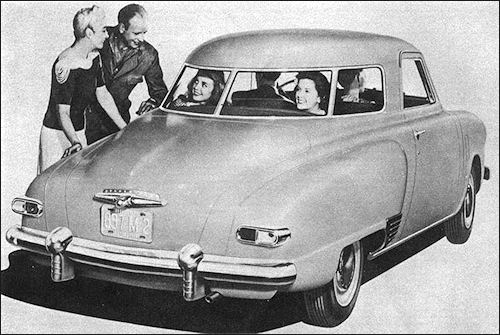

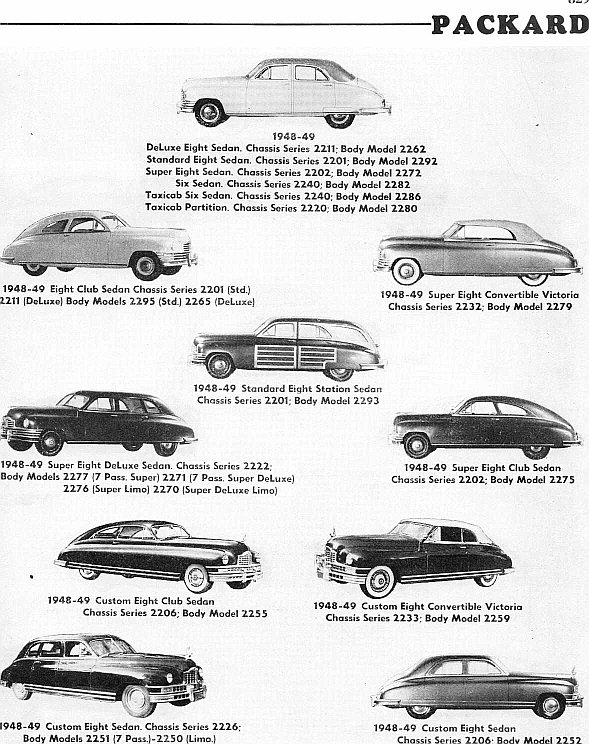

The Clipper, although a graceful classic automobile, became outdated as the new envelope bodies started appearing led by Studebaker and Kaiser-Frazer. Had they been a European car maker, this would have meant nothing; they could have continued to offer the classic shape not so different from the later Rolls-Royce with its vertical grill. Although Packard was in solid financial shape as the war ended, they had not sold enough cars to pay the cost of tooling for the 1941 design. While most automakers were able to come out with new vehicles for 1948-49, Packard could not do this until 1951. They therefore updated by adding sheet metal to the existing body (which added 200 pounds of curb weight). The design chosen was of the “bathtub” style, predicted during the war as the destined future of automobiles, and most fully realized by the 49/50 Nash. Six-cylinder cars were dropped for the home market, and a convertible was added.

These new designs hid their relationship to the Clipper. Even that name was dropped — for a while. However, it looked bulky, and was nicknamed the “pregnant elephant”. When a new body style was added, Packard introduced a station wagon instead of a 2-door hardtop as buyers requested. Test driver for Modern Mechanix, Tom McCahill, referred to the newly designed Packard as “a goat” and “a dowager in a Queen Mary hat”. Still, demand for any car was high and Packard sold 92,000 vehicles for 1948 and 116,000 of the 1949 models.

Packard abandoned the luxury car market, relinquishing the market to Cadillac. Although the Custom Clippers and Custom Eights were built in its old tradition with craftsmanship and the best materials, Cadillac now set the “Standard of the World”, with bold styling and tailfins. Cadillac was among the earliest U.S. makers to offer an automatic transmission (the Hydramatic in 1941), but Packard caught up with the Ultramatic, offered on top models in 1949 and all models from 1950 onward. Packard outsold Cadillac until about 1950; the problem was that most sales were the mid range lines, the volume models. A buyer of a Super Eight paying premium dollars did not enjoy seeing a lesser automobile with nearly all the Super Eight’s features, with just slight distinction in exterior styling. In addition to standard sedans, coupes, and convertibles, Packard also produced the curious “Station Sedan”, a wagon-like body that was mostly steel, but had a little structural and a good deal of decorative wood in the back. A total of 3,864 were sold over its three years of production.

Also in mid-1949, Packard introduced its Ultramatic automatic transmission, the only independent automaker to develop one. Although smoother than the GM Hydramatic, acceleration was sluggish and owners were often tempted to put it into Low Gear for faster starts which put extra wear on the transmission.

In 1950, sales tanked as the company sold only 42,000 cars for the model year. When Packard’s president George T. Christopher announced that the “bathtub” would get another facelift for 1951, influential parts of the management revolted. Christopher was forced to resign and loyal Packard treasurer Hugh Ferry became president.

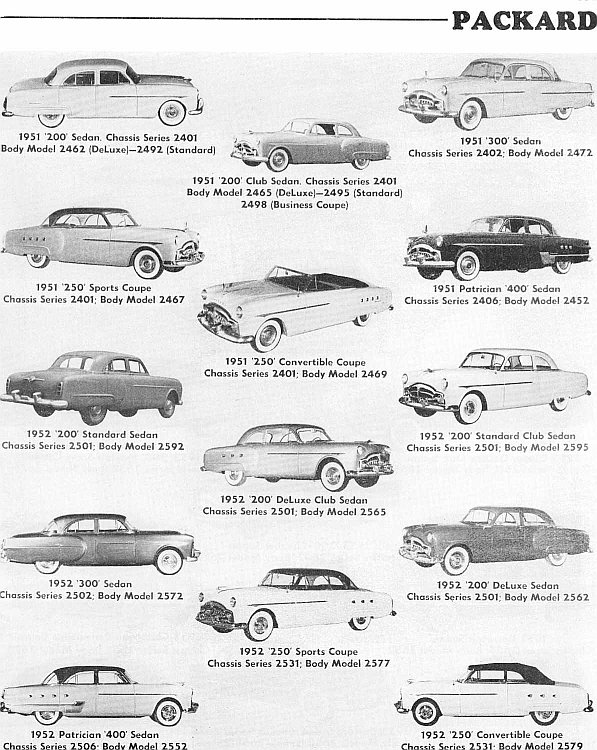

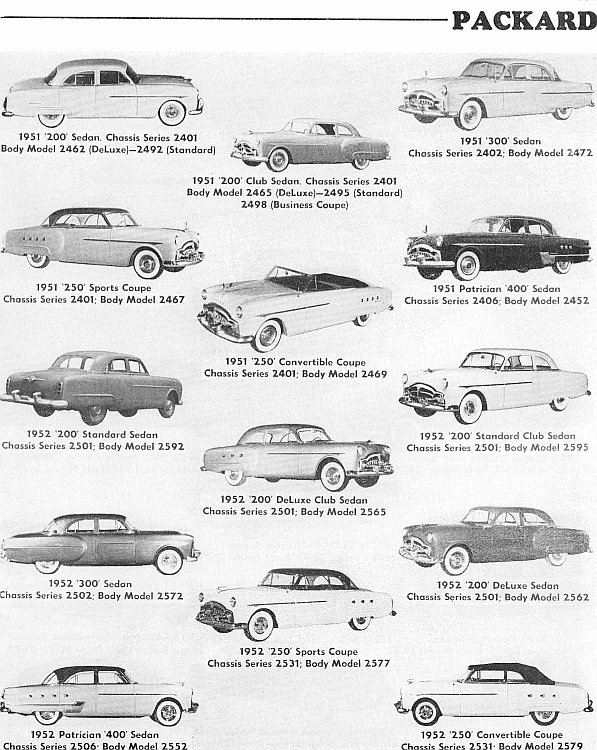

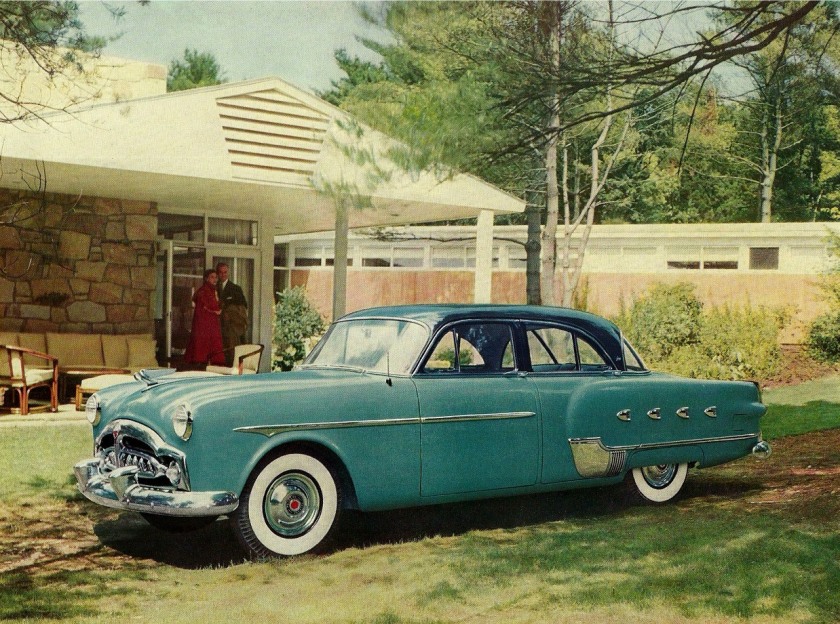

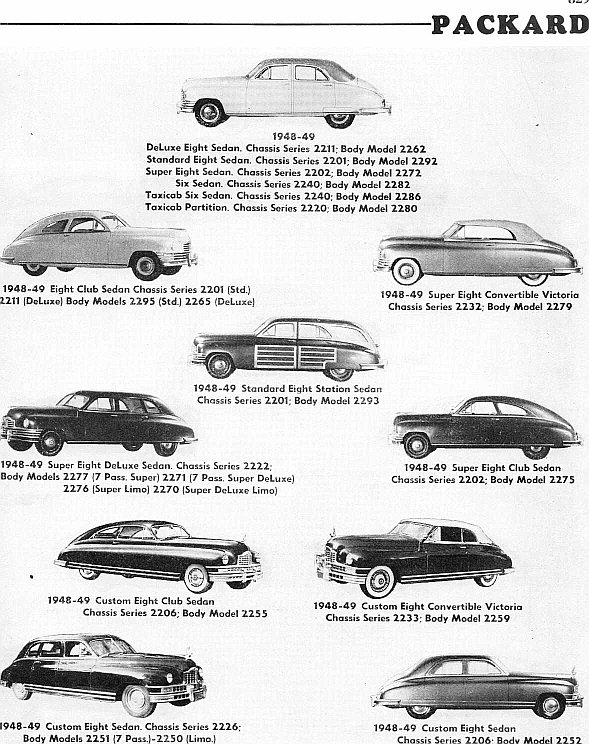

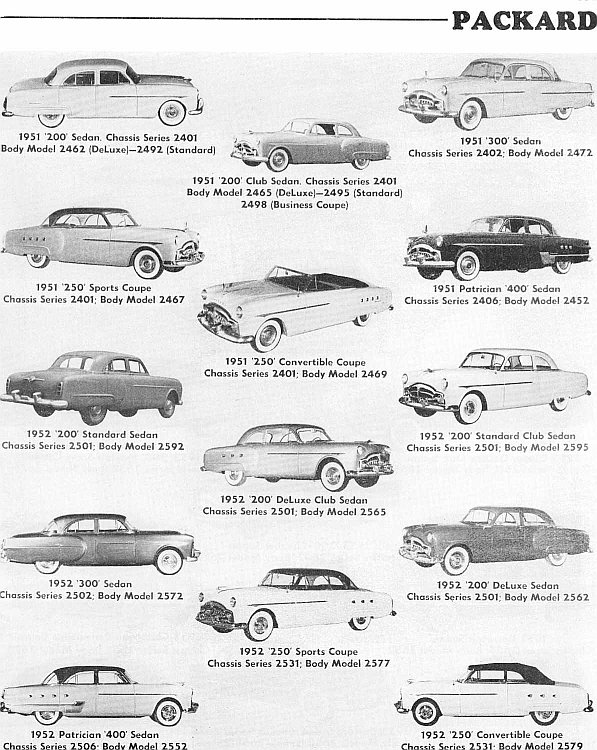

The 1951 Packards were at last completely redesigned. Designer John Reinhart introduced a high, more squared-off profile that was sleek and contemporary and looked as far from the bathtub design of 1948-50 as one could get. New styling features included a one-piece windshield, a wrap-around rear window, small tailfins on the long-wheelbase models, a full-width grill, and “guideline fenders” with the hood and front fenders at the same height. The 122-inch (3,099 mm) wheelbase supported low-end 200-series standard and Deluxe two and four doors, and 250-series Mayfair hardtop coupes (Packard’s first) and convertibles. Upmarket 300 and Patrician 400 models rode a 127-inch (3,226 mm) wheelbase. 200-series models were again low-end models and even included a business coupe.

The 250, 300, and 400/Patricians were Packard’s flagship models and comprised the majority of production for that year. The Patrician was now the top-shelf Packard, replacing the Custom Eight line. Original plans were to equip it with a 356 cu in (5.8 L) engine, but the company decided that sales would probably not be high enough to justify producing the larger, more expensive power plant, and so instead the debored 327 cu in (5.4 L) (previously the middle engine) was used instead and offered nearly equal performance.

Since 1951 was a quiet year with little new from the other auto manufacturers, Packard’s redesigned lineup sold nearly 101,000 cars. The last new Packards ever produced were a quirky mixture of the ultra-modern (the automatic transmissions) and the archaic (still using flathead inline eights when OHV V8 engines were about to become the norm). No domestic car lines had OHV V8s in 1948, but by 1955, every car line offered a version. The Packard inline eight, despite being a very long-in-the-tooth design that lacked the power of Cadillac’s engines, was very smooth and combined with an Ultramatic transmission, made for a nearly noiseless interior on the road.

Packard did well during the early post-war period and supply soon caught up with demand. By the early 1950s, the independent American manufacturers were left moribund as the “Big Three” – General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler – battled intensely for sales in the economy, medium-price, and luxury market. Those independents that remained alive in the early Fifties, merged. In 1953 Kaiser merged with Willys to become Kaiser-Willys. Nash and Hudson became American Motors (AMC). The strategy for these mergers included cutting costs and strengthening their sales organizations to meet the intense competition from the Big Three.

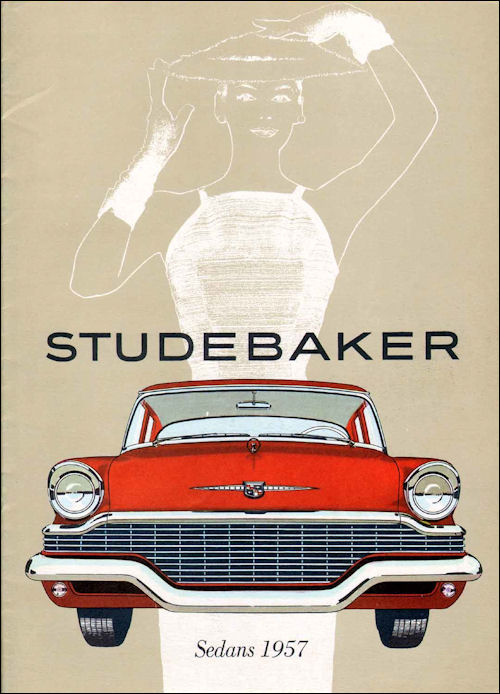

In May 1952, aging Packard president Hugh Ferry resigned and was succeeded by James J. Nance, a marketing hotshot recruited from Hotpoint to turn the stagnant company around (its main factory on Detroit’s East Grand Boulevard was operating at only 50% capacity). Nance worked to snag Korean War military contracts and turn around Packard’s badly diluted image. He declared that from now on, Packard would cease producing mid-priced cars and build only luxury models to compete with Cadillac.

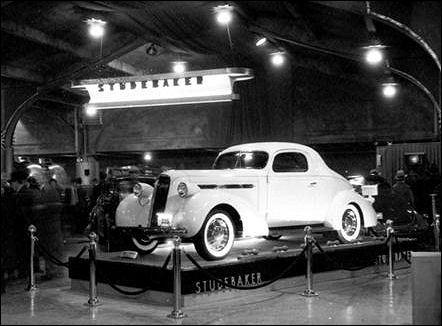

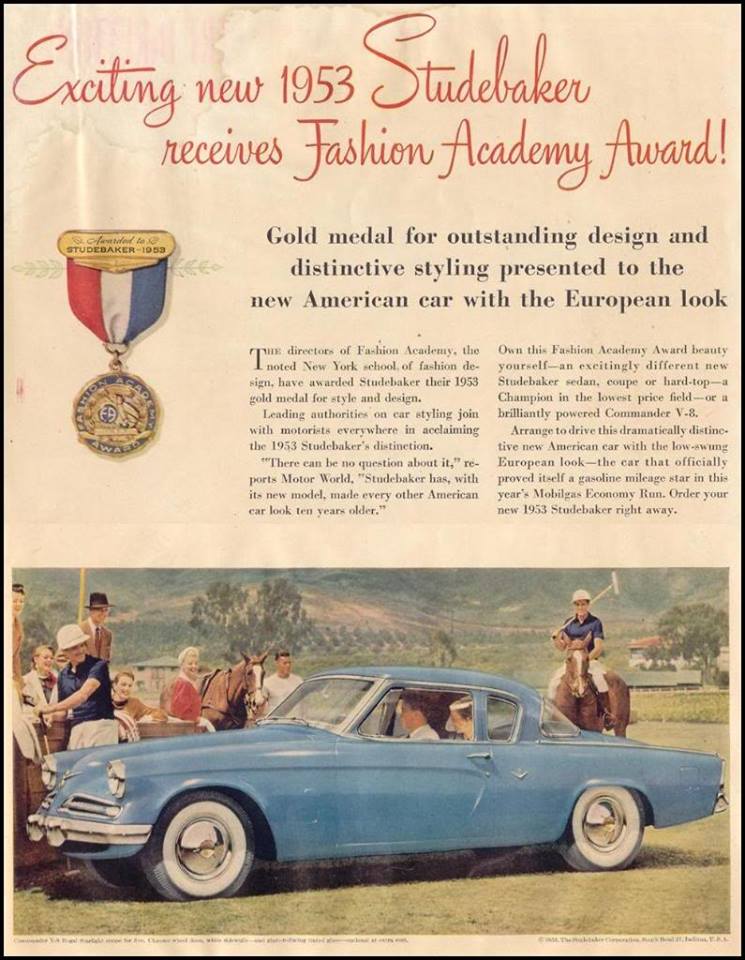

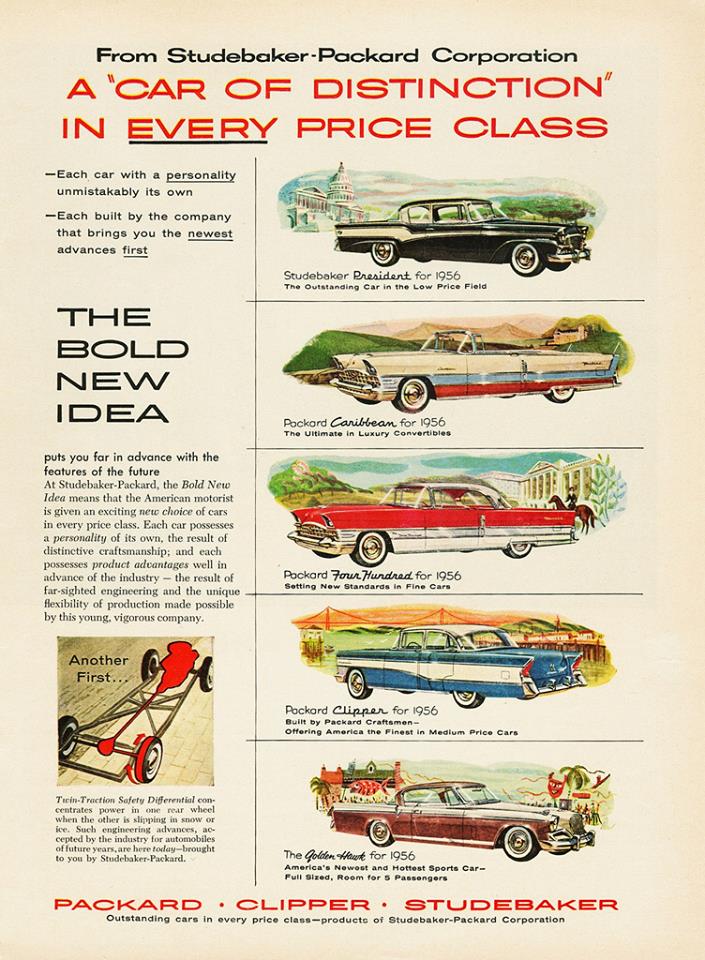

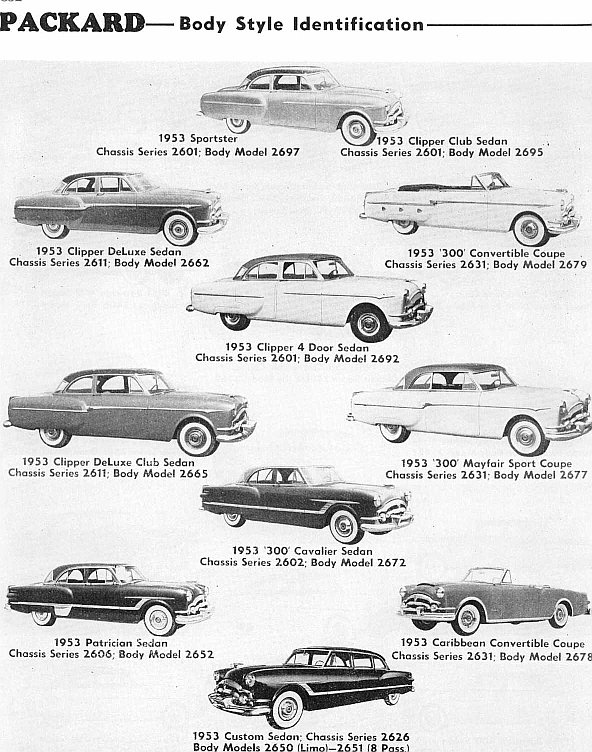

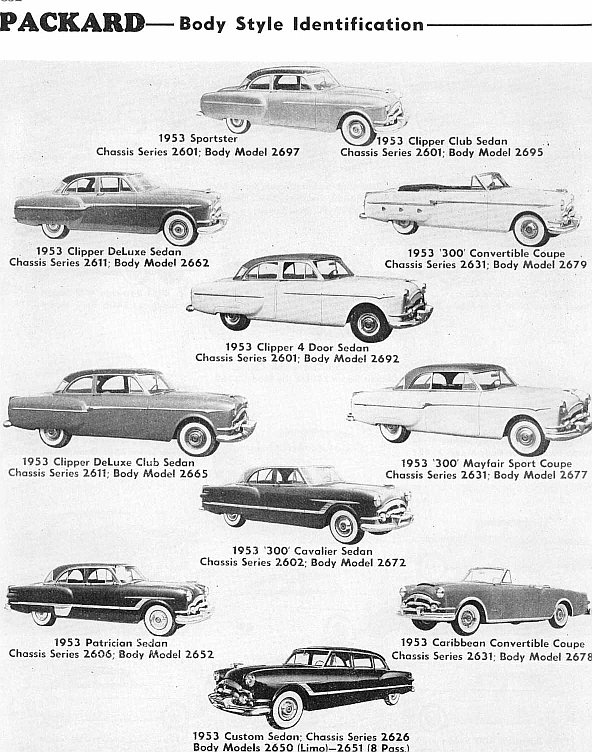

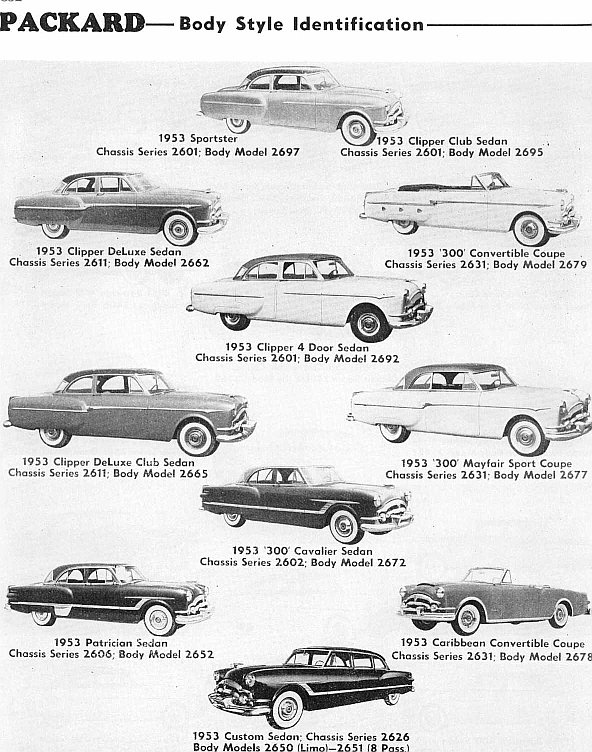

As part of this strategy, Nance unveiled a low-production (only 750 made) glamour model for 1953, the Caribbean convertible. Competing directly with the other novelty ragtops of that year (Buick Skylark, Oldsmobile Fiesta, and Cadillac Eldorado), it was equally well received, and outsold its competition.

Nance had hoped for a total redesign in 1954, but the necessary time and money were lacking. Packard that year (total production 89,796) comprised the bread-and-butter Clipper line (the 250 series was dropped), Mayfair hardtop coupes and convertibles, and a new entry level long-wheelbase sedan named Cavalier. Among the Clippers was a novelty pillared coupe, the Sportster, styled to resemble a hardtop.

With time and money again lacking, the 1954 lineup was unchanged except for modified headlights and taillights, essentially trim items. A new hardtop named Pacific was added to the flagship Patrician series and all higher-end Packards sported a bored-out 359-cid engine. Air conditioning became available for the first time since 1942. Packard had introduced air conditioning in the 1930s. Clippers (which comprised over 80% of production) also got a hardtop model, Super Panama. But sales tanked, falling to only 31,000 cars.

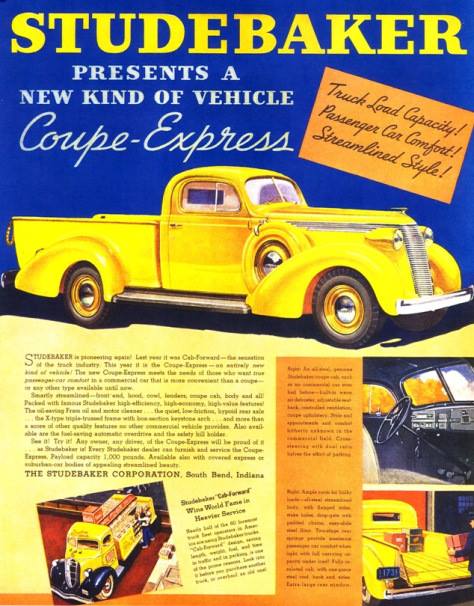

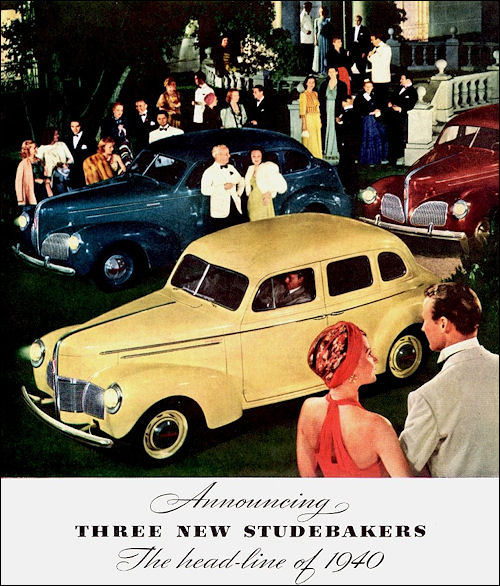

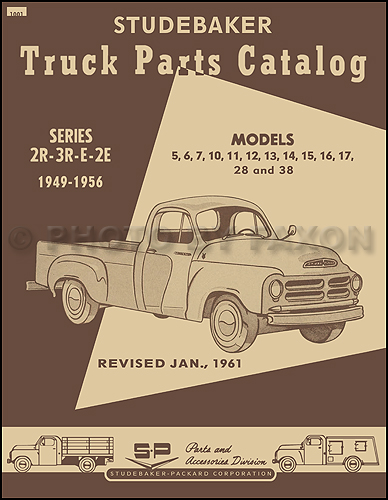

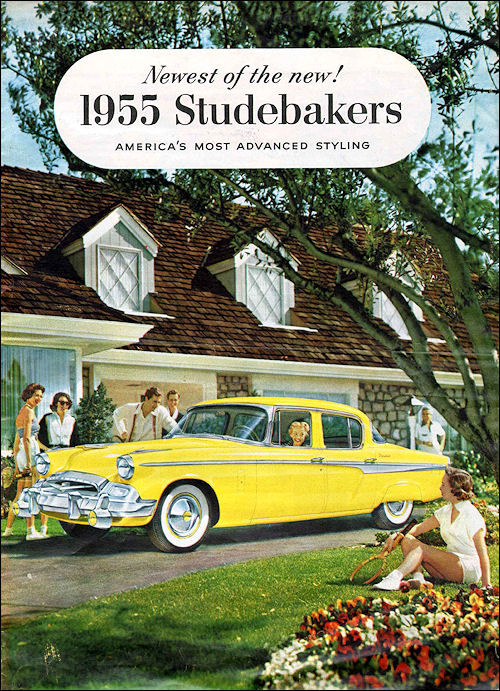

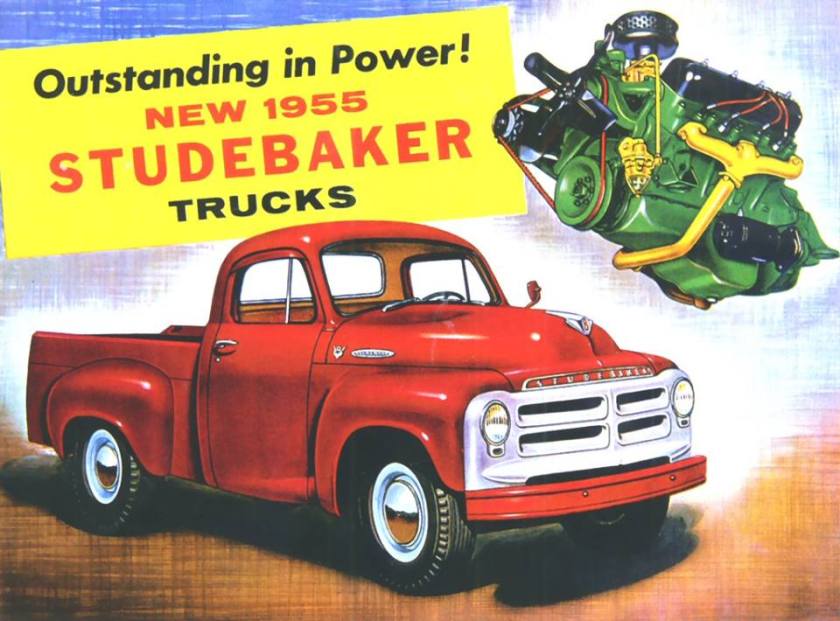

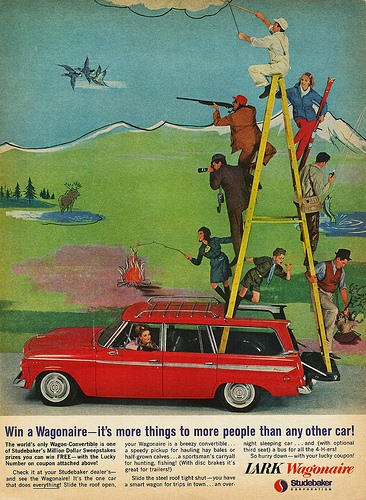

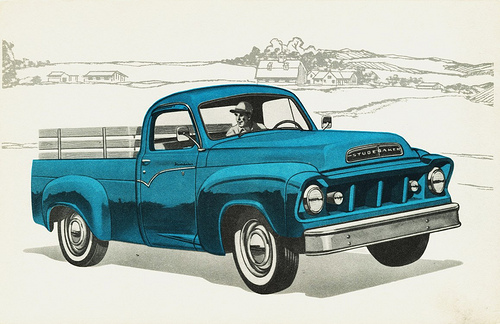

The revolutionary new model Nance hoped for was delayed until 1955, partially because of Packard’s merger with Studebaker. In 1953-54, Ford and GM waged a brutal sales war, cutting prices and forcing cars on dealers. While this had little effect on either company, it gravely damaged the independent auto makers. Nash president George Mason thus proposed that the four major independents (Nash, Hudson, Packard, and Studebaker) all merge into one large outfit to be named American Motors Corporation. Mason held informal discussions with Nance to outline his strategic vision, and an agreement was reached for AMC to buy Packard’s Ultramatic transmissions and V8 engines, and they were used in 1955 Hudsons and Nashes. However, SPC’s Nance refused to consider merging with AMC unless he could take the top command position (Mason and Nance were former competitors as heads of the Kelvinator and Hotpoint appliance companies respectively). But Mason’s grand vision of a Big Four American auto industry ended in October 1954 with his sudden death from a heart attack. A week after the death of Mason, the new president of AMC, George W. Romney announced “there are no mergers under way either directly or indirectly.” Nevertheless, Romney continued with Mason’s commitment to buy components from SPC. Although Mason and Nance had previously agreed that SPC would purchase parts from AMC, it did not do so. Moreover Packard’s engines and transmissions were comparatively expensive, so AMC began development of its own V8 engine, and replaced the outsourced unit by mid-1956.

Although Nash and Hudson merged along with Studebaker and Packard joining, the four-way merger Mason hoped for did not materialize. The S-P marriage (really a Packard buyout), proved to be a crippling mistake. Although Packard was still in fair financial shape, Studebaker was not, struggling with high overhead and production costs and needing the impossible figure of 250,000 cars a year to break even.

Due diligence was not performed, and the merger was rushed. Studebaker’s management was notorious for building the wrong car at the wrong time, while the cars people wanted were always in short supply, strangling the company financially as a result.

In 1951 Packard replaced the old “bathtub” models with a new and more modern body that resembled typical cars of the early 1950s. Sales were slower by 1953, despite Packard’s push to recapture the luxury market with such limited edition luxury models as the Caribbean convertible and the Patrician 400 Sedan, and the Derham custom formal sedan, In 1954, Packard stylist Richard A. Teague was called upon by Nance to redesign the 1955 model. To Teague’s credit, the 1955 Packard was indeed a sensation when it appeared, gaining greater acceptance than anticipated. Not only was the body completely updated and modernized, but the suspension was totally new, with torsion bars front and rear, along with an electric load-leveler control that kept the car level regardless of load or road conditions. Crowning this stunning new design was Packard’s first modern overhead-valve V8, displacing 352 cu in (5.8 l), replacing the old, heavy, cast-iron side valve straight-eight that had been used for decades. In addition, Packard offered the entire host of power comfort and convenience features, such as power steering and brakes, electric window lifts, and air conditioning (even in the Caribbean convertible), a Packard exclusive at the time. Sales rebounded to 101,000 for 1955, although that was a very strong year across the industry.

As the 1955 models went into production, an old problem flared up. Back in 1941, Packard had outsourced its bodies to Briggs Manufacturing. In 1954, Chrysler bought out that company, ending Packard’s supply. They had to resume in-house production, which for unknown reasons was done in a cramped factory in West Detroit. This facility was too small and caused endless tie-ups and quality problems. Packard would have fared better building the bodies in its old, but amply-sized main facility on East Grand Boulevard. Bad quality control hurt the company’s image and caused sales to plummet for 1956 even though the problems had largely been resolved by that point.

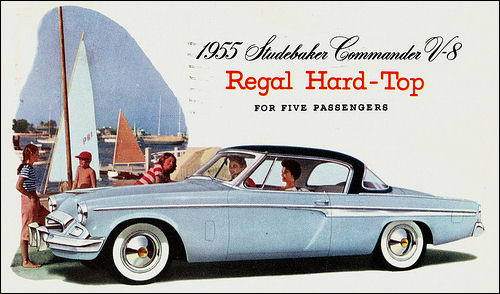

For 1956, the Clipper became a separate make, with Clipper Custom and Deluxe models available. Now the Packard-Clipper business model was a mirror to Lincoln-Mercury. “Senior” Packards were built in four body styles. Each body style had a unique model name. Patrician was used for the four-door top of the line sedans, Four Hundred was used for the hardtop coupes, and Caribbean was used for the convertible and hardtop vinyl-roof two-door hardtop models. In the spring of 1956 the Executive was introduced. Coming in a four-door sedan, and a two-door hardtop, the Executive was aimed at the buyer who wanted a luxury car but could not justify Packard’s pricing. It was an intermediate model using the Packard name and the Senior models’ front end, but built on the Clipper wheelbase and using the Clipper tail end fender treatment. This was to some confusing and went against what James Nance had been attempting for several years to accomplish, the separation of the Clipper line from Packard. However, as late as the cars introduction to the market, was there was reasoning for in 1957 this car was to be continued. It then become a baseline Packard on the all new 1957 Senior shell. Clippers would share bodies with Studebaker from 1957.

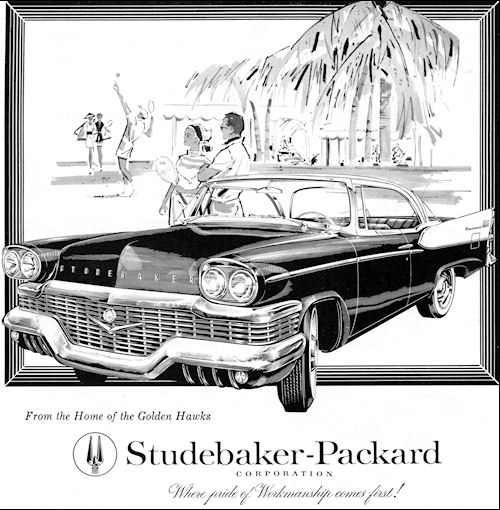

Despite the new 1955/56 design, Cadillac continued to lead the luxury market, followed by Lincoln, Packard, and Imperial. Reliability problems with the automatic transmission and all electrical accessories further eroded the public’s opinion of Packard. Sales were good for 1955 compared to 1954. The year was also an industry banner year. Packard’s sales slid in 1956 due to the fit and finish of the 1955 models, and mechanical issues relating to the new engineering features. These defects cost Packard millions in recalls and tarnished a newly won image just in its infancy. Along with Studebaker sales dragging Packard down, things looked more terminal than ever for SPC.

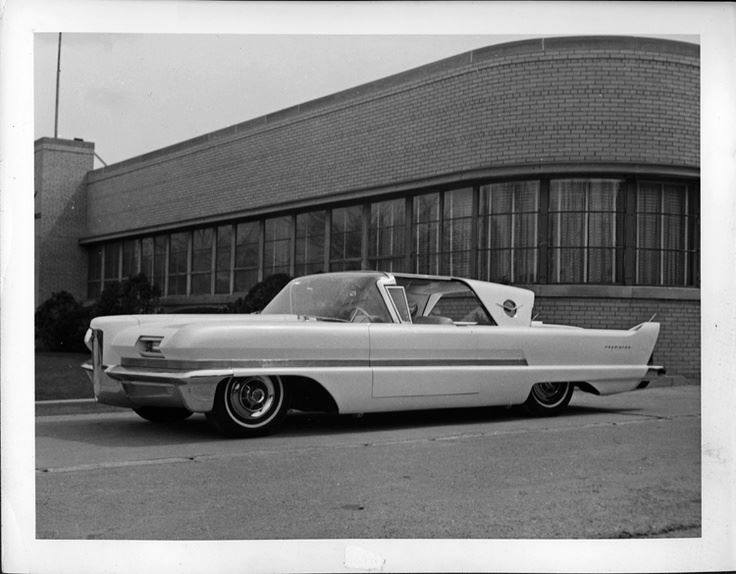

For 1956, Teague kept the basic 1955 design, and added more styling touches to the body such as then−fashionable three toning. Headlamps hooded in a more radical style in the front fenders and a slight shuffling of chrome distinguished the 1956 models. “Electronic Push-button Ultramatic,” which located transmission push buttons on a stalk off of the steering column, proved to be trouble-prone, adding to the car’s negative reputation, possibly soon to become an orphan. Model series remained the same, but the V8 was now enlarged to 374 cu in (6.1 L) for Senior series, the largest in the industry. In the top-of-the-line Caribbean, that engine produced 310 hp (230 kW). Clippers continued to use the 352 engine. There were plans for an all−new 1957 line of Senior Packards based on the showcar Predictor. Clippers and Studebakers would also share many inner and outer body panels. These models were in many ways far advanced from what would be produced by any automaker at the time, save Chrysler, which would soon feel public wrath for its own poor quality issues after rushing its all−new 1957 lines into production. James Nance was dismissed from Packard and moved to Ford as the head of the new MEL (Mercury-Edsel-Lincoln) division. Although Nance tried everything, the company failed to secure funding for new retooling; forcing Packard to share Studebaker platforms and body designs, but as badge-engineered models, not in the way it had been envisioned. With no funding to retool for the advanced new models envisioned, SPC’s fate was sealed; the large Packard was effectively dead in an executive decision to kill “the car we could not afford to lose”. The last Packard-designed vehicle, a Patrician 4-door sedan, rolled off the assembly line on June 25, 1956.

1957–1958

1957-packard-clipper-country-sedan-station-wagon

1958-packard

1958-packard-four-door-sedan-front

1958-packard-hardtop-coupe

1958-packard-hawk-modell-58

1958-packard-hawk-modell-58

1958-packard-hawk-modell-58

1958-packard-rear

1958-packard-station-wagon-1-of-159-built

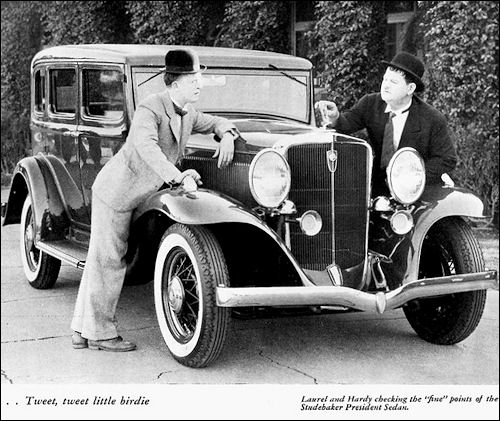

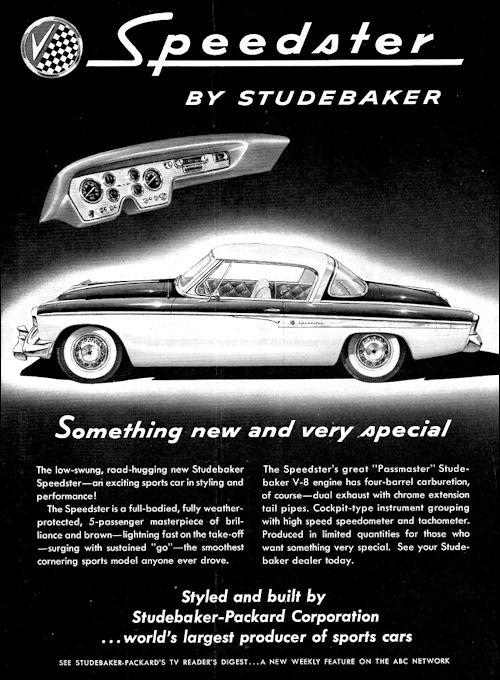

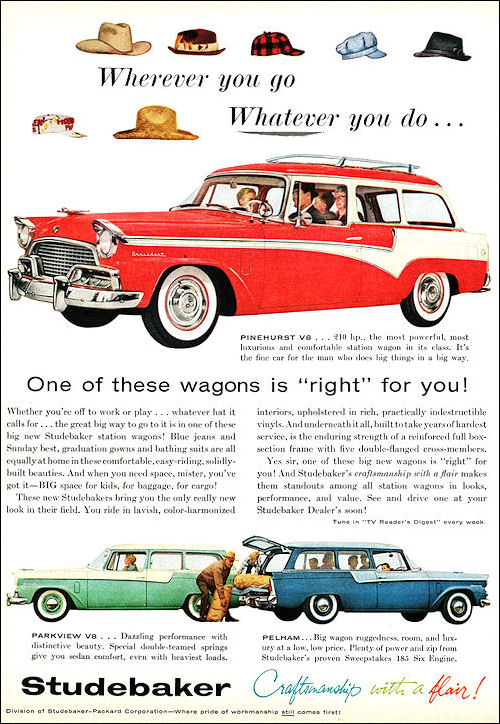

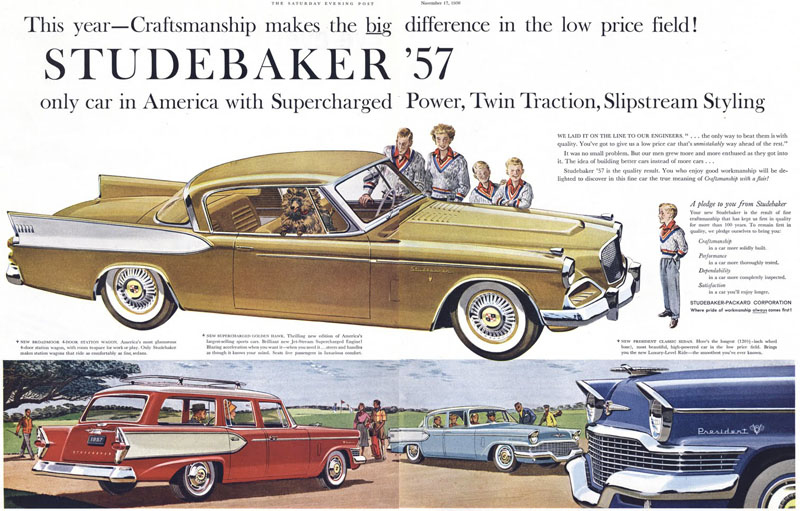

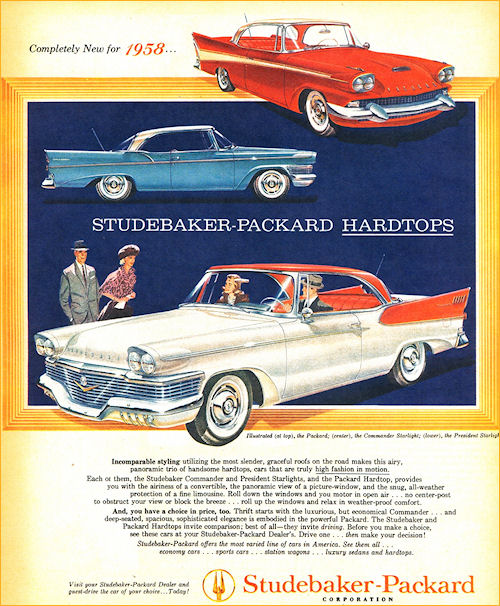

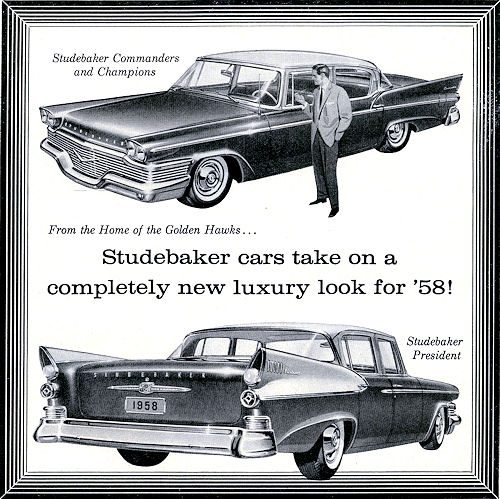

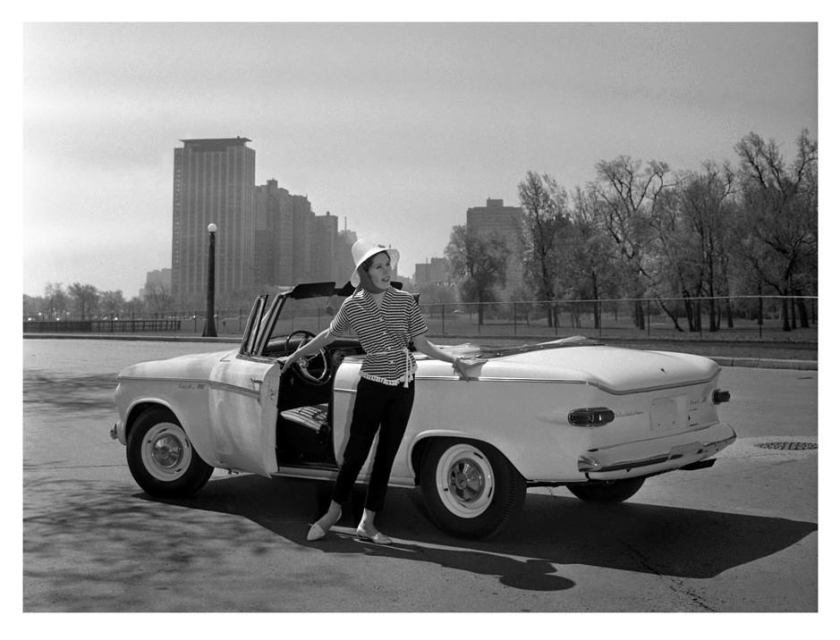

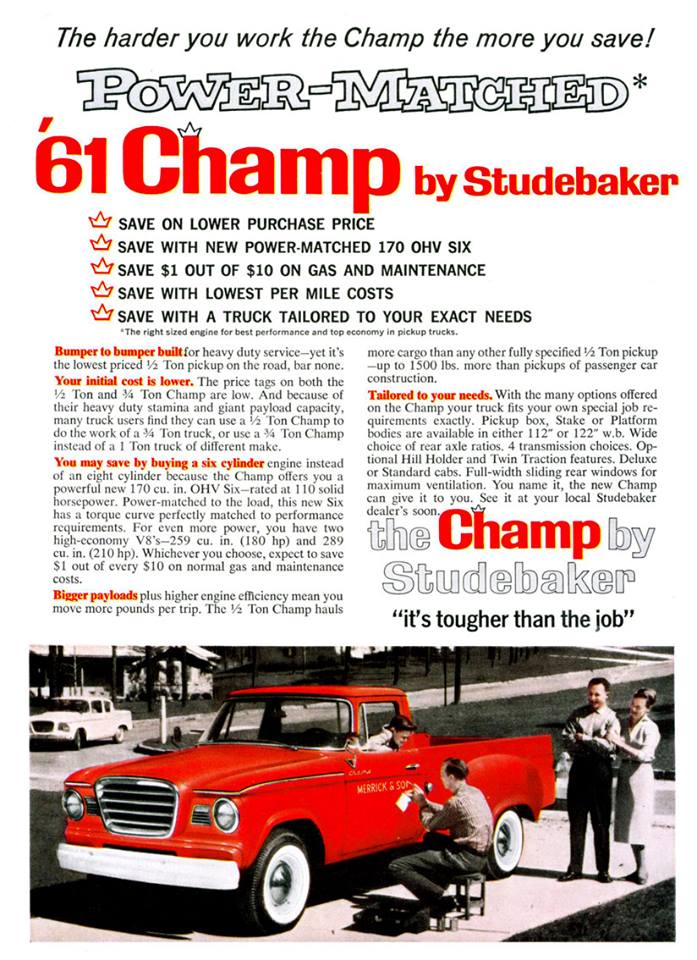

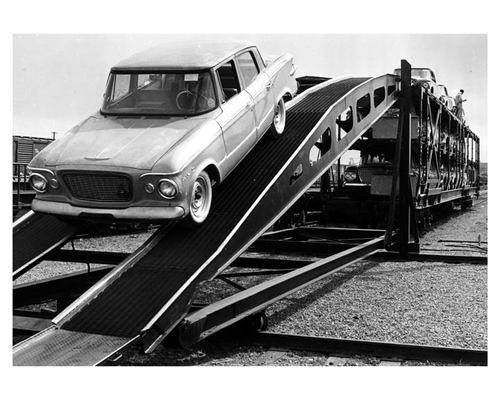

In 1957, no more Packards were built in Detroit and the Clipper disappeared as a separate brand name. Instead, a Studebaker President-based car bearing the Packard Clipper nameplate appeared on the market, but sales were slow. Available in just two body styles, Town Sedan (4-door sedan) and Country Sedan (4-door station wagon), they were powered by Studebaker’s 289 cu in (4.7 l) V8 with McCulloch supercharger, delivering the same 275 hp (205 kW) as the 1956 Clipper Custom, although at higher revolutions.

While the 1957 Packard Clipper was less Packard, it was a very good Studebaker. The cars sold in limited numbers, which was attributed to Packard dealers dropping their franchises and consumers fearful of buying a car that could soon be an orphaned make. It was tried with design cues from the 1956 Clipper (visual in the grille and dash). Wheel-covers, tail-lamps and dials were stock 1956 parts, as was the Packard cormorant hood mascot and trunk chrome trim from 1955 senior Packards.

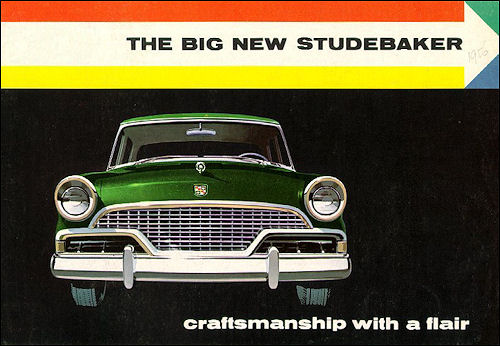

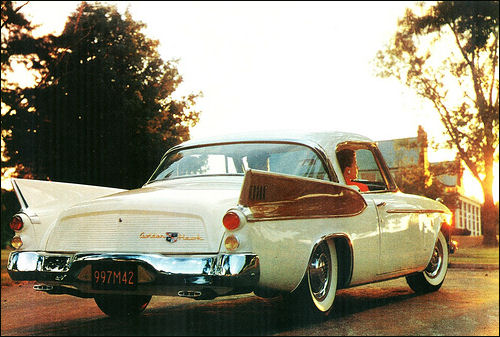

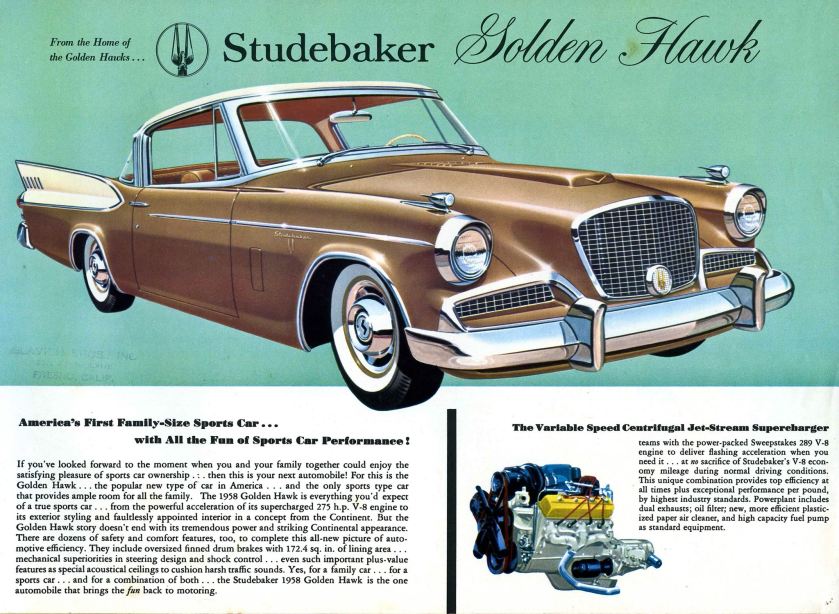

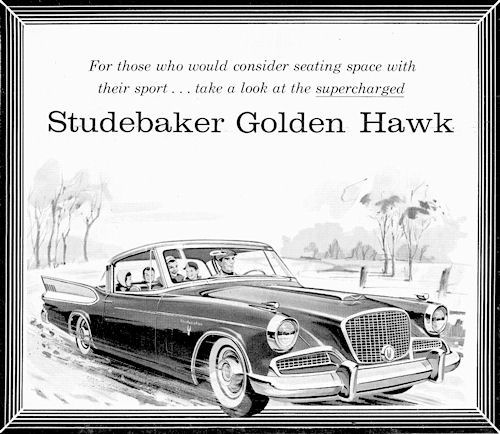

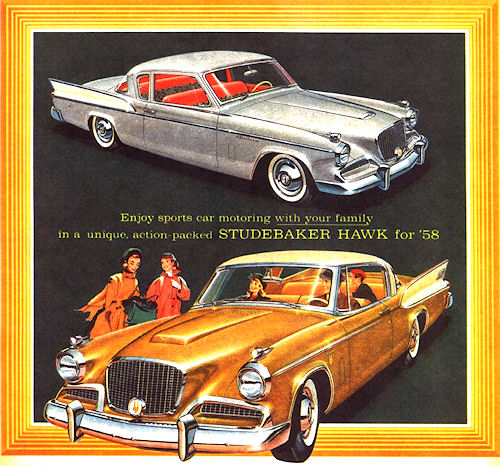

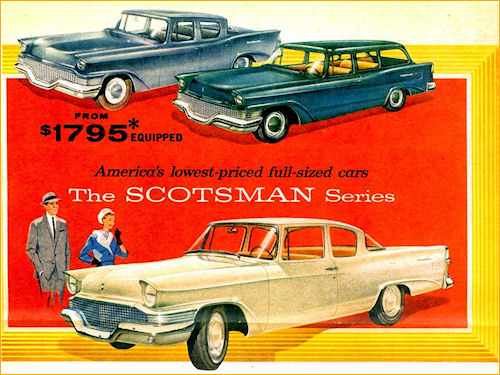

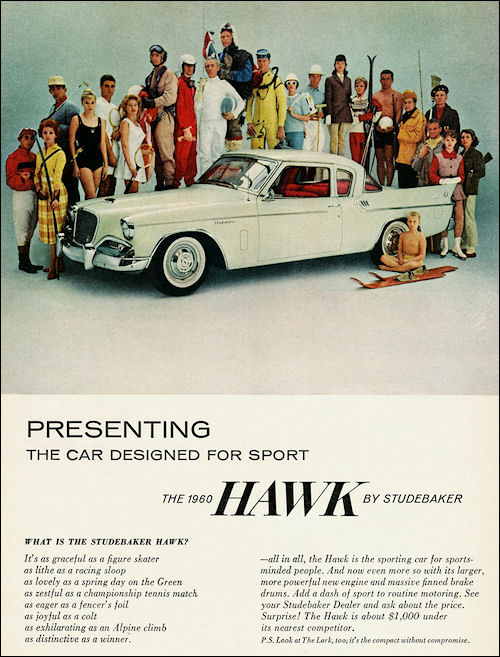

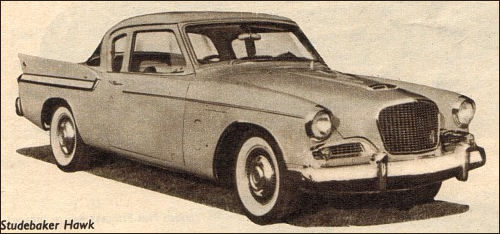

The 1958 models were launched with no series name, simply as “Packard”. More styles were added, a 2-door hardtop and 4-door sedan, and as the premier model, a Packard Hawk that was a Studebaker Golden Hawk with a new front, a fake spare wheel molded in the trunk lid reminiscent of the concurrent Imperial, and Packard styling cues.

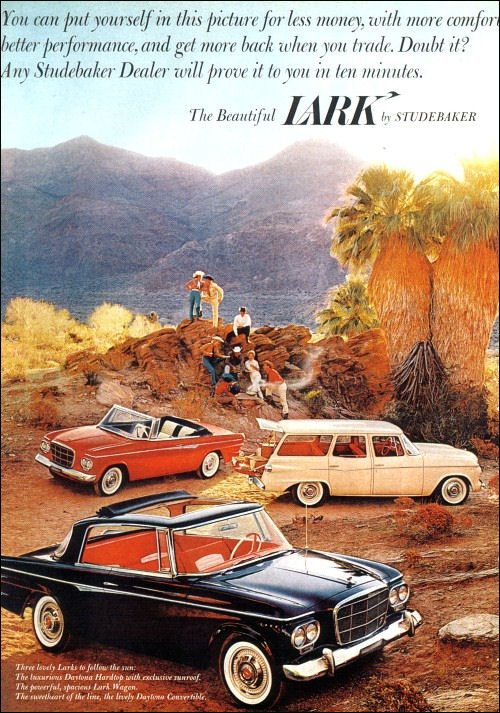

These cars were the first in the industry to be “facelifted” with plastic parts. The housing for the new dual headlights and the complete fins were fibreglass parts grafted on Studebaker bodies. There was very little chrome on the low front clip. Designer Duncan McCrae managed to include the 1956 Clipper tail lights for one last time, this time in a fin, and under a canted fin. A bizarre combination and poorly executed. Dodge did something similar, however the effect was less jarring. Added with the pods for the dual headlights and the new 1958 Packard was a real hodgepodge of late-1950s styling cues. The public reaction was predictable and though there were more models in the Packard lineup, sales were almost non-existent. Had Studebaker’s been built in Detroit on a Packard chassis, the outcome might have been positive. The Studebaker factory was older than Packard’s Detroit plant, with higher production requirements, which added to dipping sales. The company had problems and a new compact car, the Lark, was only a year away. All 1958 Packards were given 14 in (36 cm) wheels to lower the profile.

Predictably, some Packard devotees were disappointed by the marque‘s loss of exclusivity and what they perceived as a reduction in quality. They joined competitors and media critics in christening the new models as Packardbakers. They failed to sell in sufficient numbers to keep the marque afloat. However, with the market flooded by inexpensive cars, none of the minor automakers were able to sell vehicles at loss leader prices to keep up with Ford and GM. There was also a general decline in demand for large cars which heralded an industry switch to compact cars like the Studebaker Lark. Several makes were discontinued around this timeframe. Not since the 1930s had so many makes disappeared: Packard, Edsel, Hudson, Nash, DeSoto, and Kaiser.

Concept Packards

During the 1950s, a number of “dream cars” were built by Packard in an attempt to keep the marque alive in the imaginations of the American car-buying public. Included in this category are the 1952 Pan American that led to the production Caribbean and the Panther (also known as Daytona), based on a 1954 platform. Shortly after the introduction of the Caribbean, Packard showed a prototype hardtop called the Balboa. It featured a reverse slant rear window that could be lowered for ventilation, a feature introduced in a production car by Mercury in 1957 and still in production in 1966. The Request was based on the 1955 Four Hundred hardtop, but featured a classic upright Packard fluted grille reminiscent of the prewar models. In addition, the 1957 engineering mule “Black Bess” was built to test new features for a future car. This car had a resemblance to the 1958 Edsel. It featured Packard’s return to a vertical grill. This grill was very narrow with the familiar ox yoke shape that was characteristic for Packard, and with front fenders with dual headlights resembling Chrysler products from that era. The engineering mule Black Bess was destroyed by the company shortly after the Packard plant was shuttered. Of the ten Requests built only four were sold off the showroom floor. Richard A. Teague also designed the last Packard show car, the Predictor. This hardtop coupe’s design followed the lines of the planned 1957 cars. It had many unusual features, among them a roof section that opened either by opening a door or activating a switch, well ahead of later T-Tops. The car had seats that rotated out allowing the passenger easy access, a feature later used on some Chrysler products. The Predictor also had the opera windows, or portholes, found on concurrent Thunderbirds. Other novel ideas were overhead switches—these were in the production Avanti—and a dash design that followed the hood profile, centering dials in the center console area. This feature has only recently been used on production cars. The Predictor survives and is on display at the Studebaker National Museum section of the Center for History in South Bend, Indiana.

Astral

There was one very unusual prototype, the Studebaker-Packard Astral, made in 1957 and first unveiled at the South Bend Art Centre on January 12, 1958 and then at the March 1958 Geneva Motor Show. It had a single gyroscopic balanced wheel and the publicity data suggested it could be nuclear powered or have what the designers described as an ionic engine. No working prototype was ever made nor was it likely that one was ever intended.

The Astral was designed by Edward E Herrmann, Studebaker-Packards director of interior design, as a project to give his team experience in working with glass reinforced plastic. It was put on show at various Studebaker dealerships before being put into storage. Rediscovered 30 years later, the car was restored and put on display by the Studebaker museum.

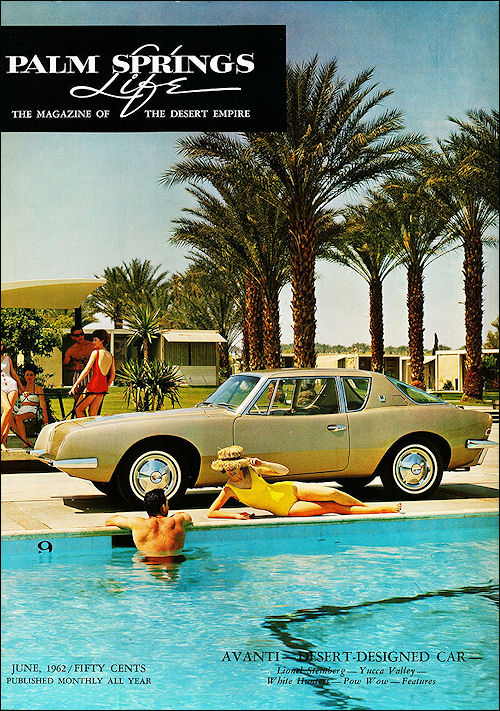

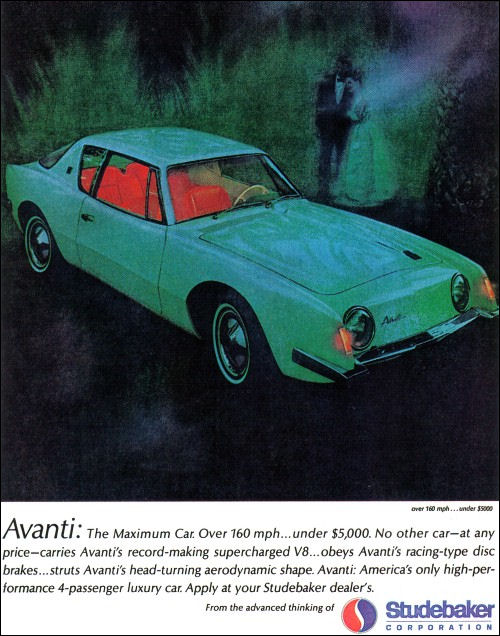

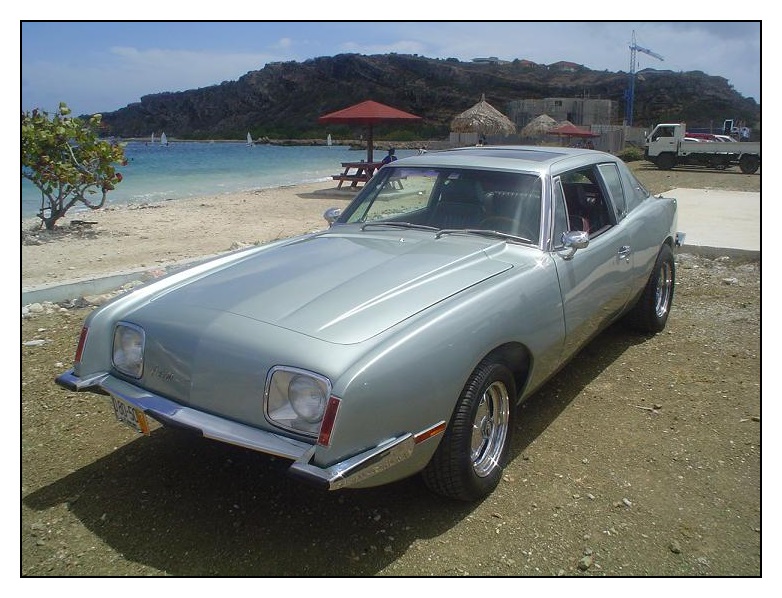

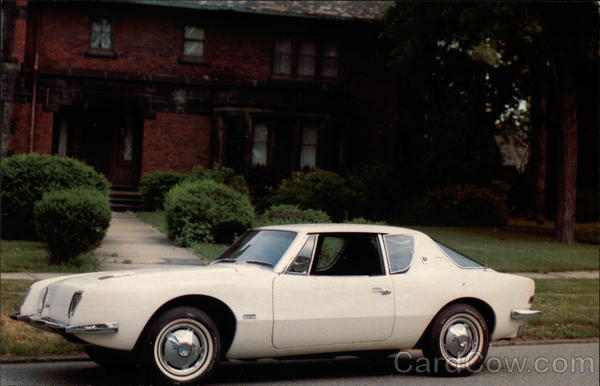

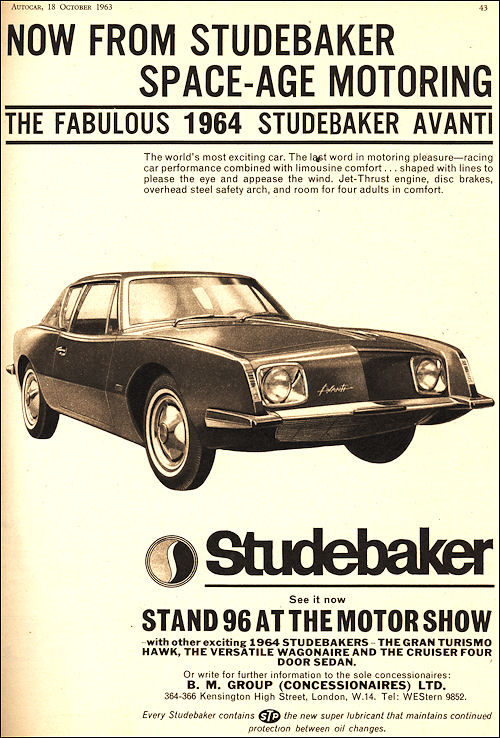

The end

Studebaker-Packard pulled the Packard nameplate from the marketplace in 1959. It kept its name until 1962 when “Packard” was dropped off the corporation’s name at a time when it was introducing the all new Avanti, and a less anachronistic image was being sought, thus finishing the story of the great American Packard marque. Ironically, it was considered that the Packard name might be used for the new fiberglass sports car, as well as Pierce-Arrow, the make Studebaker controlled in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

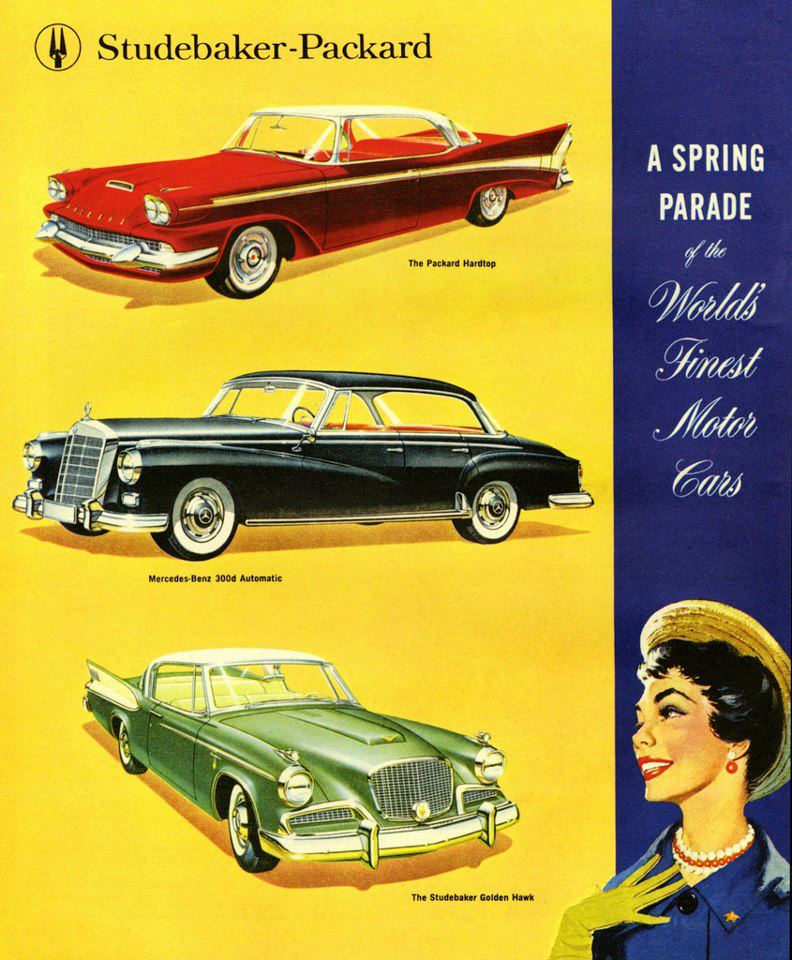

In the late 1950s, Studebaker-Packard was approached by enthusiasts to rebadge the French car maker Facel-Vega‘s Excellence suicide door, 4-door hardtop as a ‘Packard’ for sale in North America, using stock Packard V8s, and identifying trim including red hexagon wheel covers, cormorant hood ornament, and classic vertical ox yoke grille. The proposition was rejected when Daimler-Benz threatened to pull out of its 1957 marketing and distribution agreement, which would have cost Studebaker-Packard more in revenue than they could have made from the badge-engineered Packard. Daimler-Benz had little of its own dealer network at the time and used this agreement to enter and become more established in the American market thru SPC’s dealer network, and felt this car was a threat to their models. By acquiescing, SPC did themselves no favors and may have accelerated their exit from automobiles, and Mercedes-Benz protecting their own turf, helped ensure their future.

The revival

In the 1990s, Roy Gullickson revived the Packard nameplate by buying the trademark and building a prototype Packard Twelve for the 1999 model year. His goal was to produce 2,000 of them per year, but lack of investment funds stalled that plan indefinitely and the Twelve was sold at an auto auction in Plymouth, MI in July 2014.

Packard automobile engines

Packard’s engineering staff designed and built excellent, reliable engines. Packard offered a 12-cylinder engine—the “Twin Six”—as well as a low-compression straight eight, but never a 16-cylinder engine. After WWII, Packard continued with their successful straight-eight-cylinder flathead engines. While as fast as the new GM and Chrysler OHV V8s, they were perceived as obsolete by buyers. By waiting until 1955, Packard was almost the last U.S. automaker to introduce a high-compression V8 engine. The design was physically large and entirely conventional, copying many of the first generation Cadillac, Oldsmobile, and Studebaker Kettering features. It was produced in 320 cu in (5.2 L) and 352 cu in (5.8 L) displacements. The Caribbean version had two 4-barrel carburetors and produced 275 hp (205 kW). For 1956, a 374 cu in (6.1 L) version was used in the senior cars and the Caribbean 2×4-barrel produced 305 hp (227 kW).

In-house designed and built, their “Ultramatic” automatic transmission featured a lockup torque converter with two speeds. The early Ultramatics normally operated only in “high” with “low” having to be selected manually. Beginning with late 1954, the transmission could be set to operate only in “high” or to start in “low” and automatically shift into “high”. Packard’s last major development was the Bill Allison-invented “Torsion-Level” suspension, an electronically controlled four-wheel torsion-bar suspension that balanced the car’s height front to rear and side to side, having electric motors to compensate each spring independently. Contemporary American competitors had serious difficulties with this suspension concept, trying to accomplish the same with air-bag springs before dropping the idea.

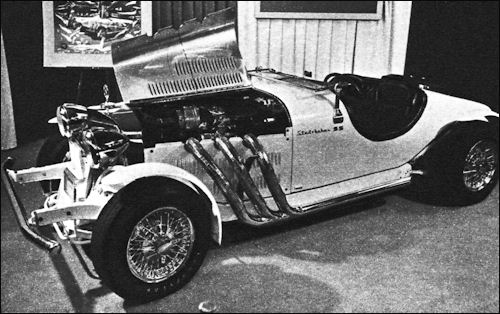

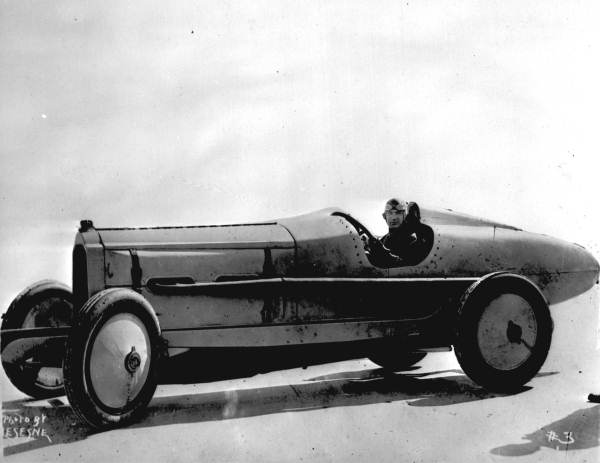

Packard also made large aeronautical and marine engines. Chief engineer Jesse G. Vincent developed a V12 airplane engine called the “Liberty engine” that was used widely in entente air corps during World War I. Packard powered boats and airplanes set several records during the 1920s. For Packard’s production of military and navy engines, see the Merlin engine and PT Boats which contributed to the Allied victory in World War II. Packard also developed a jet propulsion engine for the US Air Force, one of the reasons for the Curtiss-Wright take-over in 1956, as they wanted to sell their own jet.

Packard automobile models

- Packard Single-Cylinder models:

- Packard Twin-Cylinder model:

- Packard Four-Cylinder models:

- Packard Six-Cylinder models:

- Postwar Packards (including Clipper)

Packard show cars

Packard tradenames

- Ultramatic, Packard’s self-developed automatic transmission (1949–1953; Gear-Start Ultramatic 1954, Twin Ultramatic 1955-1956)

- Thunderbolt, a line of Packard Straight Eights after WW2

- Torsion Level Ride, Packard’s torsion bar suspension with integrated levelizer (1955–1956)

- Easamatic, Packard’s name for the Bendix TreadleVac power brakes available after 1952.

- Electromatic, Packard’s name for its electrically controlled, vacuum operated automatic clutch.

- Twin Traction, Packard’s optional limited-slip rear axle; the first on a production car worldwide (1956–1958)

- Touch Button, Packard’s electric panel to control 1956 win Ultramatic

The Packard advertising song on television had the words: Ride ride ride ride ride along in your Packard, in your Packard. In a Packard you’ve got the world on a string. In a Packard car you feel like a king. Ride ride ride ride ride along in your Packard, what fun! And ask the man, just ask the man the lucky man who owns one!

Legacy

America’s Packard Museum and the Fort Lauderdale Antique Car Museum hold collections of Packard automobiles. There are also collections in Whangarei and Maungatapere, New Zealand which were started by the late Graeme Craw.

See also

kampfflugzeugmotor-packard-v-1650-7-weiterentwicklung-unter-lizenz-des-rolls-royce-merlin-v12-zylinder-in-dieser-version-1315-bhp1

packard-bentley-42-litre

packard-custom-super-8-clipper-one-eighty

packard-darrin-victoria

packard-dominant-rutherford-v6-car

packard-eight-sport-phaeton

packard-flower-car

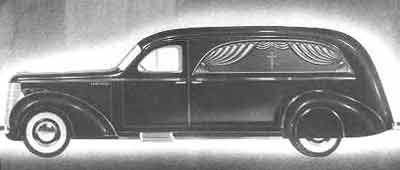

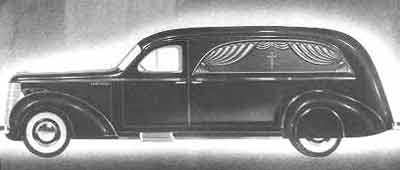

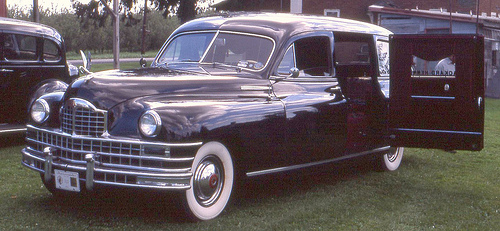

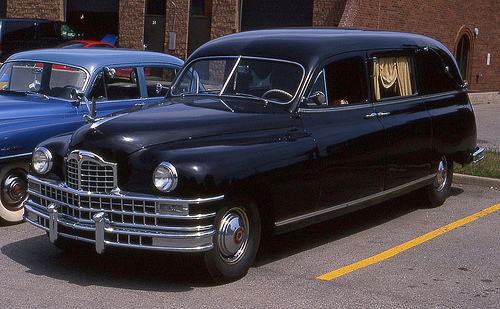

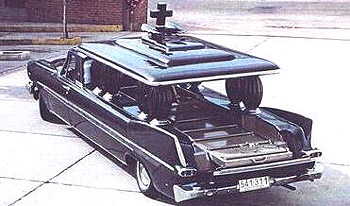

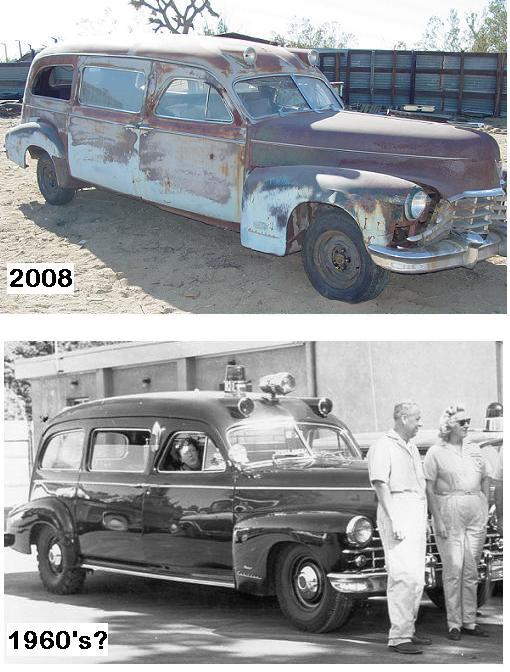

packard-hearse

Packard Hearse

packard-macauley-sportster-prototype

packard-one-twenty

packard-patrician

packard-predictor-snm

packard-six-convirtible-coupe

packard-super-8-2232-convertible-victoria-coupe

packard-tow-truck

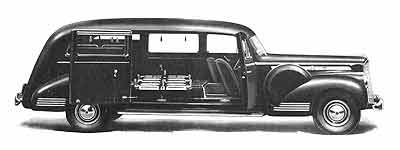

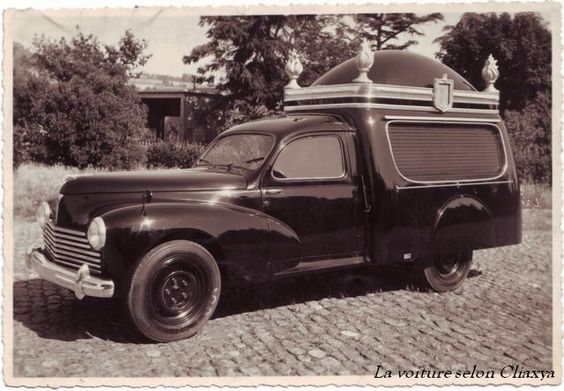

Packard Hearses and Flowercars

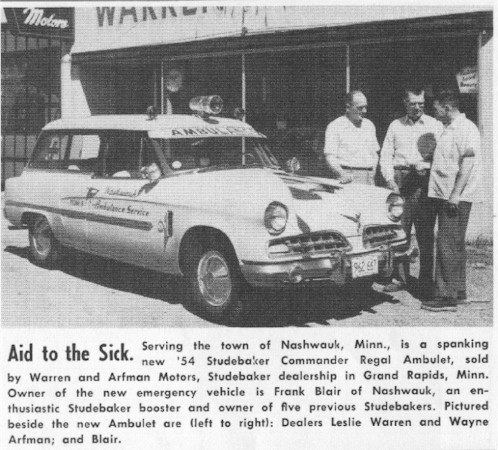

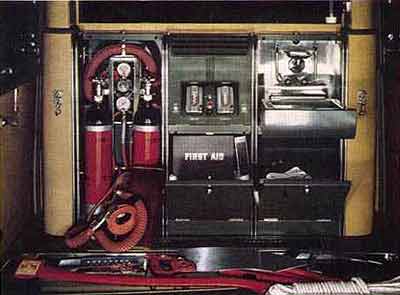

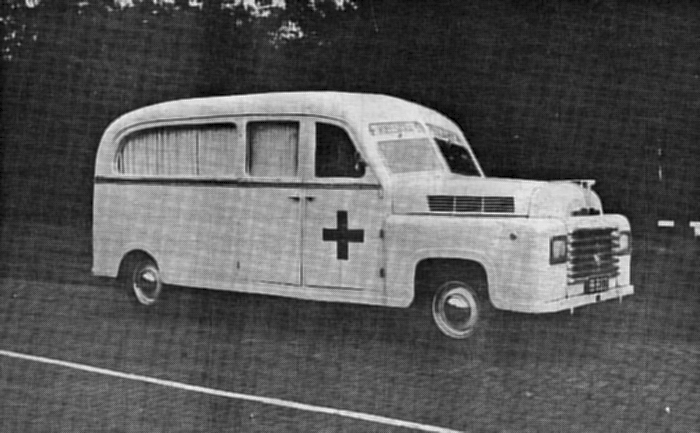

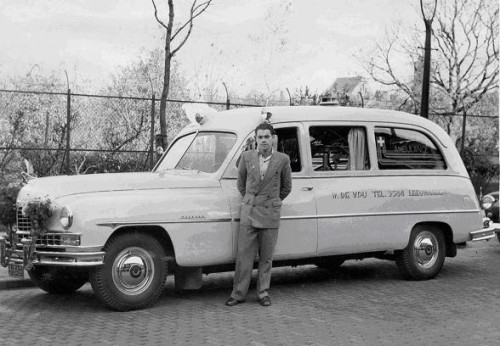

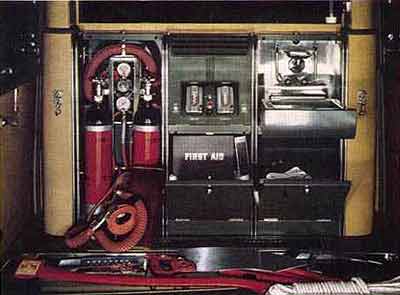

Ambulances

That was it

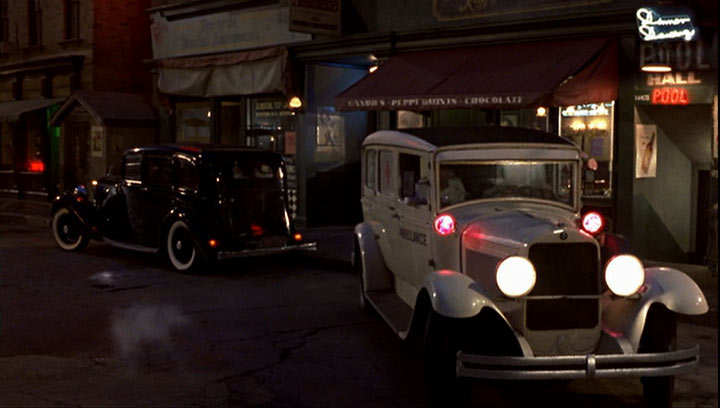

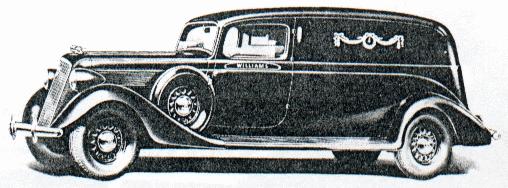

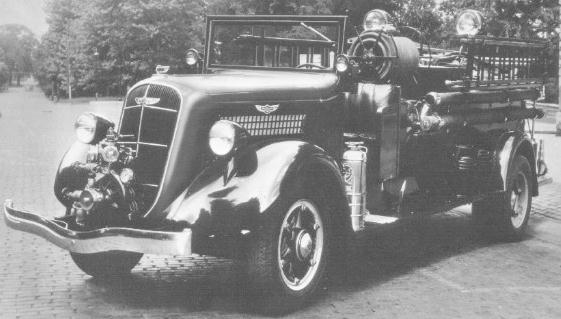

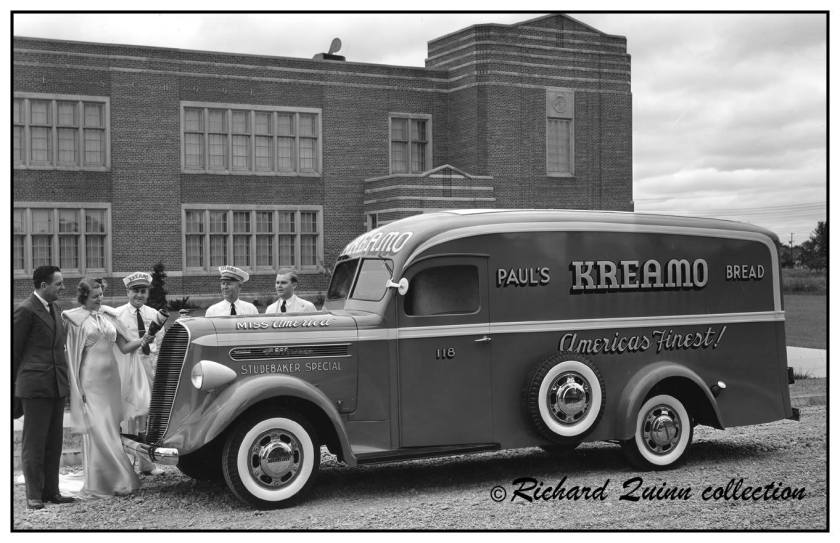

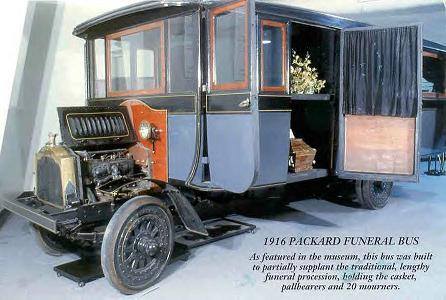

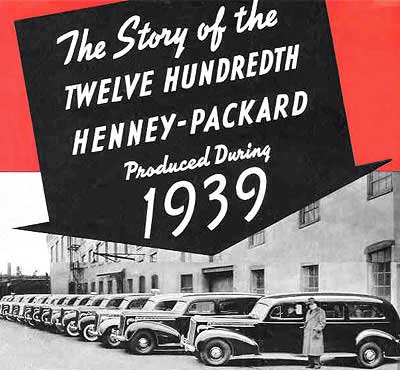

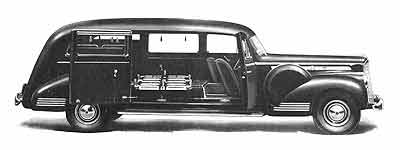

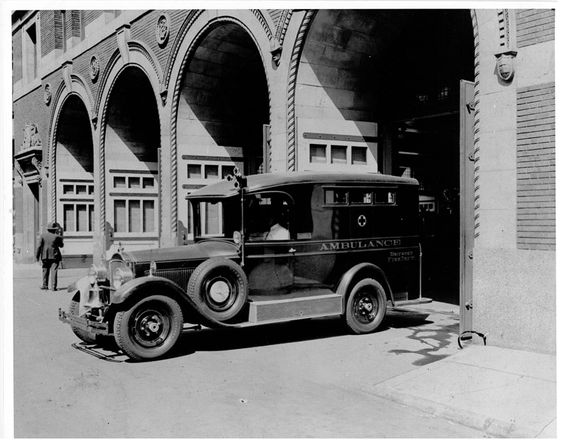

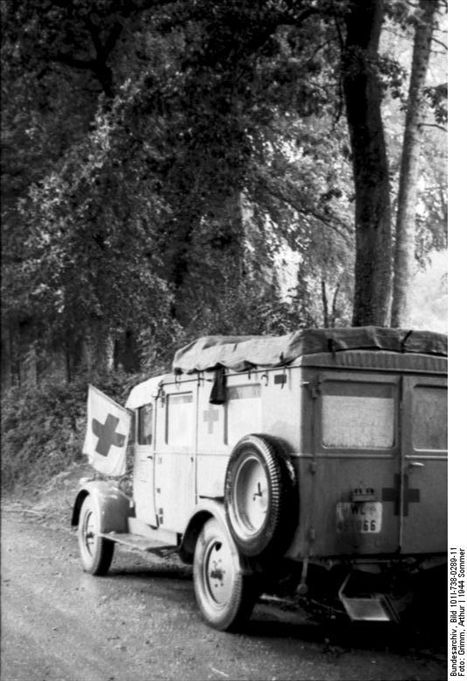

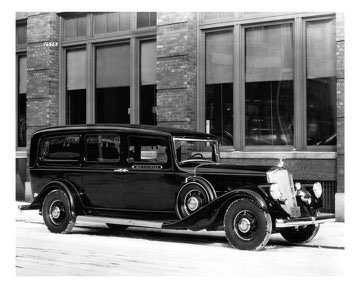

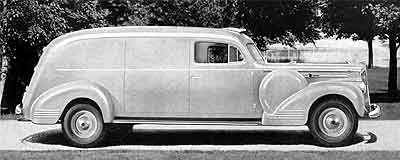

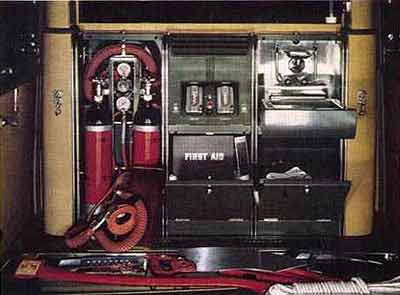

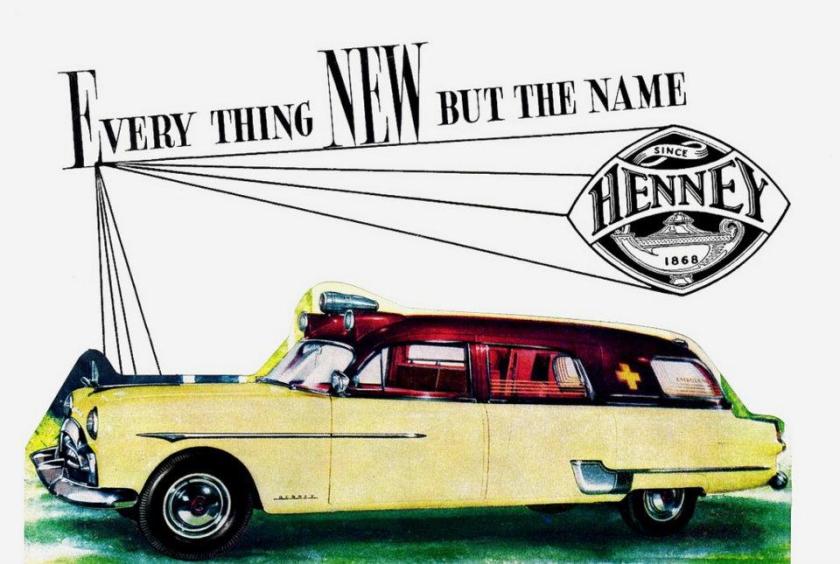

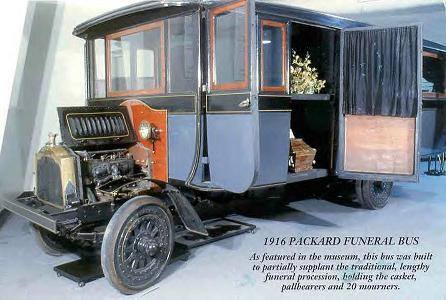

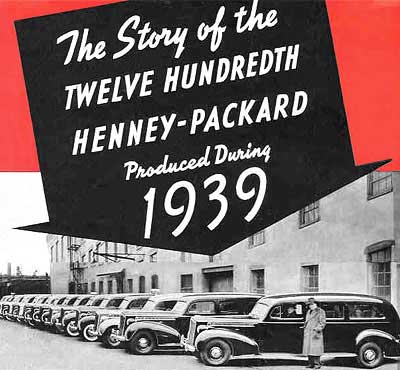

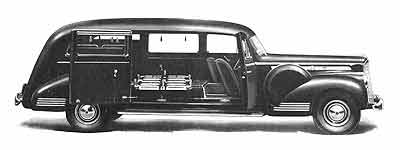

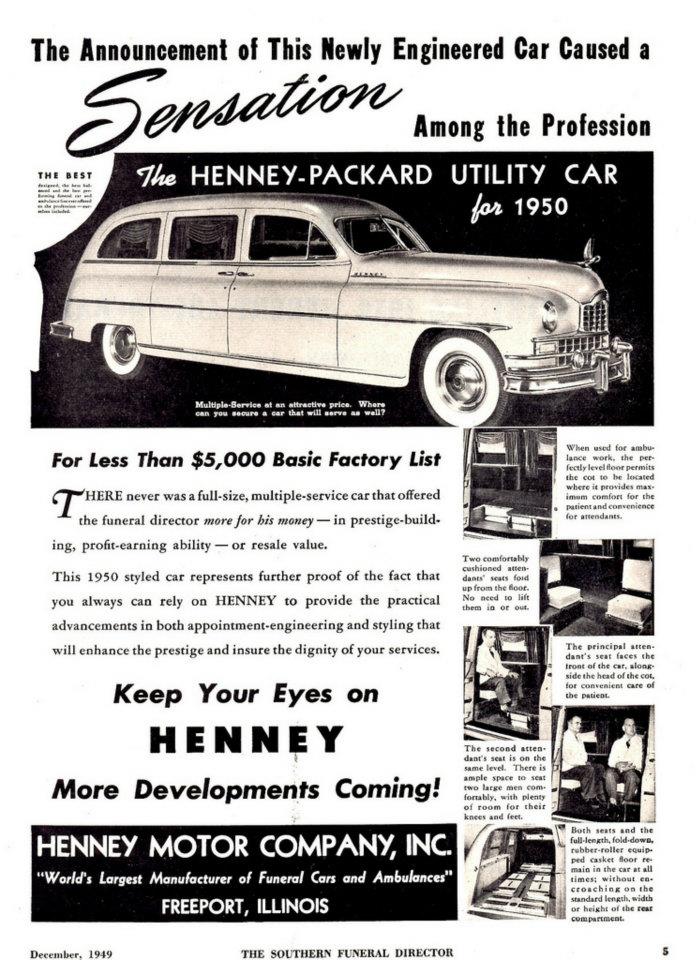

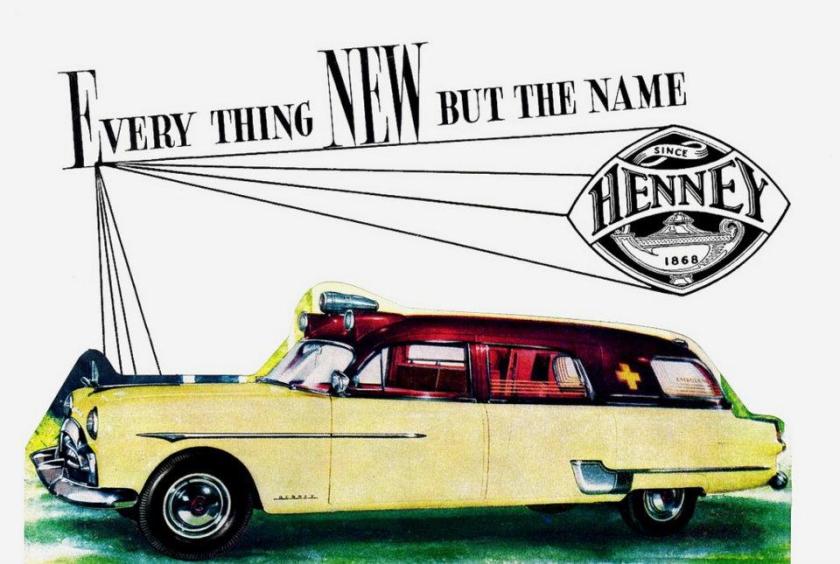

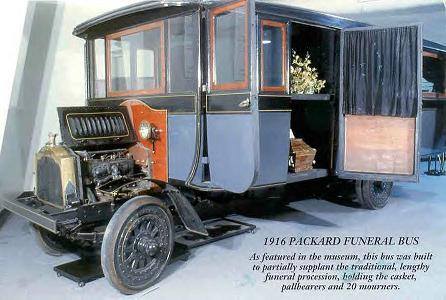

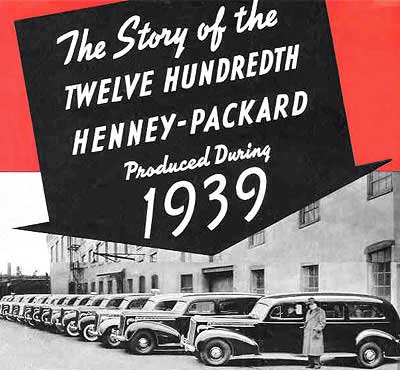

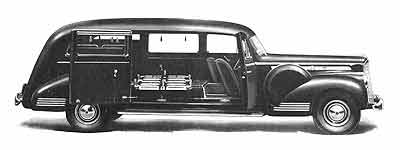

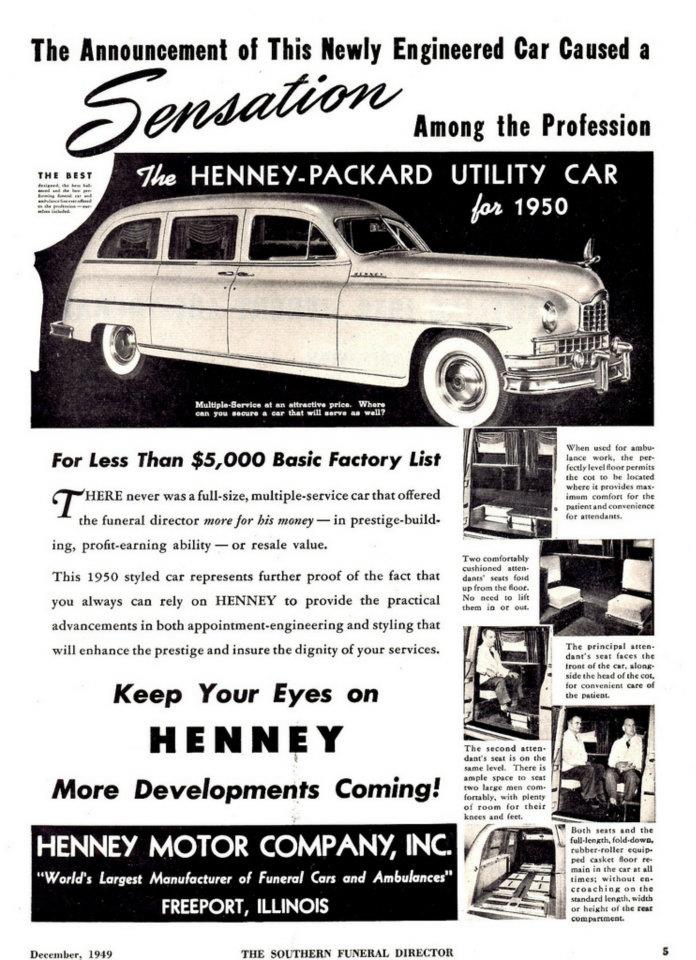

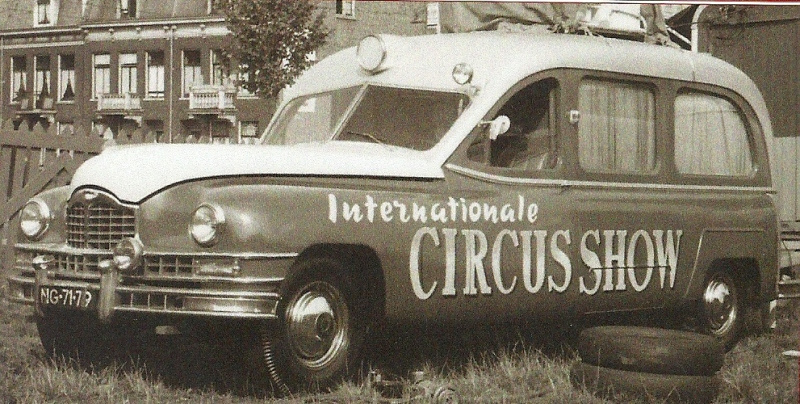

Packard – Ambulances – Flowercars – Hearses -mostly by Henney coachbuilders from 1916 till 1958 when Packard fuseerde met Studebaker.

Packard – Ambulances – Flowercars – Hearses -mostly by Henney coachbuilders from 1916 till 1958 when Packard fuseerde met Studebaker.

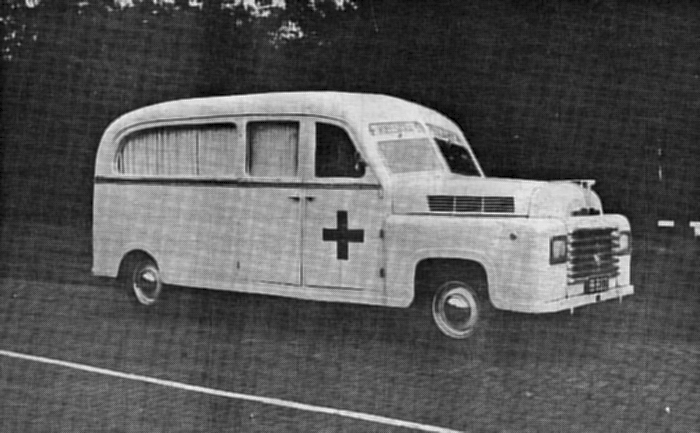

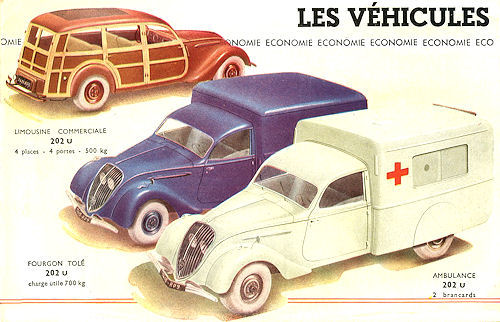

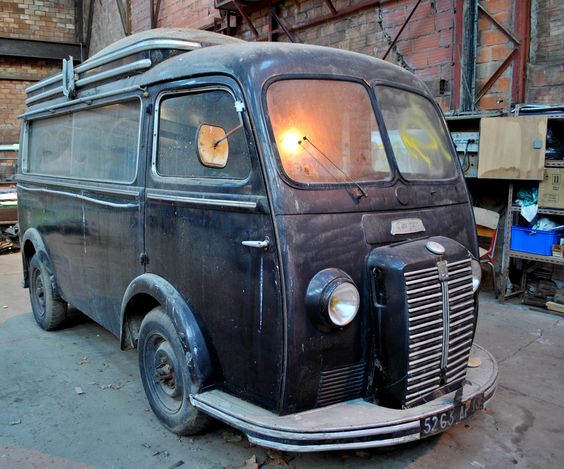

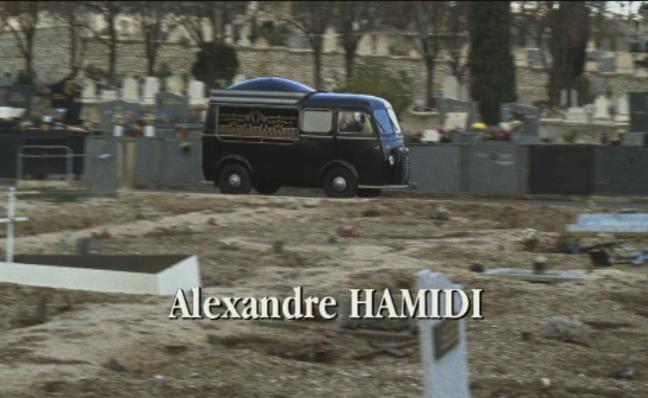

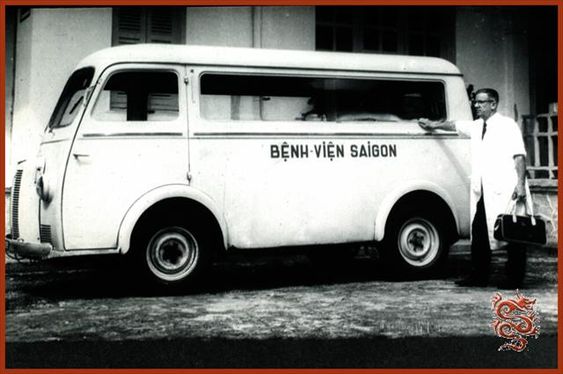

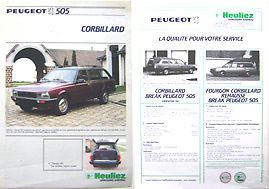

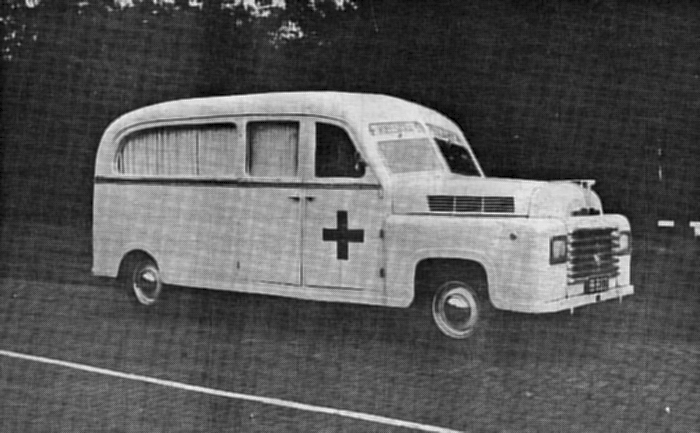

Peugeot Ambulances and Hearses from 1934 till recent

Peugeot Ambulances and Hearses from 1934 till recent

Phänomen krankenwagen – ambulances

Phänomen krankenwagen – ambulances

Pierce-Arrow Ambulances and Hearses

Pierce-Arrow Ambulances and Hearses

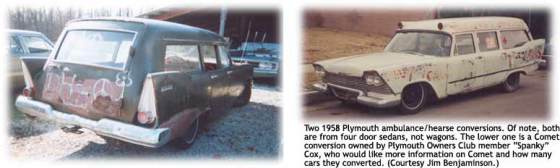

Plymouth Ambulances and Hearses

Plymouth Ambulances and Hearses

Porsche Ambulances of fast resque and Hearses

Porsche Ambulances of fast resque and Hearses

Polski Fiat Ambulances

Polski Fiat Ambulances

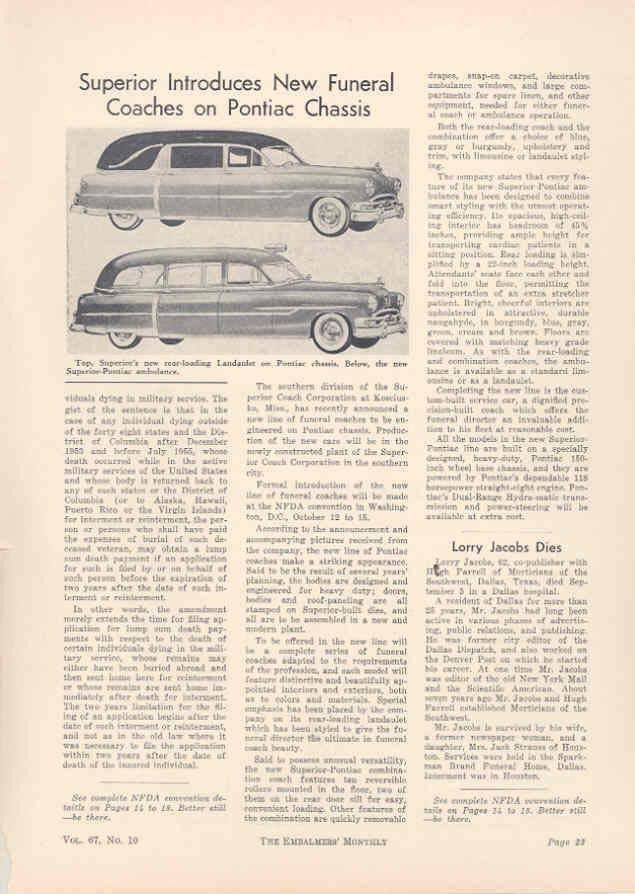

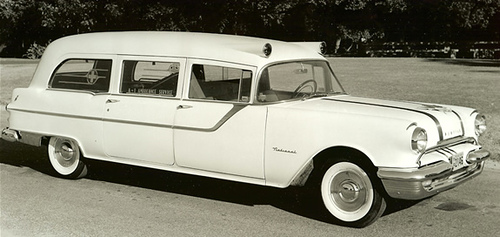

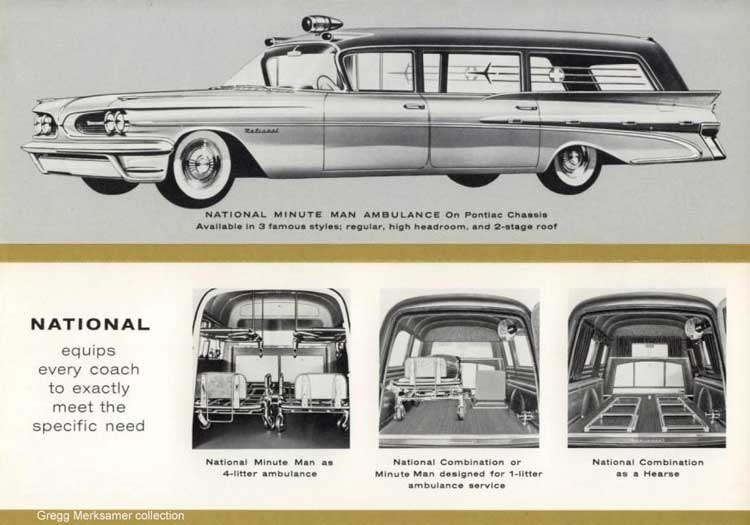

PONTIAC Ambulances + Hearses

PONTIAC Ambulances + Hearses

1909 De Spyker ambulances voor het Roode Kruis

1909 De Spyker ambulances voor het Roode Kruis 1909 SPIJKER Ambulance amsterdam redcross lehmann trompenburg

1909 SPIJKER Ambulance amsterdam redcross lehmann trompenburg

1914 Spyker

1914 Spyker

1916 ford-t-ambulances-st-vincents-web

1916 ford-t-ambulances-st-vincents-web

1918 Ford T Ambulance

1918 Ford T Ambulance

1920 Dodge Brothers model 30 Ambulance Zuid Holland Wateringen H-31364

1920 Dodge Brothers model 30 Ambulance Zuid Holland Wateringen H-31364

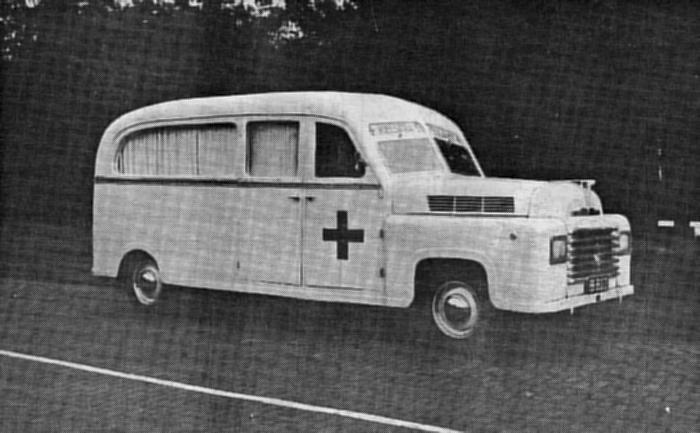

1939 Packard Ziekenauto op Storkterrein Hengelo NL

1939 Packard Ziekenauto op Storkterrein Hengelo NL

1940 Ziekenauto Bedrijfsongeval Demka fabrieken te Zuilen NL

1940 Ziekenauto Bedrijfsongeval Demka fabrieken te Zuilen NL

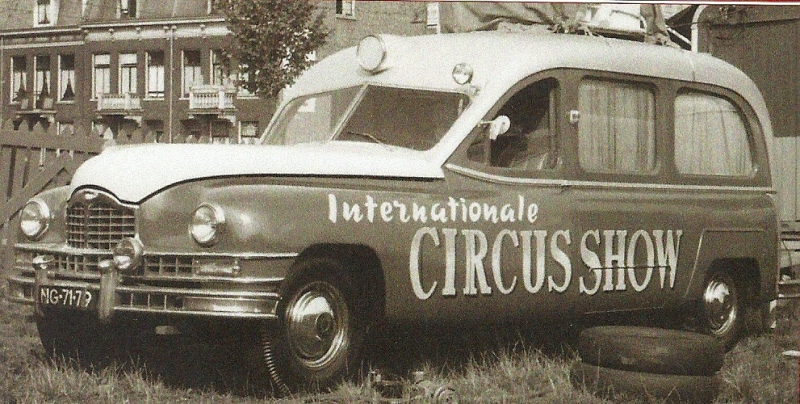

1947 Ziekenauto uit Sneek Chauffeur was T.J Vallinga. met Packard uit 1947

1947 Ziekenauto uit Sneek Chauffeur was T.J Vallinga. met Packard uit 1947

1950 Packard 1950 Buick en Buick De Vrij Zuiderplein Lw NL

1950 Packard 1950 Buick en Buick De Vrij Zuiderplein Lw NL

Cadillac Ambulance

Cadillac Ambulance

1965 Peugeot D4B Ambulance gemeente Texel

1965 Peugeot D4B Ambulance gemeente Texel

1967 Citroën ID 19 Ambulance NL

1967 Citroën ID 19 Ambulance NL

1967-68 Mercedes Benz 230 amb 84-91-FM

1967-68 Mercedes Benz 230 amb 84-91-FM

1969 Citroën hy-ambulance NL

1969 Citroën hy-ambulance NL 1968 Mercedes-Benz ambulance Visser, Leeuwarden ZS-97-16

1968 Mercedes-Benz ambulance Visser, Leeuwarden ZS-97-16 1969 20-93-JM MERCEDES-BENZ W114 230 BINZ Ambulance NL

1969 20-93-JM MERCEDES-BENZ W114 230 BINZ Ambulance NL

1971 Merc Benz 220

1971 Merc Benz 220 1970 Bedford Ambulance HY-91-JT NL

1970 Bedford Ambulance HY-91-JT NL

1971 peugeot-j7-ambulance-carrosserie-visser-standplaats-schiphol NL

1971 peugeot-j7-ambulance-carrosserie-visser-standplaats-schiphol NL

1979 Peugeot 504 Ambulance NL

1979 Peugeot 504 Ambulance NL 1980 Mercedes-Benz 240D NL

1980 Mercedes-Benz 240D NL

1985 PEUGEOT 505 GR Ambulance NL

1985 PEUGEOT 505 GR Ambulance NL 1986 Opel Senator Miesen Ambulance D

1986 Opel Senator Miesen Ambulance D 1987 Peugeot J9 ambulance Leiden en omstreken RP-44-XJ NL

1987 Peugeot J9 ambulance Leiden en omstreken RP-44-XJ NL

1989 Mercedes-Benz W124 XY-96-JS Binz carr NL

1989 Mercedes-Benz W124 XY-96-JS Binz carr NL

2001 Nederlandse Volvo S80 ambulance met Nilson carrosserie NL

2001 Nederlandse Volvo S80 ambulance met Nilson carrosserie NL

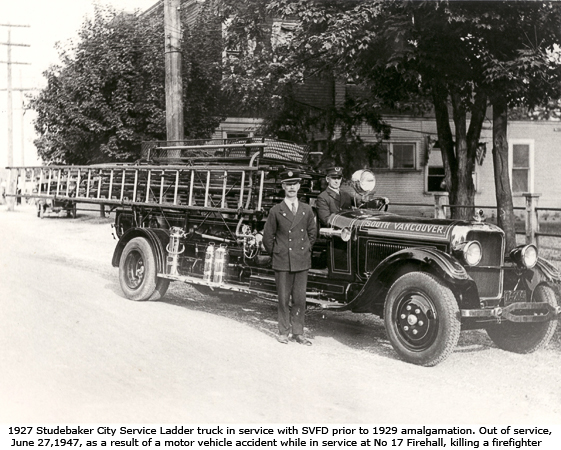

![1929 Studebaker Commander Superior Samaritan [FD]](https://myntransportblog.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/1929-studebaker-commander-superior-samaritan-fd.jpg?w=840)